Elia Peattie's Journey to Wonderland

When Elia and Robert Peattie, their children, and Elia's mother-in-law moved to Omaha to begin their work on the Omaha World-Herald, one of their first neighbors happened to be John Hyde, who had just published the third and fourth travel guides for the Northern Pacific Railroad. Although the first two, The Wonderland of the World (1884) and The Wonderland Route to the Pacific Coast (1885) were written anonymously, Hyde claimed authorship of Wonderland; or Alaska and the Inland Passage, by Lieut. Frederick Schwatka, (1886) and Wonderland, or, The Pacific Northwest and Alaska (1888). Aware that Peattie was a well-known author, he suggested that she might like to write the next in the series. He gave her a letter of introduction to the passenger superintendent (presumably Olin D. Wheeler) of the Northwestern Railroad, a company that had not only established a line from Minneapolis to Seattle and Tacoma but that also owned a steamship line to Alaska, so that she might contact him about the project.

Soon after, Peattie departed for Chicago to stay with her family and nurse her children through the whooping cough, for the doctor had prescribed a change in climate for their recovery. Once they had recuperated, she travelled to Minneapolis for her interview and, "mysteriously, was given the commission to write the guide book." [1] Back in Chicago, she purchased what she would need for her trip, picked up her children, and returned to Omaha. While the children stayed behind with Robert, his mother, and a "good domestic," she began her adventure to Wonderland in the early fall of 1889, courtesy of the Northern Pacific. Not only did the railroad pay Peattie for her narrative, but it also covered her $175.00 transcontinental and "Alaska Excursion" fare as well as her expenses.

Peattie's mission was to describe her journey as well as gather information about the major towns on the Northern Pacific route. She usually began by visiting the Chamber of Commerce, who would connect her with a leading citizen to act as her guide, showing her the sights and giving her facts and statistics about the municipality. Ordinarily she could "do" a town in twenty-four hours, but sometimes she managed to double up, creatively hopping a freight, making friends with the men in the caboose, and listening to their stories until the next stop.

History of the Transcontinental Railroads

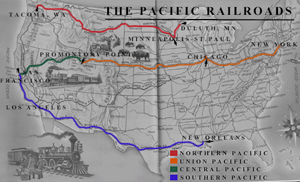

The settlement of the frontier began with journeys to the West by early explorers, which often followed established Indian trails, and gained national exposure with the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804 to 1806. Overland routes, such as the Oregon, Mormon, California, and Santa Fe Trails, did not begin until the Bidwell-Bartleson party, comprised of one hundred farmers and their families, trekked to California and Oregon in 1841. Western trails ultimately carried up to a half of a million emigrants to Oregon, California, Colorado, Utah, and Montana from the 1840s through the Civil War, dwindling to a trickle with the building of the transcontinental railroads. With the joining of the Central and Union Pacific railroads in 1869, settlers could now make the journey from Omaha to the Pacific Ocean in approximately two weeks. However, families who couldn't afford the price of railway fares for their family and their belongings still traversed the Oregon Trail in covered wagons through the 1880s and even up to 1912. [2]

With the tremendous interest in western settlement, President Abraham Lincoln authorized the Pacific Railway Act in 1862 to aid in the Construction of a railroad and telegraph line from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean along the 32nd parallel. The government gave away huge grants of land for rights-of-way and approved two railway companies, the Central Pacific from the east and the Union Pacific from the west, to participate in the development of the transcontinental railroad. Each company was given ten square miles of public land on alternating sides of the track for every mile of track they laid (except across rivers or through towns) to sell to finance the building of the railroad. Although they made huge profits on the land, even this was not enough, and the railroads had to lure investors as well as settlers, offering almost 100 million dollars worth of stock to potential shareholders. Construction began on both sides of the continent in 1863, and on May 10, 1869, the lines met at Promontory Summit, Utah, for the driving of the golden spike, uniting the continent.

Congress ultimately granted 774 million acres of public land for rights-of-way for various railroads. One of these was the Northern Pacific Railroad, created by an Act of Congress in 1864 and chartered to construct a line from the Great Lakes to Puget Sound, following the route of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Construction began in the east near Carleton, Minnesota, and in the west at Kalama, Washington Territory, in 1870. However, by 1873 the eastern segment had extended only to Bismarck, Dakota Territory, and the western portion to Tacoma, Washington Territory. Although the railroad had acquired over 47 million acres along the route, the company ran out of funds when they were unable to sell sufficient bonds to cover expenses. Overextended, the bond sellers went bankrupt, helping create the banking panic of 1873. Finally in 1878, several eastern businessmen reorganized the railroad, streamlined its finances, and sold more than forty million dollars in bonds. The Northern Pacific was on the move again. On August 23, 1883, after nearly twenty years of tunneling through mountains (one nearly a mile long), crossing passes, and spanning rivers, the crew drove the final spike at Gold Creek, Montana Territory.

Almost as soon as the Northern Pacific completed its original line, it began construction of a vast system of branch lines between 1888 and 1893, driving it into a second bankruptcy during another economic depression. However, James T. Hill, who organized the Great Northern Railway, through a series of stock-market maneuvers, gained control of the Northern Pacific, making it a stable investment.

Promotional Travel Literature

Because of the great sums of money needed to finance the railroads, one of the major concerns of the companies was advertisement to attract settlers to buy their lands and then freight their belongings to their new homes, to entice investors to buy their bonds, and to lure tourist to buy tickets to travel their lines. "The railroads marketed each region along their lines . . . often exaggerating or distorting the truth about the territory in order to make it more appealing." [3] Once a region became populated, the railroads would profit enormously, supplying needed goods to the new settlements in the West and then shipping produce and natural resources back to the East. However, since part of the land along the systems was too rugged for settlement, the railroads decided to sell the scenery.

Two types of publications began to appear to fuel this western movement: railway guides and travel guides. Railway guides aided in the logistics of travel, containing maps, lists of stations and agents, and, most important, time tables for communities across the United States. The railroads had established standard times for their schedules, but calculating arrival, departure, and connecting times according to complicated charts was extremely confusing. Moreover, many communities still established their own local time until the government created Standard Time Zones in 1918.

Travel guides, on the other hand, bursting with maps and illustrations, served to acquaint travelers with important points of interest as well as help them pass the hours en route. No longer concerned with physically following the correct path over uncharted terrain, travelers wanted information and interpretation of the scenes and settlements rolling by their windows. These guides, usually first hand accounts, often became best-sellers for "armchair adventurers." Some of the first and most famous guidebooks were Henry Williams' The Pacific Tourist: Williams' Illustrated Trans-Continental Guide of Travel, from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean (1877) and George Crofutt's The Great Trans-Continental Tourist's Guide (1870) and Crofutt's New Overland Tourist, and Pacific Coast Guide over the Union, Central and Southern Pacific Railroads, Their Branches and Connections, by Rail, Water and Stage (1878-1879). The latter boasted of one hundred illustrations and was revised and enlarged regularly until 1892. Similar first-person narratives, written by popular authors of the day, appeared in prestigious magazines and newspapers like Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Scribner's Magazine, The Overland Monthly, the New York Times, and the New York Tribune. [4]

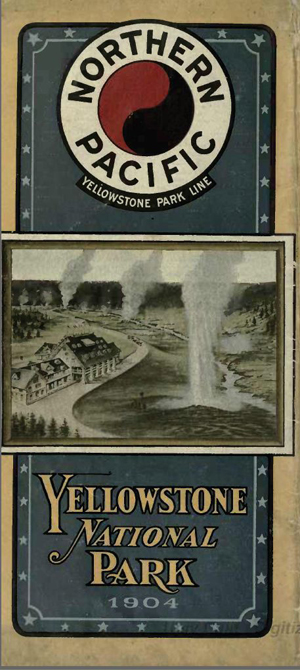

The Northern Pacific Railway, which began its service to Yellowstone National Park in 1883, introduced its series of promotional literature with a brochure entitled Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: The Yellowstone National Park (1884). The Northern Pacific soon became known as the Wonderland Route and played a role in creating an identity for the region. In addition to providing luxurious hotels in the wilderness for its passengers, the railway educated tourists about the sights, history, natural resources, and, of course, investment and development opportunities along the way. With the addition of a steamship line to the gold mines in Alaska, even more adventures awaited travelers. Lavishly illustrated, with later volumes inserting color illustrations as well as a four-color map of Yellowstone Park, the publications introduced the paintings of Thomas Moran, sent by the Northern Pacific to Yellowstone in 1871.

Peattie was the first prominent author to compose a Wonderland guide book. Then from 1892 through 1909, Northern Pacific enlisted the skills of Olin D. Wheeler to write and edit their series, a tradition which continued to raise the standard for travel literature. A topographer with John Wesley Powell's Colorado River Survey from 1874 through 1879, Wheeler settled in St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1882 where he worked in advertising until he was hired by Northern Pacific as the chief passenger agent until his retirement in 1909. [6] Highlights of the series include a history of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, which he personally researched, and the 1900 edition of Wonderland, which opened with a 76-page history of the Lewis and Clark expedition, whose route he travelled and which, coincidentally, paralleled the Northern Pacific rail line. He later expanded this to a two-volume, 800-page history, The Trail of Lewis and Clark, published in 1904 with G.P. Putnam's Sons for the centennial of this expedition. [7] In all, the Wonderland series totaled 26 issues. Their advertising paid off dramatically. In 1880 the population of the Northwest numbered around 280,000 and by 1910 had increased to 2,257,000. [8]

Yosemite and Yellowstone

The promotion of Western scenery by railroads led to the idea of America's National Park system, although the underlying purpose was profit driven, not the preservation of natural resources. Railroads encouraged Americans to forgo the fashionable European Grand Tour and to discover the Western wonders of Yosemite and Yellowstone that they advertised as rivaling the antiquities of the Old World. In his guidebook, Crofutt encouraged his readers to "Leave your old self behind, . . . keep your eyes and your minds open . . . Lay aside all prejudices, and for once be natural while amongst nature's loveliest and grandest creations . . . Above all, forget everything but the journey." [9]

The sublimity of the rugged mountain peaks, the precipitous gorges, the towering sequoias, and the grotesqueries of spouting geysers and boiling mud pots held a primal attraction for Americans whose beliefs were still defined by the Romantic movement's spiritual relationship with nature and intensely personal search for new experiences. The introduction of Pullman sleepers, dining cars, palace cars, church cars, and even special cars with servants for large parties made the journey agreeable, and features such as travel agents, package tours, luxury hotels as well as tent cities, sporting parties, and dude ranches created a demand for services that made tourism big business.

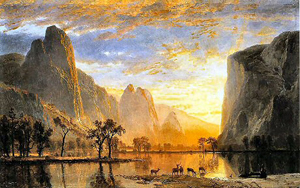

The Yosemite Valley in California was an accidental discovery by the military while forcibly removing the native peoples to a reservation. It did not take long for entrepreneurs to see the economic potential in such a landscape. James Mason Hutchings, a luckless gold miner who first entered the region, commissioned Thomas Ayers in 1855 to sketch the magnificent features of the area, and he published them in California, a promotional magazine he created to attract visitors to his future resort. The 3,000 mile journey by stagecoach across the United States, however, daunted many travelers, but by the 1860s when the Union Pacific began searching for investors, Yosemite became the carrot to entice them. The railroad hired Albert Bierstadt, an already famous artist, to paint the region, banking on his landscapes to lure wealthy Easterners to invest in the railroad. Meanwhile, concerned Californians feared that Yosemite would become another over-commercialized Niagara Falls, and they persuaded Congress to remove the land from the public domain.

The Union Pacific may have had Yosemite, but the Northern Pacific had Yellowstone. Noting the success of Yosemite in stimulating railroad investment, the Northern Pacific profited from their competition's experience, especially their advertising strategies. When surveyors confirmed that the region was devoid of any economic assets, the company went ahead to secure federal protection for the land, of course allowing the railroad to establish hotels within it and build a line to its boundary. Although both Montana and Wyoming territories claimed rights to the park, and the boundaries of the treaty granting the area to the Sioux had to be redrawn, Congress designated Yellowstone a National Park in 1872. Jay Cooke, the head of a Philadelphia banking house and financier of the Northern Pacific, launched a comprehensive publicity campaign, hiring Nathaniel Langford, author and lecturer, Jay Moran, painter, and William Jackson, landscape photographer, to produce promotional material. Moran's celebrated watercolors, engravings, etchings, and oil paintings helped convince Congress to establish a National Park system, encouraged the conservation of America's natural beauty, aided in Western development, and inaugurated a national art in America. [10]

The railroad commenced construction of posh hotels in the Yellowstone area in 1886 with log cabin style architecture and decorations using bearskin rugs, wagon wheels, and quarried stone. However, until the mid-1890s, only the wealthy could afford to visit Yosemite or Yellowstone, so the railroads lowered the fares and began a mass marketing plan to appeal to a wider audience, building outdoor camps alongside plush hotels. The campaigns sold the popular notions of the Wild West romanticized in dime novels and by Buffalo Bill and capitalized on the popularity of Theodore's Roosevelt's interest in big game hunting and wilderness exploration. Yellowstone became "a sportsman's paradise and a camper's dream." [11] The West now had something to offer everyone.

The Angel in the Pullman

Along with passengers, the railroads also transported the social, cultural, and political ideals of the Gilded Age to the remote corners of the territories. Nowhere was this more visible than on the trains themselves. A large proportion of railroad passengers were women, and their letters, diaries, and journals as well as their published writings played an important role in the growth of the western tourist industry.

Whereas the engine was associated with manly technology, the luxurious surroundings of the parlor and Pullman cars bespoke feminine grace. Such domestic surroundings, it was believed, fostered gentility and respectability, allowing women to experience "a new sense of adventure and a new freedom of movement, as well as a new means of security, in travelling through the West." [12] The trains functioned as a sort of microcosm of society wherein the Victorian lady could create a "'public domesticity'–a social ideal that was neither as private as a home, nor as socially unruly as a public street." Simply through her presence, a woman would "bring the cultural associations and behaviors of home life to bear upon social interactions among strangers, to regulate public interactions and delineate the boundary of Victorian respectability." Advice books, like John A. Ruth's Decorum: A Practical Treatise on Etiquette and Dress of the Best American Society (1880) reinforced the rules of good manners and contained a special section on train etiquette. Thus, having women passengers on the trains transformed them into moral, and therefore acceptable, public spheres where men were gentlemen and women were ladies, and it was safe to bring one's children. [13] Many travel guides picture women and daughters, unescorted, enjoying a vacation together.

By the 1890s, however, gender boundaries were being renegotiated with the shift of the population from the country to the city, the rise of the middle class, and the emergence of the New Woman. Again, the railroad car mirrored this new social order with the increasing numbers of middle class tourists sharing the large coaches. The mixture of classes and cultures fostered a democratic spirit of togetherness and promoted interaction among the passengers as they escaped from the anxieties of the rapidly industrializing world into nature. This, however, allowed for a new sort of freedom. "Set free from the watchful eyes of small communities, uncertain of the identities and status of those around them, passengers often flouted the rules of conduct." [14] The train became the setting in many railroad promotions for a place for couples to meet and, perhaps, to fall in love. Travel brochures pictured women, vital and unrestrained, climbing mountains, riding horses, shooting wild game, playing sports, and building campfires, activities not traditionally accepted back home in the parlor.

Peattie's Liberating Experience

Peattie enjoyed the same sense of freedom riding the rails that other women of her era experienced, calling her railroad journey to Tacoma and her voyage on the Elder to Alaska "a very liberating experience." Travel by train was nothing new to her, but she usually had her family along, or she was traveling for business. She explained in her memoir "Star Wagon" that "For the first time in my life I was free of house-keeping trammels. I felt a zest beyond description." She recounts many stories of the people she met as well as the stories that they told her, declaring, "The passengers on the boat were friendly, widely traveled, of many places and kinds of culture." She shared her cabin with Miss Sarah Hall, "a tall, modest, yet confident, comely, intelligent Englishwoman" who was taking three years to travel alone around the world and had already been involved in three shipwrecks. Peattie returned home, "richer in experience, with my mind filled with splendid pictures." The people she met, the stories they told her, the places she visited, and the adventures she experienced profoundly affected her life and her writings, investing them with a richness that only comes from living fully.

Upon returning home to Omaha, Peattie began organizing her notes and drafts for her travel book. Looking at the conglomeration of facts and statistics she was required to include in her narrative, she must have wondered how she could possibly make the reading compelling. A storyteller at heart, she decided to make her travel guide a sort of novelette, and invented the very American Scott Key as her protagonist. To add conflict, she gave him a broken heart and made him a stuffy New Yorker going west on business. Determined to be miserable, he was unimpressed with Niagara Falls and uncommunicative on board the train. However, as he meets more and more people, the characteristic "types" one meets on any excursion, he loses his morbidity, and he finally becomes a part of the little community in the passenger car. Peattie introduces the "statistical" and "too good-natured" lumberman (perhaps modeled after her good friend Kate Cleary's husband, a lumberman from Hubbell, Nebraska), who gives Key information about the towns they pass; the sportsman dressed from top to bottom in corduroy and "laden with a most remarkable quantity of fishing tackle and gun-cases," who partakes in all of the outdoor activities along the route; and the rosy and self-sufficient Miss Dinsmore, who shocks him with her impropriety, "for in the East young ladies do not ask strange young men to sit down and talk with them, on the score of an acquaintance extending over the period of ten seconds." Throughout the journey, Key becomes more and more impressed with what the West has to offer, although he still remains restrained. "Impulsiveness is a characteristic of the Wild West. In the East we temper our enthusiasm with discretion."

As Scott settles down to enjoy the journey, Peattie adds a blatant plug for Northern Pacific's accommodations. "I was ready to devote myself to pleasure . . . so I had a consciousness that I would sleep in a well-made bed, have well-cooked meals, carefully served, and the privilege of lolling all day in softly upholstered seats." Nor does she miss a chance to let her political views be voiced through the character of Miss Dinsmore. "It is very pathetic," states the young woman as she gazes at the changes in the Missouri valley. "The Indian has gone, and the buffalo; and the bear and beaver are all but gone. We turned the corn-fields of the Indian into battle-grounds. Civilization must go on, I suppose, but it is rather hard that the Indians must always be the victim of it."

Eventually Scott succumbs to the democratic spirit on the train and begins enjoying his companions, even attending the wedding of Miss Dinsmore and a Dakota rancher. As the miles roll by, and Scott visits more westerns cities, he is transformed by the "wonderful buoyancy of the West." By the time he reaches Tacoma, he forgets his broken heart when he sees the sister of an attorney he is supposed to meet: "The sea-winds had been taking liberties with this young woman's hair . . .she was so full of animal life that it made one eager for action simply to look at her." Impulsively, he declares his love on an Alaskan iceberg while they watch the northern lights. They return together to Tacoma, "the city of destiny," where Scott vows he will remain, "with the lady of my love."

The Northern Pacific Railroad published A Journey Through Wonderland; or The Pacific Northwest and Alaska with A Description of the Country Traversed by the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1890. Peattie manages in ninety-four pages to "do" all of the major towns and sights along the Northern Pacific line, show us the comfort and companionship to be found on such a journey, add her witty interpretations of western scenes and characters, and convince us that a journey through Wonderland is worth taking.

Compared with most travel literature of the time, either first person, first-hand travel narratives or more standard third-person railway guides, Peattie's approach was refreshing. According to Craig Crouch, Northern Pacific Railroad historian, both of the travelogues by John Hyde, the two preceding hers in the Wonderland series, were "straight-up travelogues with no fictional characters." Peattie, however, chose to incorporate fictional characters, conflict, and a plot, albeit it a rather conventional love story, to make the statistics and regional information more palatable, and she was one of the first to do so.

Fictionalizing promotional narratives was rare, and then not well done. The Great Northern Railway's 1885 guidebook features six fictionalized travelers, who decide to form the Happy Travelers Club and choose as their motto "We are the People." The narrator is "Blair Camera, occupation, snap shot." [15] Amy G. Richter in Home on the Rails states that "Beginning in the 1890s railroad brochures increasingly featured fictional images of woman railroad passengers . . ." [16] The most famous fictional character was Phoebe Snow, the creation of Earnest Elmo Calkins. Snow was the spokesperson for the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad from 1900 to 1917. She dressed in pure white linen and spoke in rhyme, praising the ease and cleanliness of the line and personifying Victorian domesticity. Although the character originally promoted streetcars, her image soon graced the pages of magazines and newspapers, appeared on billboards, and even helped sell women's clothing, especially sports attire. Not only was this marketing strategy successful, but Snow also helped promote the image of the healthy and self-sufficient New Woman. Similar strong women characters began appearing in popular magazines and best-selling novels, such as Francis Lynde's A Romance in Transit (1897) and Frank Spearman's Daughter of a Magnate (1903).

Not only does Peattie's A Journey to Wonderland do its job in promoting the Northern Pacific Railroad and the American Northwest, but the narrative strategy is innovative for the genre and the subtext reinforces the strength and capabilities of the emerging New Woman–a role in which Peattie herself moved comfortably.

References

"A Brief Introduction to the Northern Pacific Railway." Northern Pacific Railway Historical Association. 30 March 2008 http://www.nprha.org.

Cooper, Bruce C., ed. Riding the Transcontinental Rails: Overland Travel on the Pacific Railroad, 1865-1881. Philadelphia: Polyglot Press, 2005.

Crouch, Craig. "Re.Wonderland Books." E-mail to the author. 27 April 2008.

Fifer, J. Valerie. American Progress: The Growth of the Transport, Tourist, and Information Industries in the Nineteenth-Century West Seen through the Life and Times of George A. Crofutt Pioneer and Publicist of the Transcontinental Age. Chester, CN: Globe Pequot Press, 1988.

Harvey, Eleanor Jones. "Thomas Moran and the Spirit of Place." Dallas Museum of Art. 21 April 2008 http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/2aa/2aa543.htm.

Johns, Joshua Scott. All Aboard: The Role of Railroads in Protecting, Promoting, and Selling Yellowstone and Yosemite National Parks. 1 August 1996. 30 March 2008. http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA96/RAILROAD.

Mussulman, Joseph A. "Rails to Wonderland." Discovering Lewis and Clark. 1998. 21 April 2008 http://lewis-clark.org/content/content-article.asp?ArticleID=2700.

"The Northern Pacific Railway's Wonderland." 25 March 2008. http://www.sharinghistory.com/RR4.htm.

"Northwest Writing and Regional Identity, Part III: Writing Home, 1850s–." History and Literature of the Pacific Northwest. 19 March 2008. http://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/Website/Hist%20n%20Lit/Part%20Three/Writing%20Home%20Essay.html.

"Oregon Trail Generation." End of the Oregon Trail Interpretative Center. 2008. 13 April 2008. http://www.endoftheoregontrail.org/road2oregon/sa09chrono.html.

Peattie, Elia W. A Journey Through Wonderland; The Pacific Northwest and Alaska with a Description of the Country Traversed by the Northern Pacific Railroad. St. Paul, MN: Northern Pacific Railroad, 1890.

———. "Star Wagon." Unpublished Manuscript. 1928. Edited and Annotated by Joan Stevenson Falcone.

Phillips III, John A. "First of the Northern Transcontinentals: An Overview and Chronology." Northern Pacific Railway. 30 March 2008. http://pw2.netcom/~whstlpnk/first.html.

"Railroad Sponsored Ads and Promotional Material." History and Literature of the Pacific Northwest. 26 February 2008. http://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/Website/Hist%20n%20Lit/Part%20Three/Commentaries/RR%20Promotion%20Comm.html.

Richter, Amy G. Home on the Rails: Women, the Railroad, and the Rise of Public Domesticity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Smalley, Eugene Virgil. History of the Northern Pacific Railroad. New York: Arno Press, 1975.

Illustrations

"Elia and Barbara Peattie." Photo by Michael Timothy Cleary, Cleary Family Scrapbooks.

"Union Pacific Map." Courtesy American Studies Programs, The University of Virginia http://xroads.virginia.edu and Joshua Scott Johns from All Aboard: The Role of Railroads in Protecting, Promoting, and Selling Yellowstone and Yosemite National Parks.

"Wonderland Covers." http://www.sharinghistory.com/RR4.htm. (Public Domain.)

"Tower Falls" by Thomas Moran. http://www.nga.gov/feature/moran/west4.shtm http://www.nga.gov/feedback/webfeedback.shtm. Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

"Valley of the Yosemite." Albert Bierstadt Gallery. http://www.xmission.com/~emailbox/glenda/bierstadt/bierstadt7.html. With Permission.

Notes

XML: ep.nov.jtw.intro.xml