Homes for "Fallen" Women and Girls

Frontier women involved in "feminine works of benevolence" often reached out to their sisters who had turned to prostitution for their support. Rarely was pursuing this avocation a working woman's original goal, but often "limited employment opportunities and underemployment drove thousands of poor women in cities to turn to prostitution to survive." [1] Those most at risk, according to historians, were women low on the socioeconomic ladder, such as domestic servants who could be fired by their employers at a moment's notice, along with seasonal workers and underpaid factory laborers. [2] Also at high risk were young girls whose parents had died. William Sanger, who conducted a study of prostitutes in 1858, found that over half of the two thousand "soiled doves" he followed were, in fact, orphans. [3] Sometimes women decided to try prostitution in order to escape relationships of abuse, emotional depravation, or alcoholism. Others, especially girls who lived away from their relatives, decided to try it, speculating that their standard of living would be higher because of the additional income prostitution might bring–or that their lives might be more exciting than the drudgery of farm labor. Rarely, however, were their expectations fulfilled. [4]

Prostitution flourished in growing cities of trade, such as Omaha, and in Western mining towns where the gender imbalance was significant. During the years of depression in the 1890s, prostitution in Omaha increased as "saloons, brothels catering to all classes of men, and cribs proliferated in Omaha's vice district." [5] Josie Washburn, a prostitute in Omaha during this era who later became a brothel owner, described in her journal the effects of the "soiled dove" lifestyle upon a woman: "After a year of this life the prostitute turns into one of three channels, either becomes a tough, hardened creature who is always ready to take part in every kind of depravity, or is stupefied with dope, lovers and more dope. Or else she is awakened to the horrors of her plight and makes every effort to extricate herself therefrom." [6]

As prostitution increased, the campaigns to contain it also became stronger. Historian Glenda Riley explains that "as towns grew in size and importance, there was usually an accompanying movement to reduce or repress prostitution within their boundaries." Ordinances and fines were put in place in an effort to curtail the practice, although at times these fees seemed simply a business expense. [7] Typically, police collected "five dollars for each madam and one dollar for each prostitute daily" during monthly raids. [8]

Homes for "fallen women" were also established to assist prostitutes who wished to escape the industry and establish new lifestyles. Peattie publicized the efforts and also the needs of several such homes in her columns. Of the House of the Good Shepherd, Peattie wrote, "no sinner is so abject that she may not there find friendship, shelter, welcome, and have pointed out to her the way of salvation." [9] The institution took in seventy women whom they housed, ministered to, and trained to be "needlewomen" although the ladies gladly did laundry or any kind of domestic labor they could find.

In 1893 the Mission of Our Merciful Savior was opened in Omaha to mixed reception. Peattie was saddened and outraged by the community's ambivalent support of the Mission and spoke to the hypocrisy of public sentiment in her column: "The opening of the mission was received . . . by others with lukewarmness and skepticism as to results, and by others still with absolute indifference if not actual hostility, on the ground that it was sheer waste of time and good money to do anything to reform fallen women . . . the hardest person to understand is the unsympathetic, Christian woman, who absolutely refuses to lift her finger, to speak a kind word of hopeful encouragement, or to give one single cent to any honest effort to recall, or to save a fallen woman . . . though it were, perhaps, her son or her own husband, at some time in his life, that had betrayed and ruined her . . . ." [10]

The establishment was run by two Catholic nuns, one named Mother Caroline, who willingly opened their records and financial books to the journalist. Mrs. Peattie, having chastened the community for not supporting the Mission of Our Merciful Savior, whole-heartedly included a full copy of their financials in her column, as if to further demonstrate the integrity of the institution.

Read Peattie's Writings

References

Armitage, Susan and Elizabeth Jameson. The Women's West. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

Bloomfield, Susanne George. Impertinences: Selected Writings of Elia Peattie, a Journalist of the Gilded Age. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Hellerstein, Erna Olafson, Hume, Leslie Parker, and Offen, Karen, eds. Victorian Women: A Documentary Account of Women's Lives in Nineteenth-Century England, France, and the United States. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1981.

Riley, Glenda. The Female Frontier: A Comparative View of Women on the Prairie and Plains. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1988.

Rosen, Ruth. The Lost Sisterhood: Prostitution in America, 1900-1918. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982.

Washburn, Josie. The Underworld Sewer: A Prostitute Reflects on Life in the Trade, 1871-1909. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

Illustrations

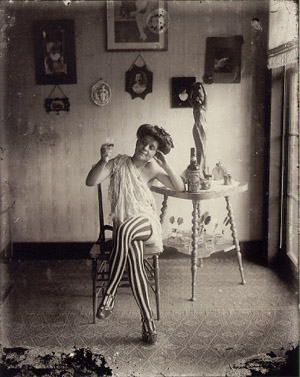

"Untitled." E.J. Bellocq. From the estate of E.J. Bellocq and Lee Friedlander. Courtesy of Master of Photography, http://masters-of-photography.com/B/bellocq/bellocq_photo1_full.html.

Notes

XML: ep.owh.cha.0002.xml