The Star Wagon: The Memoirs of Elia Wilkinson Peattie

Edited and Annotated by Dr. Joan Stevenson Falcone, Illinois State University

Epigraph

Hitch your wagon to a star.Let us not fag in paltry works which serve our pot

and bag alone....Work rather for those interests

which the divinities honor and promote,-

justice, love, freedom, knowledge, utility.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1899 Society & Solitude

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to a number of people who have inspired me, both professionally and personally, through the long, arduous process of editing and annotating this manuscript: the grandsons of Elia and Robert Peattie—Mark and Noel Peattie, for lending the manuscript and family papers, for reading my work and offering critical commentary, and Michael Peattie for lending family photographs and sharing his memories; Alice, David, Caroline, and Peggy Peattie, Dr. Sidney H. Bremer, Dr. Robert Bray, Dr. Ray Lewis White, Betty Doubleday Frost, Bruce Bennett, Vonda Krahn, Dittie Widdicombe, Marilee Shore, Margaret "Mimi" Bartol Pospisil, Christopher Bartol, Andrew Haynes, Tony Roman, the Newberry Library, the Lanier Library, the Chicago Tribune, Max, Pompie, and my husband, Dr. David Nicholas Falcone. Thank you.

Dedication

This work is dedicated to my husband. David, thank you for your support, guidance, and love.

Joanie

Preface

My initial discovery of Elia Wilkinson Peattie came during my undergraduate days at Illinois Wesleyan University, but during my quest for a dissertation topic, as a graduate student in the Department of English at Illinois State University, I rediscovered her—she was, and remains, the “kindred spirit” for whom I had been searching. Since then my academic pursuits have taken me on an exciting journey. I have written about her, lectured about her, taught her works in my classes, and shared her manuscript with scholars throughout the United States. I have traveled from central Illinois to both the east and west coasts, and I have met, or corresponded with, many of her descendants, as well as children of her friends. Elia’s life-long goals, to raise her family out of poverty and to have them rise to cultural refinement, have been realized.

Peattie simplified my task of editing The Star Wagon because she was an excellent writer. I have retained her sometimes archaic word choices and spellings making minor changes of typographical errors; other changes made for clarification have been indicated by the customary use of brackets. Some information, that would have been of interest only to family, had to be cut from the original manuscript which in book form, would have been unwieldy. The chapter entitled “Barbara” was a separate chapter, apparently, written last; I have placed this chapter in what would have been her birth order, which is how the chapters of the Peattie sons were placed. I have inserted additional material, such as identification of family members and dates which I believe adds clarity and helps the reader to better follow the text. These changes have been noted in the manuscript using the customary documentation procedures of the Modern Language Association.

The real challenge came with the identification of the many people to whom she refers throughout the manuscript; as with all autobiographical writings, the famous and important are mingled with relatives, friends, and even a town drunk. I have attempted to identify the famous and, briefly, the not-so-famous through footnotes. Unless otherwise noted, the footnote information came from well-known reference sources, which, of course, do not require citation; for other sources, according to customary MLA procedure, I have provided an in-text citation and a works cited page. I have also furnished a list of suggested readings for those who would like to know more about Elia W. Peattie within the context of her own time.

My intentions are to present The Star Wagon as true to its original form as possible with little interruption of commentary or analysis; thus, aside from the footnoted information, and the changes made above, I have limited my comments to the introduction and included a time line to help the reader gain a better overall perspective of important events.

Interestingly, as The Star Wagon takes us back to the turn-of-the-twentieth century, we have, ourselves, embarked upon a new century, another milestone upon which women should pause and look ahead. Where do we want our female descendants to be in another century? in another millennium? Where will they be? History has shown us that we can best answer these questions by looking back from where we came. We have made much progress, but, unfortunately, many of the patriarchal issues with which Elia Wilkinson Peattie dealt remain unresolved.

Suggested Reading List

Bremer, Sidney H. Introduction. The Precipice. By Elia W. Peattie. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1989. ix-xxvi.

“Lost Continuities.” Soundings 64 (Spring 1981), 29-51.

“Willa Cather's Lost Chicago Sisters.” Women Writers and the City: Essay in Feminist Literary Criticism. Ed. Susan Merrill Squier. Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 1984. 210-29.

Bremer, Sidney H. and Joan Stevenson Falcone. “Peattie, Elia Amanda Wilkinson.” Women Building Chicago 1770-1990: A Biographical Dictionary. Eds. Rima Lunin Schultz and Adele Hast. 2001: Indiana UP.

Laughlin, Clara E. Just Folks. New York: Macmillan, 1910.

Morgan, Anna. My Chicago. Chicago: R. F. Seymour, c. 1918.

Raftery, Judith. “Chicago Settlement Women in Fact and Fiction: Hobart Chatfield Chatfield-Taylor, Clara Elizabeth Laughlin, and Elia Wilkinson Peattie Protray the New Woman.” Illinois Historical Journal 88 (1995): 37-58.

Welter, Barbara. Dimity Convictions: The American Woman in the Nineteenth Century. Athens: Ohio UP, 1976.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, as more and more works by women and about women have been interpreted by women, we have recognized our responsibility to consider women's autobiographical writings, particularly those writing at the turn of the twentieth century, because they are crucial to our understanding of the women who played a pivotal role in shaping women’s rights today. They also serve as a reminder that the twenty-first century finds us still struggling with some of the same issues, and that some rights are very much in jeopardy. While feminists have always been aware of the importance of women’s autobiographies, we still do not dominate the powerful positions that can cause them to be brought to the forefront—even at the university level where male department chairs vastly out number female department chairs. Thus we still struggle to convince the male powers who be that women’s fictional and autobiographical writings ought to play a prominent role in every area of the liberal arts tradition. It is my contention that, for a number of reasons, the work and writing of turn-of-the-twentieth-century women are greatly under-valued.

As feminist critics of women writers have determined, different critical categories have been applied to male and female writers. More often than not, males have been canonized, or at least anthologized as realists, while their female counterparts have been ignored, confirming yet again, “the power of patriarchy to render invisible that which it does not value” (Lane xi). Nowhere is this concept more vivid than in Chicago's turn-of-the-twentieth-century women writers. The critic Sidney H. Bremer has dubbed these women, in an article by the same name, “Willa Cather's Lost Chicago Sisters.” The group consists of Elia Peattie, Willa Cather, Clara Laughlin, Edith Wyatt, Clara Burnham, and Alice Gerstenberg. Bremer's thesis is essentially that women's Chicago novels present the city as part of a life experience that is continuous, embedded in natural forces and in communal ties and conflicts (212). While we have begun to recognize works by women which were previously labeled “regional realism” and even elevated them into anthologies along side male works of realism, we have not yet truly recognized the importance of Chicago's women writers.

Rather, as Bremer points out, we have allowed men to tell the story of Turn-of-the-Twentieth-Century Chicago (Intro xi). The Chicago we have come to know, and to teach, is the masculine city where raw industrial capitalism is the machine that devoured the poor, the amoral city that encroached upon the genteel elites surrounding them with everything that was unnatural (Falcone 71), and the wasteland Chicago where immigrants served as a “cog in the great packing machine” (Sinclair 29). Bremer notes that while these men, “outsiders,”—Henry Blake Fuller, Upton Sinclair, Theodore Dreiser, Hamlin Garland, Frank Norris, and Robert Herrick—have been chosen to represent Chicago, Henry Blake Fuller was the only native Chicagoan; all the others were merely passing through (Intro xi). While Robert Herrick established a residence there, he never became a part of the City; he merely “camped” there “loathing the urban monstrosity” (Aaron viii). Peattie seems to have sensed, too, that the “insider’s view” (Bremer xi) was missing when, in 1903, she said:

No book written about Chicago has ever satisfied me. Certainly poor Frank Norris’ book ‘The Pit,’ does not do so. We have such a fierce old devilfish of a city that it is next to impossible to capture it. [. . .] Suppose a writer gets a pretty firm hold of one tentacle, all the other tentacles wriggle away from him, and the captor can no more say ‘This is Chicago’ than the man who gets the severed paw of a bear in a trap can say ‘This is the bear’ (“Elia W. Peattie on ‘The Pit’” 13).

Bremer chides us for accepting the “outsider's vision” (Intro xi) and neglecting “in a single gendered package [. . .] the insider's view [. . .] (Intro xi) which is presented by these Chicago women writers who “as participants rather than observers” present a “vision of the city as an organic family” (Intro xii). Hugh Duncan makes an important point, too, when he points out that Chicago “women writers were influenced by having seen Chicago destroyed and rebuilt—all in twenty years” (8). They had lived the city from the devastation after the great fire to the Columbian Exposition.

But shouldn’t literature speak the universal truth about human existence? If so, then we need to see the complete story; we need to hear it from the women as well as men. Consider Chicago, for example. Why is men’s work more important than women's work? Why are the packing houses more valuable to study than the settlement houses? It is so because men have determined that it is so. Women’s work and settlement houses reveal far more universal themes—religious, cultural, social, political—than the slaughter houses ever did, and only a fraction of the city's population worked there. Moreover, issues that Chicago's women writers attempted to address, insight into female consciousness, patriarchy, economic dependence of women, gender differences in the work place, still affect over half of today's population.

While fictional works by women have been largely ignored despite the important contributions they make, their autobiographies have been ignored virtually all together. Susan Babbitt tells us that they “used to be considered something less than literature, not requiring the mastery of language required for fiction. But literary critics have since recognized that autobiography is itself the claiming and discovery of self, and that it is also about subjectivity, responsibility, freedom, and autonomy” (215). Only within the last couple of decades, because of critics like Martine Watson Brownley and Allison B. Kimmich, according to Babbitt (215), have these writings been considered any more than a “subliterary genre” that was quite unequal to fictional writings or even autobiographies by men (Brownley and Kimmich xi). Women’s autobiographies have been “excluded from the tradition of autobiography because women’s writing tends not to have the same form as men’s” and because “women’s subordinate social status” was deemed inadequate for “the exercise of authority as writer” (Babbitt 215). So, once again, as with women’s fictional writings, the patriarchal society has rendered these writings invisible because it does not value them (Lane xi).

Indeed, it has been the expected form of a story, not always compelling, about male personal growth in the public sphere that has in recent decades come to be questioned. Many critics now reject the word “story” and all the expectations that go along with what that concept implies. As Babbitt points out, writers in the Brownley and Kimmich collection, depart from the former idea that women’s autobiographies need to be “stories” that “move linearly from youth to old age” (215). According to Caroline Breashers, autobiography is more than a ‘story” of personal growth; she urges us to “recuperate” (a term she borrows from Bonnie Kime Scott) life writings and restore them to “a historical, creative, discursive and economic context” (202). Johnnie M. Stover, too, rejects the term “story” choosing “narrative” instead because autobiography is more than about personal growth—it is “life experiences within a historical context” (135). Likewise, Assiba d’Almeida, in writing about the autobiography of Kresso Barry, points out that Barry does not consider her life a story or even a “tale” but rather a “struggle [. . .] of a woman’s life located in history [. . .]” (69). Likewise, Albert Stone tells us that autobiography is not “simply a story” but writing that has “a complex nature and varied social uses: it is simultaneously historical record and literary artifact, psychological case history and spiritual confession, didactic essay and ideological testament” (2). Rather than “story,” Stone prefers the term “narrative” (3) and contends that “as literature [i.e, story] autobiography is indeed a problematic mode of discourse” (6); he sees autobiography as “the history-making act” representing the “highest and most instructive form in which the understanding of life confronts us” (3). Because each autobiography is a “cultural artifact celebrating individual consciousness, style, and experience,” says Stone, “its readers must learn to adjust critical focus from individual text to social context” (8). This is a very important concept because until this happened, as Brownley and Kimmich point out (xi); works by women just were not to be considered as “real autobiographies” (xii).

Once scholars moved beyond seeing autobiography as a story, its value as historical, cultural, political, and economical record placed it in a more prominent place in the academy and made it even more important to discover autobiographical writings from women of an earlier time and to bring them to the forefront for the sake of our students and women at large. It is absolutely imperative that we have a sense of the American female experience. William Dean Howells was one of the first to recognize the importance of autobiography—again, not because of its compelling story—but because it “indeed mirrors and creates the social, historical, and aesthetic varieties of our national experience” (qtd. in Stone 2). Later, Stone would come to share that opinion:

At any moment, autobiography may be viewed as a collection of such acts of self-performance unified by shared cultural values and fashionable metaphors of self. Women’s perceptions of these crucial stages will differ from men’s, however, just as period, class, economic, and racial factors influence one’s choice of childhood, youth, or maturity as the vital center of a narrative. (3)

Stone, here, captures the essence of what feminists have long contended—that women’s autobiography is more than a “story” that is developed chronologically or in the traditional literary format; it is an essential lesson in the history of women and an important tool for helping women gain equal rights because “a historical consciousness speaks out of singular experience, for some particular social group, to a wiser audience” (Stone 3). Likewise, Robert F. Sayre says, “Autobiographies [. . .] offer the student in American Studies a broader and more direct contact with American experience than any other kind of writing” (11). Those of us from the liberal arts tradition view autobiography as essential to our studies because these narratives are “naturally interdisciplinary” (2). Like d’Almeida, we believe “[t]he object of autobiography is to not only entertain but also to instruct [. . .] since the tale has value only as far as it reveals something of the society to the society” (69) because “memory is linked with history and here autobiography functions as history—even though selective-belonging is not only to an individual but to a people” (67). Elia Peattie, like Irene Assiba d’Almeida’s Barry, reveals “not only an individual life, but also cultural, social, political, and historical elements of life, [. . .]” (67) and while Barry’s revelations are about life in Guinea, the same concepts can be extended to Peattie in Chicago. As with Barry, Peattie, too, has “many facets of the self [that] contradict each other” (67). Stover, who discusses the importance of nineteenth-century black women’s autobiography says that it is “much more than a personal narrative [stress on narrative is mine] that merely remarks on [. . .] personal growth; it is a social discourse” that records “life experiences within an historical context” (135).

Jane Tompkins agrees that earlier works must be studied because “they offer powerful examples of the way a culture thinks about itself” (xi). Further, she says, we need to consider these works “in relation to the beliefs, social practices, and economic and political circumstances that produced them” (xiii). While Tompkins is discussing fictional writings, many feminists would apply it to women’s autobiographical writings as well. Specifically, I would like to extend it to Chicago’s turn-of-the-twentieth-century women autobiographers. It is crucial to scholars and other interested people who want to see a clear, more comprehensive view of the city at that time, for as Tompkins says, herein lies the discovery of “the problem or set of problems specific to [that time and culture] (38), and of the “social reality which the authors and their readers shared” (200).

Clearly, the modern women’s movement is interested in social history and recognizes that social reality was quite different for women and men. As the social reality was different in the fictional writing of Chicago males and females, the social reality reflected in autobiographical writings of men and women is different. As Brownley and Kimmich point out, autobiographical writings by women were unacceptable to the male patriarchy, especially if they wrote “life stories that diverged from the textbook models” (xii). The textbook model has typically been the male reaching self-fulfillment, all on his own, in the public arena.

Women present different models and ground their autobiographies in their personal lives with a private view. Brownley and Kimmich state:

[W]omen imagine new ways to write autobiographies that reflect their experiences. For example, women write autobiographies that emphasize relationships because they are accustomed to thinking of themselves in relation to others as somebody’s daughter, wife, or mother. The focus on relationships also means that women’s life writings typically concentrates on private, or home life in contrast with men’s texts, which often foreground the authors’ activities in the public sphere.(1)

Unlike her male counterpart, Brownley and Kimmich say, “the typical woman writer acknowledges that her life is a part of a larger social fabric [. . .] and may refuse to take credit for her successes by bowing to the social norms that link femininity to self-effacement [. . .]” (1). Those same social norms affected ways in which nineteenth century women confronted and wrote about problems that they faced—some of which were not discussed publicly even under the guise of fictional characters; problems which challenged the patriarchal views of women and their place in society or those vaguely defined as “female troubles” are often found only in personal letters or autobiographies. The critic, Sidonie Smith, reminds us to:

remember that there is no monolithic autobiographical discourse, no one totalized set of policing actions, no one regime of truth operative at particular historical moments, no one location for a reproductive or contestatory practice. There are multiple technologies of autobiographical writings [. . .] self-writing practices are intermingled with other writing practices, and are brought to bear on myriad personal, social, political, economic, physical contests. (45)

For Smith, and many of us, female exclusion, of both fictional and autobiographical works, reveals significant differences according to cultural and historical context (45).

What we generally accept as the first generation of autobiographers was born in the 1860s and ‘70s and had careers between 1895 and 1920 (Sayre 25). Their works reflect the industrial civilization of which they were a part. Their works were usually titled The Autobiography of . . . , and, for these writers, there was frequently a yearning for childhood when they were innocent and free of responsibility. This seems especially true of women who, raised in the “cult of true womanhood,” [1] suffered a loss of Self upon marriage and took upon themselves the rearing of children who would perpetuate the ideals of America.

There are many similar characters among this group of autobiographers, and while Elia Wilkinson Peattie shares some of these general characteristics, she is in many ways very different from other first-generation autobiographers. Peattie titled her memoirs The Star Wagon and wrote solely for her children. She felt that the title “memoir” was “too impressive” for her life, which she felt was only “noteworthy” to her children (1). Because Peattie's austere childhood was stifling, there is no emotional looking back. The things that Elia valued most, books and music, were considered unaffordable or unimportant by her father (Frederick Wilkinson) who viewed them in the same light as he viewed “hired help” for his over-burdened wife. Taken from school in the seventh grade, Elia became the unpaid “hired help” in a world without books or music and assessed life as a “dull business” (40). Unlike many of her female counterparts, Peattie was able to discover her Self through a career and a marriage of equality where she shared the roles of responsibility and leadership with her husband Robert—who was not “prejudice against the work of women” (304). Albeit, throughout the manuscript, she struggles with feelings of guilt and inadequacy as a mother because she sacrificed domestic cares for a professional career that often took her away from home and family for days, weeks, even months at a time. It was not her family, but her writing, that Peattie identifies as “the thing that seemed to justify life” (102).

While Thomas P. Doherty contends that autobiographies are “oddly silent about the political and economic structures” (96), Peattie's memoirs and other writings demonstrate that she was not afraid to challenge male authority: she supported radical suffragists, railed at the tribulations of dealing with male jealousy and sexism in the work place, condemned overbearing men and male politicians who cut important social causes, usually started by women but taken over by men, from their budgets. Peattie, herself, once refused an invitation to be presented to the Pope because she “had no respect for his assumptions of authority” (237) and cautioned a female acquaintance against relinquishing her “intellectual liberty” to the Catholic Church (373). She criticizes the double standards for females and males and calls a small-town woman socially ousted by her community, for what it perceived to be the sexual impropriety of a female (but not an impropriety for her male counterpart!), “a plain fool, a pious, filial fool” because she “stayed with her slayers who slew her daily” (121). Unlike male autobiographers, Peattie clearly was not silent about the institutions or customs that render women invisible.

And, so, it is important to study both women's fictional works and their autobiographical writings as well. While moments of critical importance may not be covered in one area, they may be covered in another, and thus the full picture of these early women can be gleaned only by looking at the entire body of writing. This is especially true for the nineteenth-century woman whom the ideology of gender inevitably silenced in the “cult of true womanhood.” Many were hesitant to discuss issues of great importance, like child bearing or friendships with other women. Even Peattie, who confronted authority and the patriarchal institutions and customs that rendered women invisible, found it difficult, or perhaps inappropriate, to write about “female troubles” and close female friendships in fiction. She was somewhat more open in her memoirs, recalling, or perhaps justifying, that the reason for a wet nurse was because she could not breast feed her child; yet, in her memoirs, she does not write about the loneliness she felt when separated overlong from her dearest friend and fellow author, Kate Cleary. However, in Elia’s personal letters to Kate, the longing is quite clear: “Sunday night and dull as a Henry James novel...If only you were here to chat ... I have ached for you” (June 7, 1891). Later that same year, following the birth of Elia’s third child, she wrote: “The only complication during my illness came from an old trouble with my breast and resolved into drying up of my milk...” (August 21, 1891). Thus, we can only learn about these intimate issues from careful study of various types of autobiographical writings.

While many of these self-effacing women found it difficult to write about subjects like confusion, ambivalence, and gender differences, Peattie did not. However, while her fiction is straight forward and concise, her memoirs and personal letters are not. Kate Barrington, in Peattie’s suffrage novel, The Precipice, meets ambition head on and does not struggle with confusion and ambivalence, nor justify her choice to have a career outside the home. Moreover, she negotiates a marriage that is an equal partnership with a commuter marriage. Conversely, when Peattie writes her autobiography, she relies on the star wagon metaphor to talk about her personal ambition (this issue will be explored in greater length a bit later) and reminds her children repeatedly that it was for them she had worked.

Like other female autobiographers, Peattie has no “obsession with Self” which Mary Mason contends is not a central theme in women's autobiography, as it is in male autobiographies (44). Like other women autobiographers, Peattie does not write a “story” about her personal growth as a writer nor her personal involvement with important people; she does not move “linearly from youth to old age” (d’Almeida 67). She does not exclusively organize her autobiography around the chronology of her own life; rather, as Stone tells us is often the case with women autobiographers she chooses something else “as the vital center of [her] narrative” (3). It is loosely coupled around her children, and she often drops important discussions of her own life to talk about her children. This pattern of loosely coupling her life chronology with vignettes about her children is demonstrated throughout her memoir. A specific example of loose coupling occurs when she digresses from her first meeting with Willa Cather, then a graduate student at the University of Nebraska, to tell a story about her son. While Peattie, on one hand, felt ambiguous about family life and warns about too much sentimentality, her children were her center; her goal in life was to raise them out of poverty. The chapters dealing with her children are titled and placed in the center of the manuscript, but she apparently felt it was not important to title those dealing with her own life.

Thus, in an overall comparison of male and female autobiographies, The Star Wagon is complex, like Peattie herself. At times she writes like a man, at times like a woman; at times she is a product of her culture, at other times she is a leader. She is a conservative and, yet, a liberal; she is acquiescent and defiant; she is a progressive, she is not. Elia recognized these complexities and struggled with them. They often created problems for her, and she struggled with guilt for most of her life. These complexities are an inherent part of her. Susan Babbitt, in reviewing Shari Benstock’s work, finds that these complexities, as I have found in Peattie (and, Peattie found in herself) are understandable; she says: emerging from “the consideration of women’s autobiography is the contradictoriness, or at least the complexity, of self-understanding—in particular, the recognition that self-awareness is not the direct result of one’s perceptions of oneself” (216). Likewise, d’Almeida says of Barry, “many facets of the self contradict each other” (67).

Peattie, like other female autobiographers, linked her female identity, in particular her ambition, to some “other” and it is this “other” that allowed Peattie, as well as others, to write about themselves—what Stone calls “acts of self-performance unified by shared cultural values and fashionable metaphors of self” (3). For Peattie this “other” is the image “star wagon” which serves as a self-assessed metaphor for her aspirations; as her aspirations change, so does the wagon's cargo. She says that long before she had read Emerson, she hitched her wagon to a star (17). Peattie says that her first memory is of a tiny red wagon which she was “drawing” and feeling as if she were “floating” (7). A gifted reader in grammar school, Elia gained self-confidence and began to question the theories of both her books and teachers. “Always within me,” she says, “was the idea that I could do something splendid. [. . .] My little red wagon had become myself” (17). With her newly acquired confidence, the young Elia set forth “bound upon some glorious journey” with an “extraordinary faith” in the wagon's “destiny” (18).

In the austerity of her early years, however, Elia's “floating moments” (7) were few. Her patriarchal father was anxious, irritable, argumentative, excessively pious and felt books and magazines were unaffordable (2, 9, 10); although he, himself, was college educated. He was too often gone from home, “ostensibly to work” (18), leaving Elia's nervous, overworked mother (Amanda Cahill Wilkinson) to run the domestic sphere and care for their six daughters (two sons died in infancy). As the eldest, Elia was taken from school in the seventh grade to help with family responsibilities. Studying her father's old college books and the dictionary, Elia kept “hoping for something glorious to do but couldn't seem to find it” (21); “I could not decide on the star; or no star would hold still long enough for me to hitch to it,” she says (21).

For all of her life, Peattie would value education and, consequently, resent being taken from school, where she claimed that with a little coaching, she would have done very well—her grandmother was a friend of Lucy Stone, one of the first women educators, and her father was a graduate of the Kalamazoo Law School. Interestingly, though, Elia took her own daughter, Barbara, out of school at an early age so that Barbara could serve in the domestic sphere. While Peattie laments that she had placed too many burdens on Barbara when she was too young to bear them, she seems completely unaware of the replication, another of the many inconsistencies in Peattie’s life—an example of d’Almeida’s “many facets of the self contradict[ing] each other” (67).

In those austere early years there was little to enhance the quality of life because Fred Wilkinson saw no use for such things; yet, the artistic side of young Elia was lying just beneath the surface. She relies on the wagon metaphor to describe her awakening to the arts; an awakening, described in rather orgasmic terms, caused by the first violin that she heard: “I was lifted up, near to tears, near to crying out to the player to stop, that I could stand no more. He went on and on. I trembled all over” (7). It was one of those “marvelous floating moments,” she says, “like the one when I had drawn the little red wagon” (7). Another awakening to the arts came when Frederick Wilkinson bought a piano “on time.” Elia “fell upon it with a passion” and it became a “refuge [. . .] a door of escape from monotony [. . .] and ugliness” (36) until Wilkinson failed to keep up the payments and the piano was repossessed. Elia fell in love with Shakespeare, whose works she discovered in her uncle's home, and took elocution lessons—until those payments, too, stopped. Under such stifling conditions, the young Elia experimented with writing and at age eighteen modestly composed “Noontide @ Midnight” an unpublished poem (Attached as Exhibit I). However, under such bleak and stifling conditions, inspiration was difficult, and, despite having the “most extraordinary faith” in the little wagon's “destiny” (18), Elia found life to be “rather a dull business” (35). Life was so dull, in fact, that Elia, like many ambitious women of the era, suffered a breakdown from nervous prostration (57). Painfully relived in her memoirs, Peattie's breakdown closely resembles that of Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

Nevertheless, “the destiny” of the star wagon changed when Elia began attending Sunday school parties at the local Baptist church—an act of direct disobedience against her father who objected because the children wore masks. While Wilkinson forbad prayers and spewed forth pious venom about Elia dooming the family to hell, she danced away the night with Robert Burns Peattie, whom she would later marry. Robert was already earning his reputation as a journalist working for the Western News Company. Fred was not impressed, but Elia was—Robert whistled light operas; his first gifts to her were books, followed by flowers (42-44). Immediately the star wagon became “heaped and running over” with a “shining, iridescent cargo” that “trailed its splendors on the ground” and “flung them to the winds” (44). A tell-tale sign of their relationship, and of Elia's strong personality, is in her recollection of their courting days when “[h]e'd sit on the back seat of the surrey, I on the front seat, driving [. . .]” (52). This event would foreshadow a marriage of equal partnership and shared leadership. Robert was exactly the opposite of her chauvinistic father and grandfather whose absolute authoritarian rule she despised—and condemned at a very young age. Her courtship with Robert brought “much cargo” to the star wagon, and although it was “a commodity without a name” she recognized the “vague stirrings of power” (53).

For a short portion of her life, Elia makes no reference to the star wagon; these are the early years when she and Robert lived in Chicago and for the eight-year period when they lived and worked in Omaha, Nebraska. However, after dealing with jealous, disgruntled males in Omaha's journalistic field, she welcomed a move back to Chicago and again returns to the metaphor: “The star wagon was carrying appropriate freight again, and dumping many miserable things” (142).

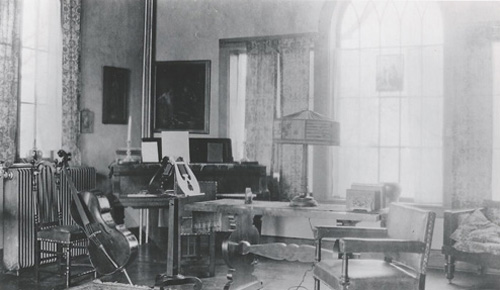

The middle years of life for Elia and Robert (1896-1917) were spent in Chicago, many of them in Elia’s childhood home—a house they bought from the Wilkinsons and remodeled with money Elia earned from writing 100 short stories in 100 days for the Chicago Tribune. Elia refers to this time as the “busy years at the House-home” when the star wagon had carried much cargo—“a store of hidden thoughts, of aspirations” (418).

Toward the end of the manuscript, Peattie relies on the metaphor to access her life's accomplishments. She deplores having put “so poor a cargo in the Star Wagon” (363) but later contradicts this assessment as she answers the self-imposed question: “Did I [. . .] have much conscious inner life? Did I put much cargo in the Star Wagon? Secretly yes” she says, adding: “aspirations I would not have named, nor dare I name them now, so pitiably short of them have I fallen” (418). Later, she describes those unattained aspirations in the star wagon's cargo as “only the grasses of a past summer and leaves crisped and shrunken that would not again rustle in the wind” (464). The “poor little Star Wagon” carries “no splendors [. . .] ambition now is for our children” (480), says Peattie.

Yet, if one word can be the key to understanding or categorizing a life, the word “ambition” is most applicable for Peattie. Her son, Donald Culross Peattie, in his autobiography, Road of a Naturalist, acknowledges that his mother “began to be professional in a day and a family [Wilkinson] where talent was acceptable in a woman only as a pretty accomplishment” (53); he recalls being lulled to sleep at night by “the peck of my mother's typewriter [which] sounded from [. . .] early until late” because in his home “publication was [and still is] a merit of character” (116). Clearly, Peattie's ambition was to write; specifically, she wanted to write fiction.

While most students and scholars today have come to know Peattie from her fictional writing (The Precipice was republished in 1989), she began her career in journalism—a job that in 1890 was finally deemed “suitable” for women (Weiner 29). It is difficult to determine exactly when Peattie first began writing for the Chicago Tribune, but she writes of her job as the “first girl reporter” for the Tribune, acknowledging that it made her the “second girl reporter” in the City (66). She first discusses writing short stories for the newspaper after the birth of her daughter, Barbara, in 1885; however, other writers, for example Philip Kinsley and Charles Collins, state that she came in 1884 and that she was the Tribune’s first “girl reporter” and the second “girl reporter” in the city’s newspaper history (82, 17). Her first experience at the Tribune was rewarding: “I proceeded to fill my lungs with life” she says (66).

When the Herald in Omaha, Nebraska offered Robert a position that included a job for Elia, the Peatties moved. In Omaha, Peattie quickly established herself as a writer making life-long friendships with the likes of Willa Cather, Henry Blake Fuller, Hamlin Garland, and William Jennings Bryan. Peattie wrote the first western review of Bryan—whom she considered to be “handsome and good looking” and became involved with the Progressive movement, co-authoring the Populist propaganda tract, The American Peasant. She published “Jim Lancy's Waterloo” in Cosmopolitan and, later in book form where over one million copies were printed and distributed as propaganda for the Populist Party. Donald Culross Peattie recalls how she took on the railroads for exploiting the West and wrote so many letters that the railroads threatened to sue, until, finally the railroads and banks squeezed the newspapers (130). For her hard work and favorable reviews, Bryan dubbed her, “The first Bryan man” (128). Revealing another complexity, Peattie’s progressive agenda waned despite her involvement with various organizations such as education and women’s clubs.

Like many ambitious women, then and now, Peattie was torn between ambition and domestic duties, her greatest and most intriguing complexity. As she enjoyed a marriage that was an equal partnership, traveled, and worked outside the home, her early works advocated the domestic sphere and traditional acquiescence for women, especially the whimsical 100 short stories that she wrote in 100 days for the Chicago Tribune. Her work and work-related travels required that she leave her children in the care of nurses, maids, or family members. Moreover, it was her ambition-driven professional work that gave her life meaning; it gave her, she said, “a sense of eating life and no matter how much I had, I was still unsatisfied” (102).

As indicated earlier, while Peattie must rely on a metaphor to discuss her own personal ambition, she allows her outrageous protagonist, Kate Barrington, a suffragist, in The Precipice (written after Peattie shifted to a more liberal ideology) to speak boldly: “[Ambition] ought to be a credit to me! It's ridiculous using the word 'ambitious' as a credit to a man, and making it seem like a shame to a woman” (137). Meanwhile, Peattie spends a good deal of time in The Star Wagon justifying her own ambition and career. While her memoirs reveal much guilt, especially concerning the domestic duties which she heaped upon her daughter Barbara, Peattie's goal, strongly influenced by her own early life of austerity, was to raise herself and her family out of “poverty and inconspicuousness” (200)—a justification that she repeats many times. While she felt that her first job as society reporter for the Tribune was a “mitigation” (64) because she was “snubbed” (63) in the fashionable houses, and though she “loathed” (63) the injustices, she says, “we had to have more money in the little house and I was getting it” (64). Elia's “juggling act” between the professional and domestic spheres (Falcone 38) began early and is especially evident in the method the Peatties adopted for writing fiction in the evenings: Elia would sew and dictate to Robert while “stirring the cradle” with her foot (63). Her second income added much needed money to the house and growing family. When the Northwestern Railroad Company commissioned her to write a travel guide, she placed her children in the care of family and left for an extended trip to Alaska. She relished the adventures that for the first time made her “free of house-keeping trammels” (73). While Elia might have concentrated on her fiction, she accepted a position as literary critic for the Chicago Tribune—a position that left little time for creative writing. It was this job and the endless reviewing of books, she later claimed, that destroyed her creativity: “My talents were slain, but the bills were paid, the children educated. [. . .] It was for them, after all, that I had worked” (464). And she acknowledges: “I did no end of stupid things to my children. [. . .] They have much to forgive me for” (167). Other parts of the manuscript contradict her contentions here and reveal that it was her ambition, her professional work, not her family, which was “the thing that seemed to justify life” (102).

Peattie's early ambitions, nurtured in Omaha, seemingly were absorbed by osmosis from the city of Chicago, which became one of the most ambitious cities in the world. Turn-of-the-Century Chicago was the epitome of Thorstein Veblen's “conspicuous consumption;” it was for Carl Sandburg and many others, the “City of Big Shoulders,” “wicked”, “crooked,” and “brutal” yet “the heart of the people” “laughing” and “proud” (“Chicago”). Sandburg's description, like Sherwood Anderson's, “the city [. . .] like your own soul,” (395) aptly encompasses Peattie’s “insider”view of Chicago as articulated in her review of Norris’ book. It was the center of literature and architecture, and, in 1893, Chicago displayed all of its accomplishments in the Columbian Exposition. Here, in Chicago's heyday, Elia Peattie spent her prime years, 38 of them, actively engaged in journalism, literature, drama, the woman's club, the suffrage movement, the settlement house movement, and the University of Chicago, which was just opening its doors to women. Well aware of her opportunities, Peattie declares, “A city is a great home” (106 The Precipice). Chicago was, indeed, an exciting place for an ambitious, middle-class woman.

Middle-class women by the 1890s were finding their way into jobs that were both respectable and allowed them to earn a decent living. Lynn Y. Weiner lists those jobs deemed “suitable” for women as: telegraphy clerical, sales, decorating, journalism, and telegraph work (29); yet, she points out that “fewer than one in ten married women worked for wages” (83) with less than 2 percent of them employed in occupations that could be defined as white-collar work (87). According to Mrs. M. L. Rayne, free lance writers were typically paid $1.50 - $2.00 per column—if the woman could give “a quick and comprehensive digest of the news—a tender and pathetic sketch in which are all the elements of a first-class drama [. . .] and a style that will compare with Ruskin (36). Those who were bolder, like Mrs. Fitzgerald, of the Chicago Inter-Ocean, could earn more money. She took the position of “night reporter, and would go into the office at midnight with police news. No one molested her, and she retained her position until something more desirable offered itself. The salary for such work averages about $10 a week” (45). Rayne noted also that Harper’s Bazaar [. . .] is always desirous of receiving good short stories [. . .] and pays from fifteen to twenty dollars for them [. . .] (45). By 1885 Peattie was adding “a hundred a month to our income” (55) and, by the 1890s, her lectures earned “anywhere from $16.00 to $100.00" (117).

It was a unique situation for middle-class couples, like Robert and Elia, to work. Weiner points out that there was an “inverse correlation between family income and the employment of wives” with married women working only when their husbands earned low wages (84); “a minority of wives worked not because of absolute economic need but because of relative economic need—the desire to better the standard of living for their families” (86). It was for this “relative economic need” that Elia worked, and in their professions, as in everything else, Robert and Elia shared an equal partnership and worked together to facilitate each other’s careers. Fanny Butcher, who became a personal friend of the Peatties, acknowledges that the “book columns of the Chicago Tribune really were a husband and wife production” (K16). Robert valued Elia’s career as equally important as his own; he supported her in her many travels which took her to far away places for extended periods of time. Couples with this type of marital partnership were rare, as Barbara Mayer Wertheimer points out in her discussion of Mary Kenney O’Sullivan and her labor-editor husband, Jack O’Sullivan. Jack insisted that his wife keep on working after their marriage, even after the children came, “but he helped her with the work at home to make it possible for her to do so.” (267). Those couples who managed to rise above the proscribed customs of the day to earn two salaries found themselves, as did the Peatties, advancing financially at a rate previously unimagined.

Much of the time, Robert was also earning a tidy sum. At the time of their marriage, when “a regular job was $10.00 a week in a bank or book store,” he says, “I was drawing $25.00 a week as a reporter.” It was this impressive salary that earned him the respect of Fred Wilkinson (20). Even with two salaries, though, the Peatties, often struggled. Robert’s health was precarious, and he was not always able to work. Sometimes, probably due to lack of regulations, people took advantage of them. Once, while he was working in Denver to regain his health, he says his “small salary was not always forthcoming;” meanwhile, back in Omaha, at the World Herald, Elia “was forced to accept, in place of money, orders on advertisers for things [they] didn’t want,” which caused them “to lose a good deal of money” on the house they had purchased (25). But, like Elia, Robert, too, was always looking for ways to add additional money to the family budget; he said that he sometimes earned “bonuses for making improvements on the writing” in the newspaper office and made an “additional $5.00 here or $15.00 there” (68). Robert, who always encouraged Elia to write, to work, to be creative, grew to depend upon her second salary and noted, “For years a pretty certain source of income was Youth’s Companion” [. . .] Elia’s juvenile stories were still bringing in a “small sale many years later” (26). He once went to New York, where for two months he made no effort to look for work, leaving Elia “busy on the World Herald and doing magazine stories to keep the pot boiling” (67).

So, Chicago afforded many opportunities to the hard-working, middle-class woman who could write. In her 1893 book, What Can a Woman Do? Rayne cautions, yet challenges, young women to write: “I urge women to be sure of their ability before they enter the flinty paths of journalism, where it is a sin to be ignorant, and where you are expected to be wise, witty, sensible, poetical, and versatile for very moderate pay [. . .] be versatile enough to write grave to-day and gay to-morrow” (44). “If a woman is born with a talent to write,” says Rayne, “she will write—there is no possible doubt about that” (47). Rayne thought that her modern woman had come a long way from the 1840s (although it seems that “Mrs. M. L. Rayne” could not write without identifying herself under the designated title for married women) when, she reminded her readers, there were only a few industries that were open to them—keeping boarders, setting type, teaching needlework, tending looms, and folding and stitching in book binderies (3). For middle-class women, like Elia, it was time to move beyond domesticity.

Out of this creative, intellectual milieu in Chicago there arose two polar types of literary institutions, the studio and the newspaper. Interestingly, Peattie was generally well respected in both camps. She was one of the early founders of the elite Little Room, where Chicago's literati met. When Hamlin Garland and others formed the all-male Cliff Dwellers Club, Peattie, Clara Laughlin, and Louise Hackney founded the Cordon Club for professional women. Peattie was one of the most celebrated literary critics in the City; Butcher notes that to be invited to the Peattie home for Sunday brunch was the “final literary accolade,” and recalls her own “initiation into that sacrosanct atmosphere” where the literati gathered (K16). Likewise, Kinsley points out that the Tribune ranked its first “girl” reporter with the best authors of the day (82). Peattie's ambition produced astonishing results in both camps. Robert, who included an extensive, though incomplete, bibliography of his wife’s works in his autobiography, points out that she read some 10 books a week with her reviews totaling 5,000 columns; she wrote essays, lectures, poetry, plays, and operas. She published several hundred short stories for newspapers such as, Boston Transcript, New York Evening Post, and Chicago Tribune, as well as in prominent magazines, Cosmopolitan, Collier’s, Harper’s Bazaar, Harper’s Weekly, Lippincott’s, and Youth’s Companion; for a time she ran a department in the Designer and another in the Reader; she published thirty-two books (Unedited 454), and there were a number of unpublished manuscripts.

However, there came a time when Peattie's work floundered, as she was well aware when six manuscripts were returned “like hungry cats” (322), and while there may be several reasons for her inability to meet the public’s expectations, it appears that the primary reason is that she could not adjust her conservative/genteel ideologies to accommodate the new morals of the changing times. When the second wave of the Chicago Renaissance replaced the “genteel tradition,” the populace lost interest in her writings. While early in her career her works had been “too radical” they were now considered “nauseatingly virtuous” (322) in comparison to Theodore Dreiser and others. Not only did Peattie’s writings not reflect the new sexual mores, Peattie took a solid stand against sex in literature in her Tribune book reviews. She held Dreiser’s Sister Carrie in the utmost disdain calling his work “the epic of a human Tomcat [. . .] [a] back fence narrative” (“Gossip” 12). This “vituperative” attack on Dreiser caused her to lose favor with male critics, like Burton Rascoe, who referred to her as a “formidable bluestocking” who “rather ran the literary roost in Chicago” (324). Her strong stand against sex in literature seems to have been viewed as too Puritanical. Interestingly, she protests that Garland had “compromised with the juvenile taste of America,” and, in order to sell his works, had abandoned the “austere and tragic qualities of 'Main Traveled Roads' producing an “innocuous sort of material” that had wasted his “vigorous and heroic talent” (131).

It is evident that Peattie’s professional reputation was floundering. Robert’s memoir offers some insight into the shift of interest in Elia and her writing. He says that she became “hated by the people of the Little Review who were rebelling against the literary bourgeoisies. Elia put a hoax on them to show the crowd that their attitude could be assumed at will by anyone” (26). Elia adopted the pseudonym, Sade Iverson, a young, homeless girl and played on the liberal ideals of the younger group of writers. It appears then that change in the political climate likely caused the lack of interest in her works and their traditional themes. The older, more genteel, women of the era emphasized community and social responsibility; as evidenced in the women’s clubs and Hull House, they were committed to a life with purpose and meaning. The young women of the next generation emphasized the individual.

Perhaps another reason her work floundered was that she lost her zeal to write. Peattie, herself, analyzed the problem: “the eternal reading and reviewing of books for twenty years [had] destroyed my originality and [. . .] vitality” (464). Her work was also affected by the untimely death of her daughter, Barbara, who died at the age of 30 leaving behind unfinished poems and three little boys for her husband and family members to care for. Peattie says that with Barbara's death in 1915 she could no longer give her characters life (252).

In 1917 Robert accepted a position with the New York Tribune, and the Peatties relocated, but never adjusted, to New York. Elia explains that New York with its “days of aching anxiety” and “anguish” was “no substitute for a real home” and hence “could not, in the nature of things, compare in happiness with the life at the House-home in Chicago” (465). Although her professional life had ended, she was made a member of the National Poetry Society, the City Club, and the National Arts; yet, she was as “lonely as a cloud in these places” with “no initiative” and heavy heart (486). While many of the Chicago journalists and literati—the Tafts, Rascoes, Dawsons, Fields, Cather, et al—lived nearby or visited, they seem to have become a rag-tag lot who had lost mates or sons in the war, and Elia laments that while they “had home-like times together” they were “all homesick for the homes that were no more” (469). “In New York there are no neighbors” (471).

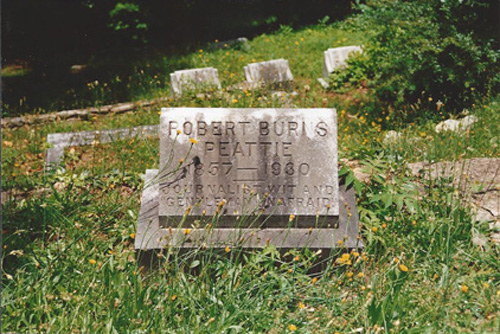

Consequently, after only three years in New York, Robert retired, bringing to an end his 40-year journalism career. He had begun as a young man with the Western News Company in Chicago; he would eventually work for the Chicago Times, Daily News, Omaha Herald, World Herald, Denver Sun, Nonpareil, and the New York World, but more than 20 years were spent with the Chicago Tribune—either as a member of the editorial staff or as their New York correspondent, which is where he was working at the time of his retirement in 1920. His pseudonym, as disclosed in “The Story of Robert Burns Peattie,” was Herbert Claxton (75). He was known to be the witty intellectual who was always a perfect gentleman.

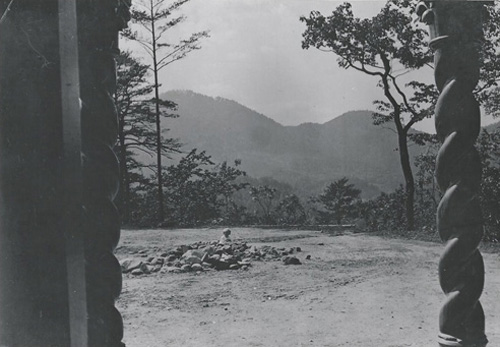

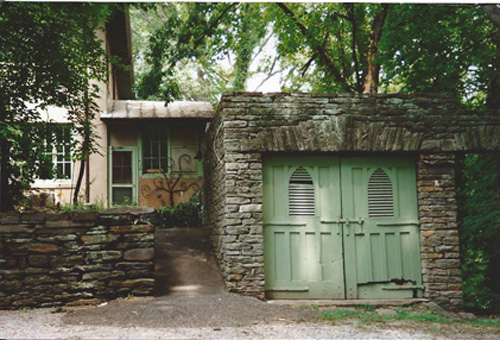

The Peatties decided to retire in Tryon, North Carolina where they had visited many times, and where Barbara Peattie Erskine's “Villa Barbara” still stands today. “The beauty of Tryon was like a welcome home” says Elia; again, she notes that she was “free from all domestic care” and returned to her writing—poems, plays, and lectures (472). Peattie became active in the Lanier Library where she had first lectured in 1901 (Falcone “Elia Wilkinson Peattie” 15); the Lanier now served as an outlet for her writings. She helped to form the Drama Fortnightly, a play reading society at the Lanier Library which eventually emerged as the Tryon Little Theater; both institutions remain active today. She wrote plays and the Tryon School Song; she was active in women's activities, but says, “ambition now is for our children” (418). In the earlier years there was “too much stress for philosophy,” and “aspirations [. . . were] as flowers at which one snatches by the wayside, running on some swift and imperative errand” (418).

Peattie, like her Chicago sisters, was committed to a life of purpose and productivity. She valued "intellectual development, independence, and work. Likewise, she both promoted women's comradeship with men (especially when wartime patriotism weighed heavily) and criticized romantic feminine self-sacrifice” (Bremer & Falcone 6). When, in middle age, Peattie turned toward a more liberal ideology, she advocated these values for all women, as evidenced in her memoirs and The Precipice which advocates many different roles for women and urges readers to appreciate ambition in women as we do in men. Thus, the star wagon is an appropriate metaphor for the memoir of this Chicago woman, who, like the other lost sisters of Willa Cather, worked for “justice, love, freedom, knowledge, utility” (Emerson, Society & Solitude).

Works Cited

Aaron, Daniel. Introduction. The Memoirs of an American Citizen. By Robert Herrick. Cambridge: Belknap P of Harvard UP, 1963. vii-xxx.

d’Almeida, Irene Assiba. “Kesso Barry’s Kesso, or Autobiography as a Subverted Tale,” Research in African Literatures 28.2 (1997): 66-82.

Babbitt, Susan. “Women and Autobiography,” Hypatia 18.2 (2003): 215-18.

Breashers, Caroline. “Scandalous Categories: Classifying the Memoirs of Unconventional Women,” Philological Quarterly 82.2 (2003): 187-212.

Bremer, Sidney H. Introduction. The Precipice. By Elia W. Peattie. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1989. ix-xxvi.

———. “Willa Cather's Lost Chicago Sisters.” Women Writers and the City: Essay in Feminist Literary Criticism. Ed. Susan Merrill Squier. Knoxville: U of Tennessee P, 1984. 210-29.

Bremer, Sidney H. and Joan Stevenson Falcone. “Elia Wilkinson Peattie.” Women Building Chicago 1770-1990: A Biographical Dictionary. Eds. Rima Lunin Schultz and Adele Hast. 2001: Indiana UP.

Brownley, Martine Watson and Allison B. Kimmich. “Introduction.” Women and Autobiography. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources. 1991. xi-xiv.

———. “Women’s Lifewriting and the (Male) Autobiographical Tradition.” Women and Autobiography. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources. 1991. 1.

Butcher, Fanny. Chicago Tribune. 15 Mar. 1964. K16.

Doherty, Thomas P. “American Autobiography and Ideology.” The American Autobiography. Ed Albert E. Stone. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1981.

Duncan, Hugh. The Rise of Chicago as Literary Center 1885-1920. Totowa, NJ: Bedminster P., 1964.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Society and Solitude.” 1899.

Falcone, Joan Stevenson. “The Bonds of Sisterhood in Chicago Women Writers: The Voice of Elia Wilkinson Peattie.” Diss. Illinois State U, 1992.

———. “Elia Wilkinson Peattie and the Lanier Connection.” Address. Lanier Library Association Annual Meeting. Tryon, NC, 14 April 1996.

Kinsley, Philip. The Chicago Tribune: Volume III 1890-1900 Its First Hundred Years. New York: A. A. Knopf, 1943.

Lane, Ann J. Introduction. The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. By Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1935. xi-xxiv.

Mason, Mary. “The Other Voice: Autobiographies of Women.” Life/Lines: Theorizing Women's Autobiography. Ed Bella Brodzki and Celeste Schenck. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1988. (19-44).

Peattie, Donald Culross. The Road of a Naturalist. Boston: Houghton, 1941.

Peattie, Elia Wilkinson. “Elia W. Peattie on ‘The Pit’ and a Book of Essays." Chicago Daily Tribune 24 Jan. 1903. 13.

———. “Gossip of Books of the Day.” Chicago Daily Tribune 14 Feb. 1915. 12.

———. Letters to Kate Cleary. Little Room Papers. Newberry Library, Chicago.

———. The Precipice. 1914. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1989.

———. “The Star Wagon.” Unpublished memoir, 1929. Lent by Mark R. Peattie.

Peattie, Robert Burns. “The Story of Robert Burns Peattie.” Unpublished memoir, 1929. Lent by Mark R. Peattie.

———. “The Story of Robert Burns Peattie.” Unpublished memoir, 1929. Edited and Annotated by Mark R. Peattie, Noel R. Peattie, Alice R. Peattie. Lent by Mark R. Peattie.

Rayne, Mrs. M. L. What Can a Woman Do, Or, Her Position in the Business and Literary World. Petersburg, NY: Eagle Publishing, 1893.

Rascoe, Burton. Before I Forget. New York: Literary Guild of America, 1937.

Sandburg, Carl. “Chicago.” The Norton Anthology of Poetry. Ed. Alexander W. Allison et al. New York: Norton, 1975. 963-64.

Sayre, Robert F. “The Proper Study: Autobiographies in American Studies.” The American Autobiography: A Collection of Critical Essays. Ed. Albert E. Stone. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1981. 11-30.

Sinclair, Upton. The Jungle. 1906. New York: The New American Library, 1980.

Smith, Sidonie. “Constructing Truth in Lying Mouths: Truthtelling in Women’s Autobiography.” Women and Autobiography. Ed. Martine Watson Brownley and Allison B. Kimmich. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, 1999. 33-52.

Stone, Albert E. “Introduction: American Autobiographies as Individual Stories and Cultural Narratives.” The American Autobiography: A Collection of Critical Essays. Ed. Albert E. Stone. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1981. 1-9.

Stover, Johnnie M. “Nineteenth-Century African American Women’s Autobiography as Social Discourse: The Example of Harriet Ann Jacobs.” College English 66.2 (2003): 133-54.

Tompkins, Jane. Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790-1860. New York: Oxford UP, 1985.

Weiner, Lynn Y. From Working Girl to Working Mother: The Female Labor Force in the United States, 1820-1980. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1985.

Welter, Barbara. Dimity Convictions: The American Woman in the Nineteenth Century. Athens: Ohio UP, 1976.

Wertheimer, Barbara Mayer. We Were There: The Story of Working Women in America. New York: Pantheon Books, 1977.

Chapter I

The boys want their father and myself to write our memoirs. They are sensible men in other regards, but in this they seem foolish enough, and anyway, "memoirs" is too impressive a word. I can recall many episodes in my life, but the years and months, the weeks and days stretch away illimitable, little blue-grey waves, with sun here and shadow there, and wind blowing, and are lost on the shores of forgetfulness.

I was born in Kalamazoo, January 15th, 1862 of a beautiful and docile young mother whose husband was at the front in that War Between the States which now seems so incredible. I have an ambrotype of myself at two, a smiling, round-faced mite with straight hair on a rotund head beside my luscious-looking mother, and with gold armlets looping back the sleeves of my frock. The first thing I remember is a red wagon. It was a tiny one and I was drawing it and feeling as if I were floating. My mother, when I told her this, said she did not remember that I ever had a red wagon. Perhaps it wasn't mine. Maybe it belonged to some other child and I had it only for that floating moment. Anyway, it is the first thing I remember.

While my father was at the war, mother and I lived with my grandmother. Grandmother Cahill used to tell me some interesting stories about our relatives. Her father, John P. Marsh, had been a merchant in Burlington, Vermont, and had owned a share in some importing ships. One of his brothers, having caught the migratory germ, decided to go West; he thought of settling in Ohio. Along with him went a young nephew who was recuperating from typhoid fever. This convalescent had a way of falling asleep at odd times and in queer places, and it happened that when his uncle was ready to go ashore at Cleveland, the boy was nowhere to be found. Passengers and crew united in an unavailing search for him. The uncle could not proceed without his charge. Luggage was thrown back on board and the ship went on its way. Later, the unconscious boy was found inside a coil of cable, enjoying one of his naps, and that is how it happened that the Marshes settled in Michigan.

My grandmother, Maria Marsh, was a girl of twelve when she, in course of time, stepped off the boat at Detroit, and as she tripped down the gangplank—she always had an eager step—a grave young Virginian who had but recently come to the Midwest, remarked to a friend: "I'd like to marry that girl when she grows up." He was Abram Cahill and he married someone else in the meantime. This lady died, and after a proper interval, he presented himself to Miss Maria Marsh. [...] Abram, certainly, was not the best man in the world. He had a frightful temper and regarded himself with exaggerated respect. Once, when the young bride with experimental fingers, touched his forehead and said: "I love you," he flashed a forbidding look at her. "Never say that again," he warned, "or I shall hate you."

Maria addressed her husband as "Mr. Cahill," even in the intimacy of their chamber. Or perhaps there was no intimacy. There were six children, it is true, and Mr. Cahill was a stern, yet self-complacent father. Grandmother told me a story of how he once came to the house for a midday meal, found it not yet ready, and going into her bedroom snatched from a bureau drawer the baby clothes she had made, washed and ironed for an expected arrival, and throwing them on the floor trampled them with his muddy boots. To my passionate protests that I would have left him then and there and forever, she smiled with a patient pride. "He was very much looked up to," she said. "He was a man among men." "A brute among brutes," I started to say, but I saw that would be blasphemous and discontinued my criticisms of Mr. Cahill. His son, my beloved Uncle Edward, had a touch of this temper, but he learned to hold it well into hand. He could not be unjust long, and he had a spirited wife who saw no reason why she should be railed at.

Her respect and admiration for her relatives was great. She was one of a family of seven and some of them had made their mark, personally, or by means of marriage. Her next younger sister, Mrs. J. Adams Allen, wife of the distinguished physician of that name, for more than a generation, President of Rush Medical College, was an imposing woman with no little savoir faire, who held a high place in Chicago society at that time. George Marsh and his East Indian born wife, daughter of the celebrated missionaries, [the] Barkers, were also well-known and admired. Then there was Dr. Wells Marsh and Professor Fletcher Marsh and their families.

I had one ancestress who came to Michigan at the time of the migration of the Ransoms and Marshes. Her husband took up a government claim and settled in the wilderness, made a clearing, built a house and expected to become a successful farmer. Then he fell victim to pneumonia and died leaving his wife with eleven children. [...] Upon the death of her husband she let out portions of his grant to farmers who worked it on shares. [...] The children grew up to take a respected place in the early life of Michigan. The fact of one can be seen on the walls of the Supreme Court rooms in the State House at Lansing, Michigan. He bore the impressive name of Epaphroditus. [2]

My grandmother used, on occasion, to act as hostess at the Executive Mansion during the administration of Epaphroditus and she had told me how, at a certain dinner party, wine was served, to her surprise and outrage. When her glass was filled, she lifted it and said: "Is this mine to do with as I please?" "Yours," said the governor, "to do with as you please." "Then," said Maria, "this is what I please to do with it," and she threw it out the window. Even at a very young age, I was unable to think of this as an exhibition of good manners. [...]

Charles Marsh, as brother of my grandmother, was one of the early physicians of Michigan, practicing chiefly among country folk. He was much in favor with the Dutch at Holland Prairie where my grandfather Cahill had had his farm [...] he was a musician as well and could extemporize with the beauty and fervor which held in rapt those who heard him. Music ran in the family. Grandmother and great-grandmother were singers themselves and had singing families. Many a harsh and jangling moment was dissipated by song; even the most sullen child, it appeared, had to yield to its influence. My mother had a rich and lovely mezzo-soprano [voice], but not one of her children could sing. They were tuneless and none of them, save myself, has been interested in fine music.

One of my grandmother's finest virtues was her active interest in the education of the young [...] there was seldom a time when she did not have some young person living with her for his or her "board and keep" that school could be attended. [...] One of her particular friends was Lucy Stone, [3] one of the first educators of women in the Midwest. This was Mrs. Abram Cahill, a widow with six children, and of New England descent.

My mother, however, had little education. Her heart and mind were bound up in her mother's heavy domestic burdens. She was maternal to the core of her [being] and literally could not concentrate upon anything so abstract as lessons while the concrete in life was demanding her attention. So she was her mother's "dear, good daughter," and she became a dear good mother. My mother was the eldest child of her mother and was named Amanda Maria Cahill. She called me Elia after her mother's youngest sister.

My Father was Frederick Wilkinson, [4] born in Birmingham, England but brought to this country at the age of six and an American by passionate conviction. My father also had a passion for education, at least in his youth, but he made no effort to give his five daugthers anything more than a primary education. But as a youth, he had an aspring and eager outlook. He worked in a foundry, sawed wood, cared for yards, and swept out stores to pay his way at the University of Michigan. Finally his elder brother, William, left him money enough to continue his studies. This William recieved from the Wilkinson family the admiration and preference which the English accord to the eldest son, and father, who was constitutionally democratic in his convictions, was outraged by this discrimination. [5] There were two sisters, Hannah, a few months younger than my father and his loyal pal, and Sarah. The former became Mrs. Robert Price, the latter, Mrs. Fred Farnsworth. All of these people lived in Ann Arbor. The hills, the woods, the fields and river were integral parts of father's youth. He and his sister Hannah conducted their juvenile explorations there and loved it and each other.

He had attended the University of Michigan for two years and [went] to Kalamazoo to study at the Law School. As a stump speaker, he won a local reputation, and he began well at the bar. While he was at Law School, he met my mother. She was engaged at that time to a Canadian gentleman named Wilson but there leaped up a flame of love between Frederick and Amanda and she wrote to the other man asking his release. Mr. Wilson—who was a maker of carriage bodies, replied with magnanimity: "To thine own self be true, and it will follow as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man." [6]

The finding of gold at Pike's Peak delayed the marriage of Frederick and Amanda. He was a poor man and wanted money; also, he was a restless man and wanted adventure. He joined a prairie caravan and traveled three months across the plains, sleeping at night with his musket at his hand, riding by day on his horse, and performing his share of the labors of march and camp. At no time, as it happened, did they encounter any hostile Indians; buffalo they saw by the thousand. He told of being wakened early in the morning by the pounding of hoofs, of springing to his feet and catching sight of the Pony Express as horse and rider thundered by.

"What news?" shouted father.

"Lincoln's elected," came back the answering shout.

I do not know how many months father remained at Pike's Peak, but it was long enough for his vivid personality to make an impression upon his associates; he was sent as one of the delegates to Denver from the territorial legislature. He made no dramatic lucky strike at the diggings, but he was a couple of thousand dollars to the good when Old Abe's first call for troops drove all idea of personal gain out of his head. With a company of men, he started back across the plains. Women and children did not accompany this train. Oxen, which had set the pace for the outgoing company, were left behind. It was a company of great-hearted gentlemen in rough clothes, fired with a determination to live in a country guiltless of slavery, and free from an idle and arrogant aristocracy, that sent them hastening back to the states that had nurtured them, to enlist for war.

There were goodbyes to father's mother and sisters, then, the visit to his sweetheart, the sudden, almost unpremeditated marriage, three weeks of fitful, emotional happiness at the recruiting station at Detroit, and then away to the hard campaign, to more than three years of bitter home-longing, of danger, sickness, wounds, hardship.[...] My father came home from the war quite broken in health, in the care of a colored boy named Thornton Holmes who pawned my father's sword and sash to pay for food on the way home. So we had as souvenirs only his cartridge belt and his cap with the company letter K shot way.

Father had what we have now learned to call "shell shock" and for three months hardly slept at all but lay and sobbed: "The battle fields! The battle fields!" He was a man who shrank from killing anything. They said he had been a red-cheeked, eager young man, more apt to be running than walking, but he came back from the war tense, nervous, often irritable and given to argument. [He was] a changed man. In some ways, a bitter man, often a tender one; yet, on slight provocation, an irritable one.

Then there was Uncle Edward Cahill, my mother's elder brother, who also had been through the war, and came back from the war slender and gay. He snatched me up and tossed my in the air. "So this is little E. Wick!" he cried. He called me E. Wick to the end of his days. [...] He married Lucy Crawford, the daughter of an old-fashioned school-master, dictatorial as a Hohenzollern, [7] but a fine man for all that.

Father and Uncle Edward Cahill, who also had been admitted to the bar, moved to St. Johns, Michigan, a little town surrounded by heavy forests, with nothing particular to recommend it. Father bought a block of land and, in the midst of it, built a modest wooden house which was to be, eventually, an adjunct to a grand, square brick mansion. The Lombardy poplars he set out on each side of the driveway grew rapidly and, to my childish eyes, looked very imposing. There were ornamental trees over half the property and fruit trees over the rest, with a kitchen garden, and wheat or corn or buckwheat were planted in among the trees. We had a cow and hogs and chickens, drew our water from a well and a cistern, and had a woodshed full of odorous pine and oak firewood.

Mother's kitchen had a rag rug on the floor for which she had sewed the rags. There were Boston rockers by the windows and blossoming plants on the window ledges and gay covers on the tables. The sitting room had a what-not with shells, coral and some knickknacks a Missionary named Rose had brought back from India. There was an organ there, and a three-ply capet and lace curtains. Mother's bedroom had a rosewood set in it and looked out on the orchard.

The years when I was growing from babyhood to twelve years of age [1874] are rather blurred. Two boys were born into the family and both died, one soon after birth, the other at twenty-four months. I can still remember this little brother quite well. He was named for father and was a blue-eyed child, smiling and friendly. Father was away on business when the child died and I remember his homecoming—so heart-broken—and mother's broken explanations. Freddie and I had played out in the delusive March sunshine and he had taken his fatal cold. "I thought it was warm enough," poor mother would say over and over again. They buried all that was left of this little laughing boy at the western extremity of our place. The sorrel grew thick there, and I thought it was "sorrow" and was glad it grew there.

Two little sisters came along in time, Gertrude, [8] seven years younger than myself, and Kate [9] two years younger than Gertrude. Father adored Gertrude, partly because she had come after Freddie's death to help heal his grief, and partly because she was so extraordinarily pretty. These sisters were so much younger than myself that, save as responsibilities, they did not much enter into my life for the next few years. They couldn't go berrying in Emmons' woods, or chase butterflies, or go after the cow in the twilight down on the Commons or share my satisfaction in going to Sunday School. Father was superintendent of the Baptist Sunday School and I was the abhorrent pupil who learned the most verses. I would stand up in my figured delaine [10] frock with my copper-toed shoes and speak out loud and clear and feel like a Good Child.

Sometimes my mother's sisters lived with us for a time. There were Jennie and Mary, both with beautiful singing voices and long curls, and there was Lizzie, dark and perverse, who wrung her mother's heart. Jennie became Mrs. Charles Fitch and died young of tuberculosis; Mary became Mrs. John Royce and died of the same disease, leaving three children. Lizzie died unmarried, a wild hawk of a girl with her own sultry secrets. She was the first dead person I ever saw.

I hadn't many friends. We were rather remote on our square of land. Near at hand was a girl older than myself named Edna Bridgman. She had pimples and an aptitude for decoration and she and I loved to make "bowers" of vines and flowers and dress ourselves up. I couldn't think why she was so white—white as the buckwheat blossoms. I admired this pallor very much. We had a great deal to say to each other though I don't know what it was about. She graduated at the head of grammar school and died a month later of anemia and was buried in a bright green dress she had worn on Commencement Day.