Omaha World-Herald Writings

The urbanization of America in the late nineteenth century triggered the expansion of the daily newspaper. Between 1880 and 1900, the population of the United States increased by fifty percent, the national wealth more than doubled, and people began crowding into cities, especially the new urban centers of the Midwest and the West. To attract this new population, newspapers began to change from the genteel, Victorian publications, which catered to the educated, upper classes, to ones that appealed to the masses. Joseph Pulitzer introduced "new journalism" in 1883 when he transformed the New York World into a newspaper targeting the working class. William Randolph Hearst joined the race for readers in 1895 by purchasing the New York Journal from Pulitzer's brother Albert. Soon the Journal surpassed the World in circulation through new journalism's tactics of exciting news, crusading editorials, stunts and self-promotion, extensive illustrations, and colorful cartoon pages–all for a penny a day. [1]

Alarmed by the sensationalism and superficiality of the penny press, the traditional newspapers, which sold for five cents a copy and maintained strong political alliances, attacked the commercialism of the more aggressive newspapers, calling their reporting "yellow journalism," the color associated with "end-of-the-century decadence" and "urban social decay." [2] However, by satisfying the popular taste for crime and scandal, by exposing people of wealth and power, and by "ignoring social conventions and cultural taboos," both Pulitzer and Hearst built huge media empires. [3]

Journalists at the end of the nineteenth century scurried to catch their readers' attentions during this time when the mass market of newspapers proliferated within an increasingly educated and conspicuously consumer-oriented society. Many term this era the "Age of the Reporter," for editors needed thousands of words daily to fill up their pages. News gathering moved to the forefront, and reporters increasingly earned higher salaries with popular writers gaining bylines. [4] In an attempt to lure readers, journalists strayed from traditional reporting to innovative writing, today labeled "new journalism," "narrative journalism," or "literary journalism," that borrowed conventions from realistic fiction–adding suspense and emotion to their news stories. Reporters gathered information about people or events and then composed the material in the manner of a story, recreating scenes, developing character, and heightening conflict. These dramatic news accounts pleased the publishers and consumers alike, none particularly concerned with the accuracy of the facts being presented. [5]

The "new journalism" proved a perfect vehicle for Elia Peattie, a poet and short story writer at heart, and she knew what constituted a good story and how much "fiction" to add to attract a large readership. In her memoir Star Wagon, she confessed, "I enjoyed my writing on the paper, and I was given a free hand, putting the fictional touch on most of the things I did and being permitted to sign my articles." Peattie's fictional touch, however, would not have been in subverting the facts of the story but in presenting them in a more narrative form.

Another change in newspaper writing was the violation of the convention of objectivity as journalists foregrounded themselves, openly expressing their viewpoints, prejudices, and emotions and becoming "personalities." In their editorials and feature articles, these writers became state and often national celebrities whose bylines themselves drew readers. [5] Peattie became a name familiar to readers of the Omaha World-Herald, so much so that many of the headlines to her editorials or articles included her name: "Character in Furniture: Mrs. Peattie Tells How Human Nature Crops Out in House Arrangements," "No Need for Prostitution: Mrs. Peattie Refuses to Accept the Claim That the Wanton Is Necessary," "Mrs. Peattie on Lynching: The Blot on the Name of Civilization and Why It is There," and "Of Emerson the Giant: Mrs. Peattie Defends the Literary Memory of the Philosopher of Concord."

As the role and content of newspapers changed, the gender bias did not. The image of the reporter remained that of the rugged male, working in a tobacco stained newsroom "who wore wrinkled clothing and drank scotch." Women were warned away from the demoralizing atmosphere of press clubs and the city room that were no place for a lady. [7] Even women journalists cautioned their own sex: "I seriously advise any cultivated woman determined to only do the finer kind of journalistic work to choose some other mode of bread-winning, if she would not find herself in middle age doomed to hack work and a poverty very close to destitution." For an "average woman" with "ordinary ideals and ambitions," journalism might earn them a "fair livihood." [8]

Making her living by writing and in the public world of men, however, did not threaten Peattie, not only above average but cultivated and with high ideals and ambitions. She adamantly believed that a woman could be "cultivated" and a journalist. In response to a letter about an article she had written, she penned an editorial titled "In Defense of Her Own Sex" where she stood up for her gender and her beliefs. "You think, do you madam, that a wrangle over 'rights' is unseemly? Why, then, so was the American Revolution unseemly; so was the wrangle which secured the manumission of slaves, so has been every struggle for liberty! Unseemly! All vital things are unseemly. To be perfectly respectable one needs have done nothing at all. A sawdust doll, dear madam, is always seemly." [9] Peattie had her own definition of the cultivated woman, for she believed that a woman who did not enlarge her mind with knowledge or strengthen her body by exercise was "no more to be compared to the cultivated woman than the wild plums to the perfect product of the carefully tended orchard." [10] She fulfilled her own ideal of the Uncommon Woman.

References

Faue, Elizabeth. Writing the Wrongs: Eva Valesh and the Rise of Labor Journalism. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2002.

Jackson, Kate. George Newnes and the New Journalism in Britain, 1880-1910: Culture and Profit. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2001.

Kerrane, Kevin and Ben Yagoda. The Art of Fact: A Historical Anthology of Literary Journalism. New York: Scribner, 1997.

Low, Frances H. Press Work for Women, A Text Book for the Young Woman Journalist: What to Write, How to Write It, and Where to Sell It. New York: Scribner's Sons, 1904.

Marzolf, Marion Tuttle. Civilizing Voices: American Press Criticism 1880-1950. New York: Longman, 1991.

Peattie, Elia. "In Defense of Her Own Sex: Mrs. Peattie Writes a Reply to the Communication of A.M.M." (1 Dec. 1895): 24.

———. Star Wagon. Unpublished Manuscript. 1928. Edited and Annotated by Joan Stevenson Falcone.

———. "Word with the Women." Omaha World-Herald (28 September 1895): 8.

Illustrations

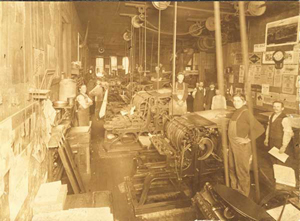

"Klopp Printing 12th and Farnam." Courtesy Omaha Public Library.

"Newsboys." Library of Congress. Group of newsboys at Evening Journal Office. Investigator, Edward F. Brown. Location: Wilmington, Delaware / Photo by Louis [i.e. Lewis] W. Hine, May, 1910. LC-DIG-nclc-03588. (Public Domain.)

Notes