The 1890s: Winds of Change

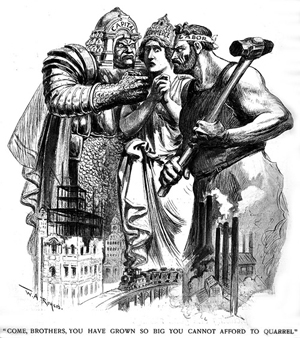

The Progressive Era, which began in 1890 and lasted until about 1913, spawned fundamental social and political changes that transformed the character of post-Civil War America. Agriculture, industry, and transportation all rushed to meet the evolving needs of the nation although these three entities often found themselves at odds with one another. Many Horatio Alger-esque, "common" men–farmers and industrial laborers in particular–feared that no matter how hard they worked, big business would prevent them from significantly bettering their lots. Historian Howard Zinn summarizes the conflict thus: "Labor struggles could make things better, but the country's resources remained in the hands of powerful corporations whose motive was profit, whose power commanded the government of the United States." [1]

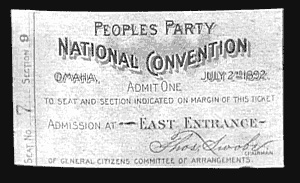

In direct response to this imbalance, the Populist school of thought, also known as the People's Party, came into existence during the latter 1800s. This political phenomenon, remarkably, remains still today the largest democratic uprising in American history. The speed at which the movement built and the considerable political distance it traversed testifies to the intense desire of many Progressive Americans for the change they saw as essential to their very survival. Many factors contributed to the evolution of the Populist movement, including the rise of industrialization, the suspicion of alliances between corporations and government, Westward migration, and even adverse weather patterns. The match that sparked this combination of factors into social and political action, however, was the desperate poverty of the South after the Civil War.

Walt Whitman once wrote that the Civil War would change the "essence of history, philosophy, art, poetry, and even personal character 'for all future America'." [2] As if in agreement, decades after Whitman's death a historian concurred, "People understood that the war–the Civil War–had changed everything." [3] One of the most immediate changes in people's lives after the war was that the economics of daily survival had become considerably more complicated. This was especially true in the South, where ruin and poverty had assumed massive proportions. Southern economic suffering would drive many former Confederates to chalking the letters "G.T.T." on their front doors and leave overnight: "gone to Texas." The exodus out of the war-torn Southern states swelled every year until during the 1870s, nearly 100,000 departed for new lands and opportunities in the southwestern state. [4]

In September 1877, after years of decreasing rainfall and economic humiliation under the unavoidable "crop lien system," a small group of farmers formed a society called the "Knights of Reliance." The members' objective was to educate themselves against the time when "all the balance of labor's products . . . concentrated into the hands of a few, there to constitute a power that would enslave posterity." [5] This group would later rename itself "The Farmer's Alliance," the precursor to the People's Party.

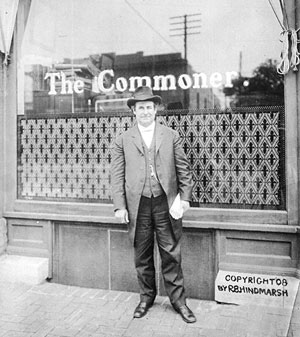

The Alliance spent nine years trying to improve crop production techniques and then, having had no success, shifted its focus to political activation. Ultimately, Populists wanted to enact legislative change and "claim respect not given them by the nation's powerful industrial and political leaders." [6] They advocated the nationalization of railroads and communication systems, reform of the monetary system, change in electoral practices, and an end of subsidies to private corporations. They also chose a presidential nominee, William Jennings Bryan, who famously delivered his acclaimed "Cross of Gold" speech in favor of Populist goals at the 1896 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. That year John Graves echoed Bryan's beliefs in the Atlanta Constitution: "I say it fearlessly, and it can not be denied, the reform for which the masses have been clamoring for years . . . has never been written, and might never have been written . . . until the Populist Party, 1,800,000 strong, thundered in the ears of Democratic leaders the announcement that a mighty multitude demanded these reforms." [7] Peattie once wrote of Bryan, having been introduced to him at a dinner party, "He looks like a Roman emperor. He has the right kind of head for carving on a coin." [8]

Bryan lost the election to William McKinley, but the goals of the People's Party were not erased from America's political consciousness. Some Populist beliefs would survive to become legislation during later administrations. In 1912 at the goading of Progressive Democrat Franklin Roosevelt, the direct election of U.S. senators became law by constitutional amendment. Theodore Roosevelt also fulfilled Populist's goals when he expanded the federal regulation of private sector businesses, established the WPA's employment programs, and increased aid to troubled farmers. [9]

Peattie actively supported the Populist movement and wrote often in its defense. She helped a friend, a social activist by the name of T.H. Tibbles, write a short novel about a Populist utopia, titled The American Peasant: A Timely Allegory. She also campaigned for William Jennings Bryan. "The West was hard-pressed at that time," Peattie once wrote. "Railroads and Eastern investors were milking the hard-working and inexperienced West and causing hardships." [10]

Peattie saw firsthand the dire situation facing the agriculturalists. Her city, which had just a few years before been called "The Wonder City of the West" and boasted an economy with aggregate sales of $50.2 million, [11] was losing its population fast. Nearly thirty thousand left the Omaha area in the early 1890s, half the amount that had immigrated thereto during the decade before.

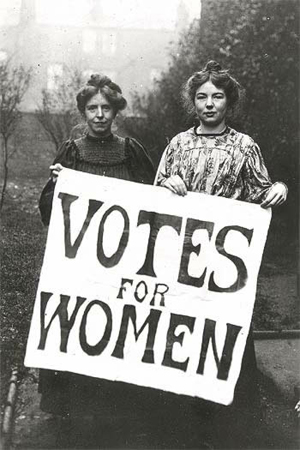

At the same time, women were struggling to level both the economic and social playing fields by pursuing political equality. "Woman suffrage" was a major concern of the era, as were the educational, occupational, and personal freedoms available to women. One lady, settled in the West, wrote in her journal that if women can care for their families, "train them morally and bear a share of their school education, then why cannot she grasp the governmental questions as well and bring to hear her experience and intuition?" [12]

Suffrage, which received increased attention after black men were granted the vote in 1867, proved to be a difficult, lengthy battle. Universal suffrage was inherently inaccessible because women themselves had to persuade the male electorate to grant them the right to vote. In keeping with Victorian tradition, many men believed that women were not suited "by circumstance or temperament for the vote." [13] Writes an historian, "Western political philosophers insisted that a voter had to be independent, unswayed by appeals from employers, landlords, or an educated elite. Women by nature were believed to be dependent on men and subordinate to them. Many thought women could not be trusted to exercise the independence of thought necessary for choosing political leaders responsibly." [14] Women were also thought of as workers within the home; to grant them liberties might mean the "disruption of the family." [15]

Universal suffrage was achieved in 1920, as ratified in the Nineteenth Amendment. However, historian Julie Roy Jeffrey points out, "political emancipation does not necessarily mean sexual or social emancipation." [16] Women still faced a long road in the struggle for equal opportunities and equal treatment.

As the decade unfolded, Peattie's column grew in popularity. She received fan mail from across the country in response to her keen editorial observations and wit. "My writings began to bring responses from many sources-men in penitentiaries, on lonely ranches, women in convents, distinguished people in the East, cultivated people over the state. I had a sense of eating life and no matter how much I had, I was still unsatisfied. To write about it all was the most intense satisfaction." [17]

The 1890s: Winds of Change

- Laboring for the Cause of Women's Rights

- William Jennings Bryan and The Cross of Gold

- The Removal of Queen Liliuokalani

References

Armitage, Susan, and Jameson, Elizabeth. The Women's West. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

"Digital History: The Progressive Era." http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/modules/progressivism/index.cfm.

"History of Women's Sufferage." Groilers Encylopaedia Americana. http://teacher.scholastic.com/activities/suffrage/history.htm.

Goodwyn, Lawrence. The Populist Moment. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976.

"History of Women's Sufferage." Groilers Encylopaedia Americana. http://teacher.scholastic.com/activities/suffrage/history.htm

Larsen, Lawrence, and Cottrell, Barbara. The Gate City: A History of Omaha. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

Myres, Sandra L. Westering Women and the Frontier Experience: 1800-1915. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1982.

Peattie, Elia. The Star Wagon. Edited and Anotated by Joan Stevenson Falcone.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harperperennial, 2003.

Illustrations

"The Quarrel of Labor and Capital." Southern Labor Archives: http://www.library.gsu.edu/spcoll/spcollimages/labor/19clabor/Labor%20Prints/79-40_11.jpg. Courtesy Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University.

"Populist ticket." Nebraska Studies.org: "Roots of Progressivism:" http://www.nebraskastudies.org/ (Permission pending.)

"Votes for women." http://www.nwhm.org/images/votesforwomen.jpg. Public Domain.

"William Jennings Bryan in front of The Commoner in Lincoln." http://www.nebraskastudies.org/. Source —Nebraska State Historical Society, RG17621. (Permission pending.)

Notes

XML: ep.owh.pol.0001.xml