A Journey Through Wonderland.

I pity the man who can travel from Dan to Beersheba, and cry, "'Tis all barren!"

―–Laurence Sterne.

It was the merest chance that took me westward. I had never previously been 500 miles from New York—except, of course, to Europe. Everyone goes to Europe. The chance that made me journey westward was a business one; but other than business reasons made me glad to go.

"If you ever get an ache of the heart," said a young Frenchman whom I once met, "take a long journey. Visit the Indian Ocean, for instance. There, wrapped in a pajama, one lies on deck at night, watching the swaying of the masthead and the twinkling of the stars—the languorous stars of those latitudes. Time, space, and peace are all there is left of life, and the bitterness and weariness melt away from one, and seem to become a part of the mists in the blue distance. Take my word for it, there is nothing like a voyage on some solitary sea to cure the heartache."

Thus, when it came about that business took me to Duluth, to Winnipeg, and St. Paul, I concluded to go farther–across the plains, the mountains, and to Alaska. I substituted Alaska for the Indian seas. Alaska, I confess, seemed a very long way off, for I had not, at that time, learned that distance is no actual quantity, but is determined only by the convenience or inconvenience that attends a journey. When I left my native city, however, the words "Duluth" and "Winnipeg" were without significance to me, and even St. Paul meant little enough.

The first two days are indistinct in my mind. There are circumstances under which a man can not enjoy even a Niagara. I could not hear its roar for the cooing of newly-married lovers, and considering a recent experience of mine, I naturally felt irritated. A few long days on the lakes followed, and I got a certain comfort out of them. It is true that I did not lie wrapped in my pajama while fanned by tropical and perfumed breezes. There were no tropical breezes, for one thing, and I had no pajama. As the oxygen got into my lungs, the morbidity went out of my soul, and I should have been almost happy but for a young lumberman on board. He was a good-natured young man—indeed, he was too good-natured, for he never looked at me without smiling. There was nothing ridiculous about me, of that I was sure. I understood the subject of clothes if any man in New York did, and it was hard for me to find out why a man in a flannel shirt, and a hat at least three years in arrears of the fashion, should laugh at me.

"I should like to see you," he used to remark, "after you have caught the fever."

"What fever?" I anxiously inquired.

"Why, the western fever," he replied. "You will get it, or my name is Dennis."

The phraseology of this young lumberman was not always choice. I was not sorry when I learned that we were approaching Duluth, where I was likely to escape him.

"Duluth," I said to myself, "is no doubt a chilly little harbor with a few lumber mills in the background, and fish-nets straggling on the beach." I had seen a great many dull hamlets of that sort, and I was not interested. To be sure, the young lumberman was buzzing facts in my ear with the pertinacity of a statistical mosquito, but they meant nothing to me.

"It is the largest grain–shipping port in the world," he informed me. "It has a population of 45,000, sir, and its grain elevators have an aggregate capacity of 12,000,000 bushels."

Then he spread his legs apart, and waited for me to be overcome with these facts; but the truth is, I have never been much impressed with figures. But when I saw Duluth rising ledge above ledge, I felt a-sudden thrill of admiration. Southeast of this lay innumerable saw-mills, and their metallic humming came over the water.

"That," said my informant, "is West Superior and Superior City. It is no mean town taken together, even when compared with Duluth. Their population is a little less than half that of Duluth, but they are good towns, sir–good towns. Look at the coal docks, if you please, and you will not be surprised to hear that their coal receipts are over a million tons a year. They communicate with Duluth by the Northern Pacific bridge, you know. But in Duluth is the town, sir! Founded on a rock, with seven railroads, ten banks; with coal, wheat, lumber, steel, railway cars to ship out–"

"My friend," I broke in wearily, "I know all that. I know that in 1870 there was nothing here but a sand-bank. Now I am quite willing to believe that it is the most civilized city on earth. I know also that you western gentle men are accomplished orators."

My lumberman turned to me suddenly, and button-holed me.

"Look here," said he, "if you knew what you were talking about, I should get mad. But I think the time is coming when you will feel different. If the time comes when you have occasion to watch a town grow as I have this, you will know what it is to feel the same sort of pride. I have seen Duluth when she was nothing but sand and rock. Look at her now, sir! Beautiful homes stand on those terraces of trap; 12,500 miles of railroad are directly tributary to her; her taxable property is in the neighborhood of $30,000,000. Of course I am proud of Duluth–as proud as I would be of one of my own children. Never before in the history of the world has it been the privilege of men to watch the growth of cities as they can in the United States in the nineteenth century. And it seems to me, sir, to be one of the great privileges. You may not appreciate it, but I do."

What could I do but give a hearty hand–shake to the enthusiastic lumber-man? In the two days I remained in the cities at the head of Lake Superior, to which I had been introduced with so memorable a eulogy, I experienced none of the lack of comfort and convenience that I had anticipated–indeed, I found conveniences that we in the East had not thought it worth while to provide ourselves with. It was in this town that I met a young man whom I was destined to see more than once in my journey. He was dressed from head to foot in corduroy, and was laden with a most remarkable quantity of fishing-tackle and gun-cases. I was on my way to St. Paul by way of Ashland, thinking it profitable to take that somewhat circuitous route for the sake of seeing that popular resort, when the corduroy-clad individual I speak of sat down opposite me, and loaded three seats with his paraphernalia. I saw that he was fixing a steady gaze on me, but supposing this to be a part of the rudeness I naturally expected to encounter in the West, I paid no attention to it, until at last he broke out with:

"My dear sir, I am sure from your physiognomy that you are a sportsman."

"Then my features belie me," I returned, curtly, "for I have neither the skill to bring down game nor the patience to hold a line."

"But it is impossible to deceive me," he protested. "I know a sportsman when I see one. Your skill may not be developed, and your passion for sport may be latent, but it exists, sir! It exists! And before we part, I hope to prove it to you."

"You are out, then, on a sporting expedition?" I inquired.

"I may say," he returned, crossing his corduroy legs, "that I never go on any other sort of an expedition, and I flatter myself that I have visited many of the most famous resorts of the sportsman in the known world; and I must say I have never found anything finer in the way of trout streams than up here on the north shore of Lake Superior. Gooseberry River, sir, is one of the most extraordinary streams! I caught one trout there that weighed—"

"Pardon me," I interrupted, "but what is your name?"

I gave him my card, bearing a name that I flattered myself was not without patriotic associations—Scott Key. His card, promptly tendered, showed in fine script the honest name of John Parke.

"When your latent capabilities in the way of sporting are developed," continued this amiable gentleman, "you must go to Deerwood. Deerwood is ninety–seven miles west of Duluth. You can get a good hotel over your head at night, and in the day you may wander through one of the most beautiful woods it was ever the privilege of man to set eyes on, and shoot anything worth the shooting, except a Bengal tiger. The deer are superb—and, what is better, they are frequent, so to speak. As for fishing, you can have anything you want. There is pike, sir, and black bass; there is muskallonge, whitefish, pickerel, croppies, sunfish, rock bass, bullheads—"

"I am afraid your eloquence is wasted on me," I protested, "for I do not know one sort of fish from another."

"Well!" pityingly exclaimed Mr. Parke, "I never knew a man who had been so wrested from his natural calling as you, sir. Whenever I look at you, I associate you with a trolling-spoon or a split bamboo rod and a brown hackle.You should go up to the Brule—only 35 miles from Duluth, on the Ashland line of the Northern Pacific—and throw a fly at some of the gamy trout there."

It is unnecessary to repeat more of what this young man said. I seemed to be destined to meet with enthusiasts.

I spent a day in Ashland, a most picturesque little town, the extreme eastern terminus of the Northern Pacific Railroad, lying on the silver Bay of Chequamegon, with the Apostle Islands visible. But although Ashland is a famous summer resort, and has a large hotel bearing the name of the bay, and especially adapted to midsummer tourists, its interest is not simply a romantic one. It is the largest shipping port of iron ore in the United States, and has steel manufactures, among its many other industries, where the ore from the Gogebic range is worked. The Wisconsin Central makes it its terminus. But I cared less for the material advantages than for those odorous forests of pine, those clear streams, and the bay, bright in the sunshine of the late summer.

I took the train to St. Paul, and arriving in that city busied myself with my duties. A man raised in a great metropolis could feel but little interest in so young and experimental a city as that I found myself in. At least this was what I told myself. But I had not been a day in the place before I began to feel some-thing peculiar in the atmosphere. I am referring, so to speak, to the mental atmosphere. The men, for example, seemed to have a strange energy. They walked as if they had something particular to do, and but a very little time to do it in. I began to walk quicker myself, and to look about me with some degree of interest. The buildings, I soon saw, were of a newer and more artistic architecture than that usually seen in American cities.

St. Paul rises in proud terraces from the Mississippi, the first two devoted to business houses, the second two to the homes of the city. A fringe of gentle groves crowns the topmost heights, which bend to the sweep of the river, and here are those houses which I hear have made St. Paul famous in the West as a desirable residence city. I have a theory—not very sound, perhaps, from a commercial stand-point—that the true success of a city is gauged largely by its humane institutions, rather than by its number of bank buildings; though, indeed, the idea is not so far wrong, for it is only the prosperous city that will have hospitals and asylums, since they are only provided for after the jails, the court-houses, and the merchant houses are well established. I found three hospitals, two orphan asylums, and several other charitable establishments. In St. Paul the new county court-house has had a million dollars expended on it—a statement which I did not find it difficult to believe. There are eighteen public school-houses, at which 15,000 children are being educated. All these facts I did not learn at once, nor because I made any especial effort to discover them, but they were thrust upon me by patriotic citizens, and I transcribe them for the benefit of others. Six trunk lines of railroads, from the East, run into this city and through Minneapolis. Indeed, so closely are these two cities wedded, that, in the mind of the stranger, at least, it is difficult to separate one from the other.

"I have always been distressed at the rivalry that some persons have forced into existence between St. Paul and Minneapolis," said a well-known judge, whose office was in one city, and his home in the other. "The time is not far distant when these two cities will be united by a continuous line of suburbs, as they now are by commercial interest. The people of these cities are similar and congenial, and I am opposed to anything that has a tendency to divide them, or pit one against the other."

It was to this amiable old gentleman that I owed much of the pleasure of my stay in these twin cities. He took me to see the wonderful flouring mills of Minneapolis, where I got more flour-dust on my clothes than I could have wished, and where I made little annotations in my memoranda-book, concerning the facts imparted to me by my venerable guide. He told me that St. Paul had 200,000 inhabitants, and Minneapolis 200,001; that Minneapolis was the largest flour market in the world, her mills having a daily aggregate capacity of 37,450 barrels; he said that St. Paul had seven National banks and nine State banks, with an aggregate capital of $7,624,000; and that the manufactured products of Minneapolis for the present year would be over $84,000,000. We had some pleasant rides together, the pleasant old pioneer and I. We visited Fort Snelling, and looked down from its heights at the capricious river which has made the wealth of Minneapolis. We drove to Minnehaha Falls, quoted from the dead familiar poet, to appease his shade, drank beer within sound of the merry little fraud which has stolen the name of the fall that Longfellow designated, and meanwhile the Judge talked to me of his son and daughter who had gone to Tacoma.

"They are the best children in the world," my friend declared, "and you shall carry letters to them. They have gone to make their fortunes in the city of destiny. I never would raise my children to use the money I had given my strength in making. It is the best way in the world to ruin a young man or woman. I am willing to give them a start, but I want them to try their own strength. If you do an arm up in bandages, you can not expect to be able to use it with any execution. It is just the same with young people. I have sent my boy out West, to the best town I could learn of, and his sister has gone along to keep him from being homesick, and to make a home for him. I want you to go up to the house and see them."

From what I have insinuated concerning my state of mind, it can be readily guessed that I was not particularly desirous of an introduction to any lady. I had come West partly to escape the sex, and was somewhat annoyed at finding that they existed even in that part of the world which I had always thought of as essentially a man's country. So I replied:

"I should be very glad to call at the office and see your son, Judge Curtis, but I am not much of a society man. I am sure I should not be justified in intruding upon your daughter."

The old gentleman was not without sensitiveness.

"Just as you please," he returned stiffly. "I will give you a note to my son."

I took the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul train to Lake Minnetonka, one day, and rested at the Hotel St. Louis, from the fatigues consequent upon sight-seeing. Here, amid the many islands, the gentle surprises and the wooded banks of Minnetonka, I could reflect at ease upon these daring and dashing young cities, which had the temerity to outdo many older and more renowned cities in fields which those older cities had esteemed especially their own. I took out my note-book and contemplated it in quiet, with no one to witness my amazement.

Here was mention of one mill that has power to grind 25,000 bushels of wheat every twenty-four hours! Its mighty belts run over its shafts at the rate of 2,664 feet a minute! I laid back on my oars, and dizzily drew in my mind's eye this tremendous flying and whirling, this shifting and grinding! All the power of those twin cities came suddenly to me; I was forced to a realization of their young greatness, their probable future, and I was glad to get back to them, and to walk on their streets at night, mingling with the gay and active crowd that walks under the bright electric illuminations. I dropped into a couple of the attractive theatres, by way of getting rid of solitude, and the next day took a hasty journey from St. Paul to White Bear Lake, an exclusive little resort, where many of the finest suburban residences stand on the shores of a modest and translucent lake.

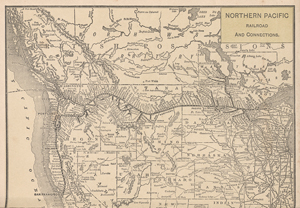

The next day I resumed my westward journey, intending to leave the main road at Winnipeg Junction, 250 miles or more from St. Paul, and then journey north over the Duluth & Manitoba Branch of the Northern Pacific. For 125 miles the road follows the great river, through fields of corn and wheat. Before these are reached, however, the suburban stretch lying between St. Paul and Minneapolis is passed. The imposing fair buildings are to be seen here, a university building, which an agreeable conductor informed me was the Hamline University, and the new shops of the Northern Pacific.

I have all my life been afraid of being bored. I was mortally fearful that now the time of distress was at hand, and that after the entertainment of a cigar had been exhausted, I should have no resources left; for I may as well own at once that I am not one of those fortunate—or fabled—mortals, whose mind to them a kingdom is.

But in a short time we neared Anoka. Now, Anoka is a nice little town of 5,000 inhabitants, engaged in the wholesome occupations of sawing trees into lumber and turning wheat into flour. She is the seat of the county whose namesake she is; but she interested me on none of these accounts particularly. What entertained my fancy was the logging stream, bearing the spiritous name of the Rum River, at the mouth of which she stands. The idea of plenty conveyed in the rushing of that merry little stream, and the recollection of the vast concourse of plunging logs that floated down it—all of which I saw in imagination—with the loggers in the midst, singing and swearing, entertained me while I passed Big Lake and Clear Lake, pretty prairie sheets of water, and reached the shady village of St. Cloud, which, I was informed, had the advantage of Anoka in point of population by 2,000. Granite and jasper are quarried at no great distance from this town.

I was taking careless note of this village, built on its pleasant plateau, when my attention was attracted by the frantic efforts of a lady to open a window. It is one of the banes of my life that women insist on trying to open windows. Either they should go into training and accumulate sufficient strength to successfully accomplish their purpose, or else they should cure themselves of the habit. I have invariably had the misfortune to open windows for jaundiced and dyspeptic ladies, who returned me scant thanks, and did nothing but get cinders in their eyes after the window was opened. However, I did not ring for the porter as I might have done, but, inspired with the spirit of true sacrifice, opened the window for the exhausted lady, whom, to my very great surprise, I discovered to be neither jaundiced nor dyspeptic. On the contrary, she was a rosy and well-dressed young creature, with a degree of self-sufficiency in her manner, and a remarkably candid pair of eyes in her head. I addressed a few ambiguous remarks to her. She smiled at me in a way that seemed to say she understood my embarrassment, and was sorry for me, and frankly asked me to sit down. While this invitation gratified me, it also shocked me, for in the East young ladies do not ask strange young men to sit down and talk with them, on the score of an acquaintance extending over the period of ten seconds. I had read "Daisy Miller," and I must say that, though I in no way approved of that young woman, I was not averse to meeting one of her sort—which I immediately concluded my new friend to be.

"The elms and maples of St. Cloud are very beautiful," remarked Miss Dinsmore—for this, I learned, was her name. I said they were.

"Never so beautiful here, though," she went on, as if continuing her remark without interruption from me, "as in the East."

"Then you are from the East?" I inquired.

"Everyone out here is from the East," sententiously returned Miss Dinsmore, "except a few, whose parents are from the East."

"Then that is why manners are so much more cultivated than I expected to find them," I injudiciously remarked. The candid eyes opened to a some-what embarrassing degree.

"I guess you haven't been out here very long," was all she said, but it had the effect of an accusation, and I felt like blushing. I confessed that I had not.

"Then you are not yet a good American," she said. "We out West here are proud of, and devoted to, the whole of the United States, but you of the East are only devoted to your own little particular place. You must really stay out here, and get your ideas enlarged."

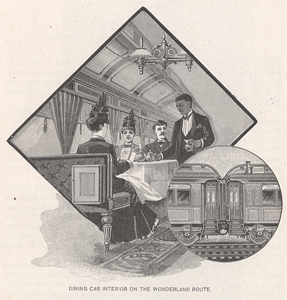

A waiter, with unrivaled elocutionary powers, announced at this point that supper was ready in the dining-car, and that this was the last statement of that fact. Miss Dinsmore started with a promptitude that spoke well for her appetite, and I followed. Now, I am fastidious about my meals. Therefore, I did not look forward with pleasure to the idea of eating on board the train; but whether it was the fact that Miss Dinsmore sugared my tea, and ordered my supper, or that the linen was spotless, and the dishes so well prepared and served, I do not know, but it is certain that I ate far more than usual. In deciding just where the credit is due in this matter, my position is a delicate one; for, while I do not wish to hold back any of the praise I feel to be the right of the cuisine of the Northern Pacific, I can not well, even by insinuation, detract from the share that the lady had in my satisfaction.

While I ate my toast, and defended myself against the intellectual onslaughts of Miss Dinsmore, I looked out on the town of Sauk Rapids, near which lay beds of granite, which my vis-a-vis assured me, with triumph in her tone, was the

equal of any of the boasted granite of New England. When we reached Little Falls, Miss Dinsmore consented to leave the car for a few minutes to pace the platform. I was just casting about for some theme of conversation likely to interest this young woman, when I beheld my corduroy friend—otherwise John Parke, huntsman and angler—bearing down upon us, laden, as usual, to the very bulwarks with traps. He saw me at once, and unburdening himself on the unfortunate conductors and porters, approached me with a cordiality that was only tempered into moderation by the fact that I had a lady with me. He had barely acknowledged the introduction, when he broke into one of his usual rhapsodies.

equal of any of the boasted granite of New England. When we reached Little Falls, Miss Dinsmore consented to leave the car for a few minutes to pace the platform. I was just casting about for some theme of conversation likely to interest this young woman, when I beheld my corduroy friend—otherwise John Parke, huntsman and angler—bearing down upon us, laden, as usual, to the very bulwarks with traps. He saw me at once, and unburdening himself on the unfortunate conductors and porters, approached me with a cordiality that was only tempered into moderation by the fact that I had a lady with me. He had barely acknowledged the introduction, when he broke into one of his usual rhapsodies.

"You've missed the chance of your life," he cried. "I never saw better shooting than there is out here, west of the Mississippi. I've been out here to Rice Lake, and up to my knees in cat-tails and rushes and wild rice, and I've bagged some of the best ducks you ever ate."

"But," interposed Miss Dinsmore, with a certain pathetic intonation, "we have not eaten them."

"Rest easy," said the huntsman, with a gallant salute; "you shall have some of them, for I have brought some aboard, and they are to be cooked for me. I had partridge and grouse, but I gave them away; and I sighted a deer, but, unfortunately, he sighted me at the same time, and our acquaintance ended then and there. I say, Key, if you ever have occasion to put up at the Falls, be sure and go to the 'Antlers.' Everyone who comes out this way gunning stops there, and it is possible to have a jolly time." After this, I seemed to be shut out of the conversation for a time, for the unconscionable hunter walked away with Miss Dinsmore, showing off his handsome legs, in their dashing top-boots and skin-tight trousers, in a way naturally discouraging to a man in commonplace trousers, the ugliness of which were heightened by being a little bagged at the knees. As I could not be amused, I determined to acquire knowledge, and learned that Little Falls possessed one of the best water-powers in the United States, constructed in 1888, and costing $250,000. This is employed for flouring-mills and factories, and by its aid the town of Little Falls aspires to be a manufacturing center in the not far distant future. I also learned that the Little Falls & Dakota Division of the Northern Pacific runs south from this point. This terminates at Morris, eighty-eight miles from Little Falls, and runs through a country distinguished for its agricultural resources, and especially for its remarkable chain of lakes, on which I. judged my corduroy friend had been exercising his privilege of killing. Grey Eagle has a local reputation as a summer resort, as has also Glenwood, which is situated on Lake Minnewaska, a sheet of water, so I was informed, of considerable size and much beauty, which offers fish of many varieties. I meant to do my duty by the country through which I was traveling, and therefore made careful mention of all these facts in my note-book, completing my task just in time to get in my seat as the train moved westward. I found Mr. Parke and Miss Dinsmore in active conversation, and was glad to bury myself in the pages of a novel with which I had been long burdened, but which had not before recommended itself to me.

The only time that I care to read a novel is when I am very busy, and ought not to. When I have nothing else to do, I lose all interest in it. In the present case, I was interested in watching the many changes that Miss Dinsmore's face was capable of taking to itself in a few moments. I had the impertinence to wonder where she was going, and why, and how it chanced that she was alone. Meanwhile, the conductor sat down beside me, and talked to me about Brainerd, which we were now rapidly approaching. I gathered from the conversation that the car-shops of the Northern Pacific were at Brainerd, and the machine-shops, and the boiler-shops, and a great many other places of the same sort, and that the railroad has a sanitarium there, where my conductor was taken care of, in a way that he praised at great length, on the occasion of a long illness. I had just entered in my note-book the fact that Brainerd had a population of 10,000, and that she had a most satisfactory court-house and jail, erected at a cost of $30,000, when we reached the station, and Miss Dinsmore and my corduroy friend plunged out into the night and upon the platform.

I considered that I already had cause for feeling aggrieved, but when my statistical young lumberman entered at this moment, I made up my mind that the good luck which I had always firmly considered my own had deserted me. No sooner did this painfully accurate young man perceive me, than he advanced with outstretched hand.

"How are you, Mr. Miller?" I said, stiffly. The reply was of a different sort.

"So glad to know, Mr. Key," he exclaimed, "that you are taking a continued interest in the resources of the country. Have been visiting a section that I know you would have been interested in. There is a magnificent pine forest lying up here to the north. There is enough pine in it, sir, to build fifty cities with, and a navy of ships. I am putting it mildly, sir, upon my word I am. If you want to see a sample of that lumber, you ought to visit Gregory Park, right here in Brainerd, where there are ten acres of pines set aside by the town." Mr. Miller always spoke of trees as "lumber," as you might expect a butcher to refer to cattle as "beef."

Parke came in with Miss Dinsmore, and heard us talking. The two sat down by us, as if they had not been rude to me, and of course I introduced Miller. Parke looked Miller over slowly, and put the expected inquiry.

"Pardon me, sir," he said, "but are you a sportsman?"

I smiled softly to myself, and offered Miss Dinsmore my novel. She accepted the stupid thing with a look of gratitude, and I forgave her for the way she had treated me. After that I did not care how many statistics I had to listen to.

My corduroy friend was enthusiastic over what he called the "Lake Park Region."

"Have you never heard of that remarkable chain of lakes?" he exclaimed to me, when he saw a look of ignorance in my eyes. "Mille Lac is only twenty-two miles southeast of here, and that is—"

But Miss Dinsmore interrupted him.

"I dare say you do not know how beautiful a butternut grove is," she said to me. "The trees are so generous, so beneficent, that you feel safe and comfortable as you walk under them. And of all things that I know of in the way of forests, there is nothing I more admire than one of maple. These two trees, the butternut and the maple, grow side by side, and a long beach of white gravel runs down into the green water. There are ferns and mosses and the gentian in the woods, and in the right season one can pick hundreds of strawberries there. There are cranberry marshes near, and blueberries and raspberries grow wild. One can fish there and shoot, but I do not think," and she cast a reproachful look at the corduroy man, "that any appreciative person would want to destroy anything in such a beautiful spot." Parke shook his head at this, to him, inexplicable remark, but he knew better than to openly oppose a young woman with a chin like Miss Dinsmore's.

"I've just come down from Duluth," the lumberman remarked to Miss Dinsmore, "and I assure you I have seen some beauties."

Miss Dinsmore looked shocked.

"I hope you are not referring to ladies," she said.

"Madam," returned the lumberman with dignity, "I am referring to lakes. They are scattered among the most placid and delightful meadows, and at this season these meadows are covered with gold and purple flowers."

"The golden-rod and the aster," said the lady.

"I suppose you may not be acquainted with the fact," Miller said, "that Minnesota has no less than 10,000 lakes."

"You don't say so!" excitedly cried the corduroy man.

"You are thinking what an opportunity there is for killing," cried Miss Dinsmore.

"I suppose I am to be looked upon as a sort of public executioner," protested Parke.

We had got on the subject of lakes, and we could not get away from it. Every town we stopped at was said to be in the vicinity of some lake, and I learned that in the season this part of the country was the particular resort of the sportsmen, who, though they came by the thousand, were literally swallowed up in the vastness of this solitude, and often traveled for days without meeting a companion.

Before we reached Wadena, Miss Dinsmore had retired, after playing a merry little tune for us on a zither, the case of which had attracted my attention. We three men went out on the platform. A rolling plain lay stretched out beyond us, broken with gentle groves. The little place seemed to have an abundance of activities. Two grain elevators loomed up black in the starlight. I heard from a drummer that there were six hotels in the place, a flouring-mill, with a

capacity for 100 barrels a day, a foundry, and a large trade with the surrounding grain country.

capacity for 100 barrels a day, a foundry, and a large trade with the surrounding grain country.

The drummer had just come from the Black Hills Branch of the Northern Pacific. This runs west from Wadena. He, too, was talking about lakes, and aroused the enthusiasm of the corduroy man to such an extent that he had an extra "lay-over" marked on his ticket, and left us to test the delights of Battle Lake—or rather the two Battle Lakes, famous for their beauty of dell and cove and shore, but more famous still for their marvelous variety of fish. We traveled a few miles together before the proper station was reached, Parke meanwhile gathering up his endless quantity of traps, and turning one enraptured ear to the recital of the tales of wonderful catches that the commercial gentleman poured into it. I, unfortunately, made no note of these tales, and can not reproduce them. To a man who knows nothing about fishing, and who has never read Izaak Walton since his early youth, these stories naturally have little point. I was more interested in the description of a chain of lakes much sought by the canoeist, and having easy portage between them. I peered out of the window into the darkness, wondering how far distant was that melancholy ground on which the Indians of the Sioux and Chippewa Nations poured out their fierce and hereditary hatred in such unavailing strife.

The instructive drummer spoke of Fergus Falls and Wahpeton, on the Fergus & Black Hills Branch, as being good towns to do business in, both now rejoicing in elevators, the inevitable court-house, opera-house, and factories and mills.

Detroit was the next point passed which offered particular attractions to me. This is becoming a very popular summer resort, having a hotel of gay architecture, suggesting midsummer pleasures, situated on Detroit Lake, a crescent-shaped sheet of water, with alternate banks and beaches. The lake has attractions of the sort likely to allure my corduroy friend, but it is sought especially as a place of refuge from the heat of the East in the months of July and August. The town itself is in a bower of trees, and forests flank it.

At Winnipeg Junction I bade good-bye to my friends with a certain regret—not because I was fond of them. I did not consider it good form to be fond of anyone on such short acquaintance. Impulsiveness is a characteristic of the Wild West. In the East we temper our enthusiasm with discretion.

I arrived in Winnipeg the next clay, having enjoyed all the conveniences of a Pullman sleeper and dining-car by the way. Winnipeg is a town which quaintly combines the enterprise of the present with the relics of an interesting past. The Hudson Bay Company (vaguely associated in my mind with dashing French voyageurs, with the Indian at the best of his alertness, subtlety, and daring, and with fur-hung halls where the nights of rare reunions were spent in memorable carousals) has here a most important post, and it still represents a wealth and power which has only ceased to seem extraordinary because the mind has become accustomed to the idea of great commercial organizations.

Winnipeg has a population of 25,000, at which I might have been surprised had I not learned the extent of her trade relations, which extend through the Canadian possessions as far west as the Rocky Mountains.

Three days later, having transacted my business, I took the train for the South, first by the Northern Pacific & Manitoba road, and then by the Duluth & Manitoba Division of the Northern Pacific.

It was one of those clear, bright days, with a brisk wind, so common in that climate, and the world looked especially clean and well cared for, as I went rushing southward. Pembina is the oldest town in the whole West, having been settled in 1801, by the colonists brought to this country by the Earl of Selkirk. The population is peculiar. Canadians, French-Canadians, Icelanders, and Americans make up the little town, which, in ceasing to be a mere trading-post, has become the market for the rich farming country round about. The valley of the Red River of the North has a fame for hard spring wheat which had reached even my ears—who am the most ignorant of men on such subjects. And I now learned that the yield was seldom below twenty bushels an acre, and often over thirty. Grafton is another town whose prosperity is owing to the rich agricultural country in its vicinity, and Grand Forks, which has a population of 10,000, shares the same advantage, and adds to it an active industry in logging. Red Lake Falls stands at the junction of Clearwater and Red Lake rivers, which, between them, have no less than thirteen water-powers.

I found myself not averse to getting back to Winnipeg Junction, for I had a hope that I might meet some of my old acquaintances. I was beginning to lose my dread of the statistical lumberman, and to forgive the corduroy man for suspecting me of an inclination to kill, and I never did lay up her sex against Miss Dinsmore. That young lady was to stop off with friends for a few days, somewhere, and the lumberman being on a tour for the express accumulation of knowledge, and the sportsman being the creature of caprice, I was likely, if my luck did not desert me, to meet any or all of them at any time.

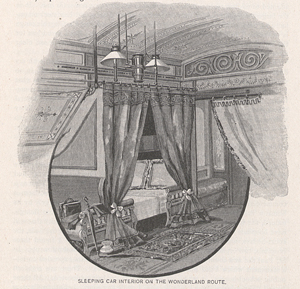

Business done, I was ready to devote myself to pleasure—or the nearest approach to it that I could hope to find. So I settled down to a quiet enjoyment of the days, caring little what turned up next. I had a consciousness that I would sleep in a well-made bed, have well-cooked meals, carefully served, and the privilege of lolling all day in softly upholstered seats, and looking out upon an ever-changing scene. The prospect was comfortable. I was lazy—out of love with the world, and in love, just at present, with idleness. I did not imagine that the West held any personal interest for me, but I did not object to looking at it—it is as well to encourage these young and struggling communities. So, with a silk dust-cap on my head, my feet comfortably encased in patent-leather ties, a pile of novels by my side, a box of cigars always in easy reach in the dining-car, I settled down to my journey, and wondered how long it took a New York woman to forget a man she had driven to despair; but the most humiliating part of it was, that in spite of all attempts to summon up sentiment on the subject, I was disgustingly comfortable in spite of the despair. Whether it was the cooking, or the scenery, or the natural revolt of the mind too long troubled, I do not know; but the fact remains, I was comfortable.

Figures do not mean very much to me, and the facts that I heard adduced by the many statisticians that I seemed fated to meet did not make the impression they were expected to. As I left Minnesota, and entered upon the prairie stretches of Dakota, I was entertained by the sight, entirely new to me. Here were the plains, but a few years ago the haunt of the Indian and buffalo! Now, the wheat of North Dakota has the reputation of being the best in the world, and when one remembers how recently it acquired this reputation, and compares the population of the State at present with that of five years ago, he is persuaded that no country contains more surprises than these United States.

In this section of the country, a yield of twenty bushels per acre is usual, and twenty-five bushels is not surprising. The flour produced from hard spring wheat is said to be an especially valuable commodity, bakers being able to get 250 pounds of bread from a barrel of flour made from the spring wheat, and only 225 pounds from the same quantity of flour ground from winter wheat. At Fargo I made a note, in my fast-filling memoranda-book, to the effect that the Northern Pacific sends out a branch road, called the Fargo & South-Western Branch of the Northern Pacific Railroad, which extends to Lisbon and La Moure, both thriving towns in the midst of a good agricultural country. At Edgeley, the western terminus of this line, it is possible to make connections with the Milwaukee road, and at Oakes, the terminus of a southern extension, with the Chicago & North-Western.

Having communicated these facts to my invaluable book, I was delighted to see, approaching down the length of the car, Miss Dinsmore, accompanied by two elderly and discreet ladies. With a friendliness I thought very flattering, Miss Dinsmore took a seat adjoining mine, and introduced the two discreet ladies as her aunts. Then she helped them remove their brown veils, which were exactly alike, as were all their clothes. The ladies were not well seated before I met with another surprise in the appearance on the scene of the familiar figures of the lumberman and the gentleman in corduroy. I was naturally surprised at seeing all of my old friends appear together, but I thought it would be rude to ask questions, and contented myself with beginning a conversation such as I hoped would meet with the approval of the elderly ladies.

"A beautiful country," said I, affably.

"'Tis, for them that appreciates it," said one of the ladies, who was evidently more decisive than grammatical.

"I'm sure I appreciate it," I said in an injured tone.

"Well," said the decisive aunt, "you look as if you had sense."

Miss Dinsmore smiled at me. I have always heard that women who have not fine teeth laugh with their eyes; but the young lady opposite had certainly no occasion for concealing her teeth. I was afraid, in spite of Miss Dinsmore's

presence, that the society was going to be depressing, when suddenly one of the aunts, who apparently had a desire to be hospitable, opened a small basket, and offered a portion of its contents to me.

presence, that the society was going to be depressing, when suddenly one of the aunts, who apparently had a desire to be hospitable, opened a small basket, and offered a portion of its contents to me.

"Better take a doughnut," said she, sociably. "You are likely to get hungry fifty times a day on the cars." I refused with some embarrassment, and Miss Dinsmore came to the rescue.

"There is no need for fretting about hunger in this land," she said. "Fargo, you know, is the headquarters of the Northern Pacific Elevator Company, and I hear they have fifty elevators round about here. I have been out visiting the Dalrymple farm. I suppose you do not know what that signifies, Mr. Key. There are twenty square miles of wheat there—I never felt so proud of my country as when I saw that wheat-field. You can not imagine how yellow that wheat was, or how responsive to the wind. When the sun and shadow played over it there was not one shade of yellow, but a hundred. It is the very embodiment of plenty! And in harvest–time twenty–four self–binding reapers are driven over the fields at a time, cutting, so I have heard, at one sweep a swath of 192 feet."

My two friends, the lumberman and the sportsman, did not seem interested in this conversation. In fact, they appeared to unite in taking a very serious view of life. I discovered Parke darting vicious side-long glances at the discreet and elderly aunts. The ladies moved to the other side of the car to enjoy something of peculiar interest in the landscape, and I went over to where these dejected fellow-travelers were sitting.

"What are you doing in this country?" I asked. "There are no trees to measure and nothing to kill, unless it is prairie dogs."

They both looked at me and said not a word. I purchased a cigar and discreetly withdrew. Meanwhile the train went whizzing on through the beautiful Valley City in its amphitheatre of hills; through Sanborn, where a branch of the road runs north through a rich wheat country to Cooperstown, and on to Jamestown.

Substantial and pleasant is Jamestown with its compact brick blocks, its wide streets, and its enterprise. The gentleman in corduroy recovered his spirits sufficiently to tell me that the Jamestown & Northern Railway ran from here up to Devil's Lake, in which he assured me it was possible to catch fish of the most remarkable size and quality.

"And if you want to shoot geese, you can't go to a better place for it," he added; but he said it sadly, and it was evident that a blight had fallen upon his once exuberant spirits.

We were pulling into the Coteaux de Missouri, that remarkable table-land which, like most glacial deposits, offers rich opportunities to the agriculturist. It lies between the valleys of the James and Missouri rivers, and runs north into the British possessions.

As we passed Steele, Miss Dinsmore came over to say that the introduction of trees not indigenous to the soil was succeeding very well in North Dakota, and that box-elder, cotton-wood, and willow were being raised in a large nursery in the vicinity. It was strange for a woman to be so exact in her information, and I remarked as much to her. She said she had an interest in the country at large, and had read up on Dakota. But I saw there was something behind this, for the two gentlemen looked darker than ever. But, nothing daunted, Miss Dinsmore discoursed to me on the wonderful richness of the sage-brush land. To a man raised in the East, a stretch of sage-brush has a most discouraging appearance. It seems like a curse and a blight. But I soon became convinced that when once the sage-brush is removed, it is the richest farming country in the world.

"Dakota does not seem to have many rivers," I said to Miss Dinsmore, to test her information on the subject. She was up in arms in a minute—quite as if I had been depreciating a piece of personal property.

"I am surprised to hear you," she cried. "Beside the Missouri and the Red River, which are navigable, there are the Cannon Ball, and the Heart, the Sweet Briar, and the Little Missouri. And, speaking of water, the Dakotas have the most remarkable system of artesian wells known in the world. The range of present wells east and west is fully fifty miles, while north and south it follows from Yankton, on the Missouri River, to Jamestown, here on the Northern Pacific Railroad. The James River Valley is the center of the water belt. There are also two other areas of subterranean water partially exploited, and they are both in North Dakota. In addition to the rivers and the wells, the Dakotas have a large area covered with small lakes and lagoons. So you see, Mr. Key, there will be no lack of water here."

"Good thing," said I, "seeing what the prohibition tendencies are."

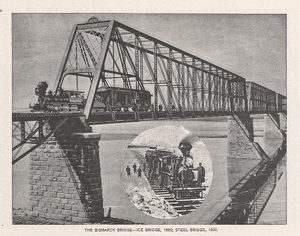

We passed through Bismarck, the capital of North Dakota, a healthy town with a reputation which needs no confirmation from me. Miss Dinsmore whispered that there was coal in the region of which there were good reports. She warned me that I should miss much if I stayed in the car, for we were about to cross the Missouri on one of the finest bridges in the western country. Therefore, against all rules, we stood on the platform and craned our necks over to view with admiration this wonderful structure of trusses, piers, girders, and cords of steel and iron. The Missouri, yellow and strong, flowed southward.

"It is a little pathetic," said Miss Dinsmore, who was leaning over the brass bar in the vestibule of the car, "to look up this Missouri Valley and think of the change that has come to it. The Indian has gone, and the buffalo; and the bear and the beaver are all but gone. We turned the corn-fields of the Indian into battle-grounds. Civilization must go on, I suppose, but it is rather hard that the Indian must always be the victim of it."

We arrived at the village of Mandan, and, getting off at the station, wandered into an excellent curio shop that invites the promenader from the platform. The owl and the eagle, the American lion and the grizzly, are all here. There were some specimens of exquisitely decorated pottery here, also, which had been dug from bluffs two miles from Mandan, at the junction of the Hart and Missouri rivers. Here are the remains of a mysterious people for whom the students have not yet been able to account. They show a knowledge of art which certainly was not possessed by the American Indians as we have know them. The cemetery of this gigantic race covers about 100 acres, and will furnish interesting study for some American Schlieman.

I must not forget to mention that Fort Abraham Lincoln lies five miles southwest of Mandan.

Just beyond Gladstone lies Dickinson, which, with its brick manufacturing, its sandstone and coal-beds, lies in the midst of a country well adapted to agriculture and grazing.

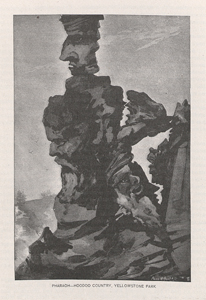

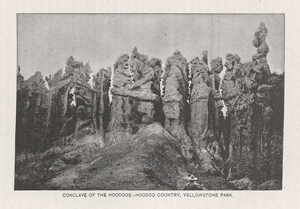

It chanced to be nearing twilight as we came into the Bad Lands; these are more popularly called Pyramid Park, but I cling, myself, to the name given them by the old French voyageurs.

A gentleman of universal information pointed out varieties of lignite, argillaceous limestone, friable sandstone, and potsherd, and gave me a dissertation on the Pliocene Age, and the effects of fire and water; but I saw the place with different eyes. To me it was a blasted heath, on which Macbeth's witches might have met; or a spot that might appropriately be selected by the witches in which to celebrate Walpurgis night. Buttes of brown, of gray and white with tops of red and cuts of dull, sulphurous blue, twisted and rent, and distorted into shapes so tortuous that to my mind they suggested only suffering and strife, stretched out before the eye everywhere. My friends told me that the land was not unwholesome—that even on the top of these stricken-looking hills, rich grains and vegetables would grow; but the dance of the witches was all I could see, and I was sure I should never seek to dwell among such scenes, unless, in some hour of deeper depression than I had ever experienced, I should find a subtle sympathy amid these grotesque and unique scenes.

At this time I noticed that a strange quiet was falling upon our party. The discreet maiden aunts no longer helped themselves to wafers from their wicker baskets. Though Miss Dinsmore's cheeks were red, and her eyes were unusually bright, she had ceased to converse; and as for the two gentlemen, their gloom had deepened until, as Charles Lamb has put it, "they might have thrown a damper over a funeral."

We had just reached a little town which intruded its calm commonplaceness into this astounding scene, when Miss Dinsmore volunteered the information that she should leave us at the next station. I expressed my dismay with a gesture.

"Yes," said Miss Dinsmore; "I am going to live back here in the country about fifty miles." I regarded her in horrified astonishment. She colored, but it was evidently not from resentment.

"You see," explained Miss Dinsmore, "I stopped at Fargo to get my aunts,

who have come on to attend my wedding." That explained everything—the depression of the lumberman and the corduroy man, and the subdued mood that had fallen on the party.

who have come on to attend my wedding." That explained everything—the depression of the lumberman and the corduroy man, and the subdued mood that had fallen on the party.

"I am delighted to hear it," I cried. "I presume that you know where you will find anyone in this country to marry, but I can see nothing but blasted rocks and barren valley."

"Then I will tell you what you shall do," Miss Dinsmore cried; "you shall come to my wedding, and I will show you miles of fertile valley behind these rocks where your witches dance, and instead of its being a spot selected by Mephistopheles from which to curse the world, you will find plenty and comfort, and, what will doubtless surprise you more, companies of good jolly fellows who make the best of friends."

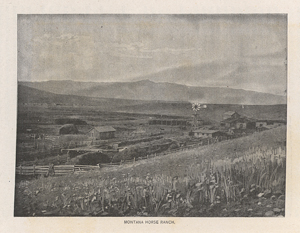

Then she dilated upon the great cattle ranches, and the home-like "shacks" where the ranchmen live. After this, it was not hard to guess that it was with one of these ranchmen, and in one of these "shacks," that Miss Dinsmore expected to find consolation for living in such a country.

We left the road at Mingusville, and I was pleased to find that the lumber-man and the gentleman in corduroy were to accompany us; but it being already the "edge of evening," as Lowell puts it, and the road being tortuous in the extreme, it was thought best for us all to wait over night at an inn. The gentle man to whom Miss Dinsmore had paid the compliment of coming across the Dakota plains to meet, joined us. He was an enormous young fellow, with a black, drooping mustache, slightly faded by the sun, who, in spite of the fact that he had come to meet his bride, wore a gray flannel shirt, knotted at the throat with a silk handkerchief of the most uncompromising tints. He was so full of life and activity that I was in constant fear that he might break some of the furniture, or tread upon my toes—an offense which I never forgive—or accidentally sit upon one of the prim maiden aunts and demolish her. I have never yet met a young man of whom there seemed to be so much. It was not his size alone; it was what in Boston they would call his "atmosphere."

The next morning, mounted on a number of the capricious cayuses, we started on our journey. The sun was still low in the east, red and large, and phantasmal mists were wreathing about all these uncanny hills and hollows. I felt as if I were riding through the land where the German gnomes dwelt, and would not have been surprised at any moment to see a troop of them, hump backed and hideous, working with their anvils in this infernal forge, where the scoria of dead fires strewed the ground, and in some hollows of which mines of lignite were burning, as they had been ever since the memory of man—a sort of eternal adoration to the unwholesome spirit of the place. A few gnarled, twisted trees, which seemed to be protesting against their lives, grew by the water-courses, and all over the country grew the short bunch-grass, which, when it is cured, is said to make nutritious hay; and side by side with it grew the sage-brush, the color of the mistletoe. Brown, bare, and bizarre, the landscape stood for the very incarnation of desolation and grotesquerie. The cattle roam in great herds over "round-ups " of fifty miles or more, feeding on the fine prairies back of the buttes, in the summer, and in the winter taking refuge among the buttes and in the sparsely timbered sections.

It was two days before I left the hospitable shack of my friend, the ranch-man. I need not tell all I saw in this remarkable country, but I was convinced that it was possible for a man to make a fortune there if he understood cattle-raising. A wild, adventurous, not unfascinating life it is, with a rich promise of opulence to aid the patience and assist the judgment. As for the interior of the shack, it was one of the most delightful I ever saw. The floors were covered with beautiful skins, the walls decorated with antlers, and cabinets of the exquisite crystals and agates chipped from the buttes of Pyramid Park; the great fire-place was made of squares of the red potsherd, cemented together; three or four hammocks hung about the room; a buffet, not innocent of select cordials and liquors, some fowling-pieces, and a guitar, made up an ensemble which could not but be inviting. I was relieved, too, to find that my little friend would not be without woman's society here. Many of the ranchmen have their wives with them, and it goes without saying that where is money there will be gaiety.

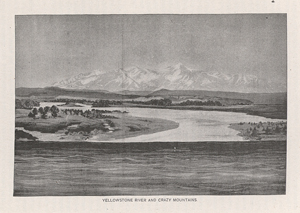

Bidding farewell to our friends, including the discreet maiden aunts, I and my two traveling companions returned by the same weird road over which we had previously journeyed, and took a train bound for the setting sun. For 340 miles we followed the windings of the Yellowstone, a river so clear and bright, so full of bewitching cascades and green islands, that it seemed each hour as if it had been freshly born and had no relation with this old and weary world.

We passed the lively town of Glendive, and then several quiet and wholesome hamlets, at last reaching Miles City, a town which has the distinction of being the only one, save Bozeman, on the Northern Pacific lines which did not owe its origin to the building of the road. It is at present the key to a rich cattle country, there being 700,000 cattle on the ranges round about. Ninety miles farther on, after passing through a historic tract of country, made famous with the names of some of our best Indian fighters, we came to Custer, the station for Fort Custer, which lies thirty miles distant, and, while not equaling Fort Keough, which lies just beyond Miles City, in its equipment or garrison, is one of the most notable military posts in the West. It was near here that the yellow-haired hero whose name the fort bears met with his memorable and tragic death.

Billings is a town of steady growth, situated at the foot of Clark's Fork Bottom, in the midst of characteristic Western scenery, at once picturesque and peculiar. It is only second to Miles City as a shipping-point for cattle; and gold, silver, and coal are found in the country tributary. The coal comes from Red Lodge, and the gold and silver mines are adjacent to Cooke City, and are reached by the Yellowstone Branch of the Northern Pacific Railroad in connection with a wagon-road from Cinnabar. The gentleman in corduroy deserted us at this point, being won by tales of wild hunting adventures in this country, and by the promise of marvelous scenery. "I will see you again," he said, as we parted. "I am sure it is our fate to meet. I would go on with you, but there is a canon south of here that men should be willing to travel a thousand miles to see, and I am too patriotic to turn my back on it."

At Big Timber, my lumberman deserted me, and I was obliged to go on my journey alone. He also paid me the compliment of saying that he parted from me with regret; and, while he could urge no canon in excuse of this disloyalty, he thought the flourishing saw-mill a sufficient excuse for leaving any man, even his best friend. I used to tell him that if he ever got to Heaven, and found the gates were really of jasper, he would refuse to go in. That man had no sympathy with anything but hardwood.

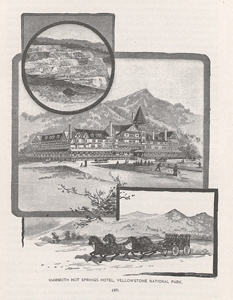

At Springdale we took on a number of persons who had been recuperating at Hunter's Hot Springs, and at Livingston—of which I will say more at another time—we left the comfortable seclusion of our Pullman car for a train less exclusive though equally luxurious, running south to Cinnabar, the gateway of the Yellowstone National Park.

I hardly know how to describe the ride from Livingston to Cinnabar. The road lies through the third or lower canon of the Yellowstone, which is an ancient lake-bed, and bears the name of Paradise Valley. Through it the river tumbles and pounds and laughs, clear as crystal and cold as ice. The rich ranches, stretching beyond the level up onto the moraines, look like great Persian rugs with their harmonious blending of colors. On each side the mountains rise, each bearing its grim history of volcanic struggles, of glacial epochs. On Cinnabar Mountain the strata is vertical, and in one remarkable spot, where the stratum of soft material is washed out, there is a formidable slide 2,000 feet in length between jagged walls of rock. But this is not a district in which one wishes to specify and particularize. I, and I am sure many others, will prefer to take it as a beautiful whole. At Cinnabar, coaches were in waiting to take us to the Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel, and we drove down through a rugged and majestic country to this capacious hostelry. There the evening was made memorable to me by three things—some excellent music, which I believe is provided every night of the summer for guests, the making of some pleasant new acquaintances, and the reading of that portion of Talmage's sermon, written after his visit to the West, in which he refers to the scenery of the Yellowstone Park. It was read to us by a young lady from New Orleans, with the dulcet inflections for which the ladies of her city are noted:

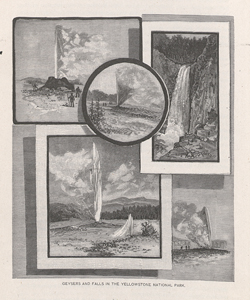

But the most wonderful part of this American Continent is the Yellowstone Park. My visit there made upon me an impression that will last forever. After all poetry has exhausted itself, and all the Morans and Bierstadts and the other enchanting artists have completed their canvas, there will be other revelations to make, and other stories of its beauty and wrath, splendor and agony, to be recited. The Yellowstone Park is a geologist's paradise. In

some portions of it there seems to be the anarchy of the elements fire and water, and the vapor born of that marriage terrific. Geyser cones or hills of crystal that have been over 5,000 years growing. In places, the earth throbbing, sobbing, groaning, quaking with aqueous paroxysm.

some portions of it there seems to be the anarchy of the elements fire and water, and the vapor born of that marriage terrific. Geyser cones or hills of crystal that have been over 5,000 years growing. In places, the earth throbbing, sobbing, groaning, quaking with aqueous paroxysm.

"At the expiration of every sixty-five minutes, one of the geysers tosses its boiling water 185 feet in the air, and then descends into swinging rainbows. Caverns of pictured walls large enough for the sepulcher of the human race. Formations of stone in shape and color of calla lily, of heliotrope, of rose, of cowslip, of sunflower, and of gladiola. Sulphur and arsenic, and oxide of iron, with their delicate pencils, turning the hills into a Luxemburg or a Vatican picture gallery. The so-called Thanatopsis Geyser, exquisite as the Bryant poem it was named after, and the so-called Evangeline Geyser, lovely as the Longfellow heroine it commemorates. The so-called Pulpit Terrace, from its white elevation, preaching mightier sermons of God than human lips ever uttered. The so-called Bethesda Geyser, by the warmth of which invalids have already been cured, the Angel of Health continually stirring the waters. Enraged craters, with heat at 500 degrees only a little below the surface.

"Wide reaches of stone of intermingled colors—blue as the sky, green as the foliage, crimson as the dahlia, white as the snow, spotted as the leopard, tawny as the lion, grizzly as the bear—in circles, in angles, in stars, in coronets, in stalactites, in stalagmites. Here and there are petrified growths, or the dead trees and vegetation of other ages kept through a process of natural embalmment. In some places, waters as innocent and smiling as a child making a first attempt to walk from its mother's lap, and not far off as foaming and frenzied and ungovernable as a maniac in murderous struggle with his keepers.

"But after you have wandered along the geyserite enchantment for days, and begin to feel that there can be nothing more of interest to see, you suddenly come upon the peroration of all majesty and grandeur—the Grand Cañon. It is here that, it seems to me—and I speak it with reverence—Jehovah seems to have surpassed himself. It seems a great gulch let down into the eternities. Here, hung up and let down, and spread abroad, are all the colors of land and sea and sky; upholstering of the Lord God Almighty; best work of the Architect of worlds; sculpturing by the Infinite; masonry by an Omnipotent trowel. Yellow! You never saw yellow unless you saw it there. Red! You never saw red unless you saw it there. Violet! You never saw violet unless you saw it there. Triumphant banners of color. In a cathedral of basalt, Sunrise and Sunset married by the setting of rainbow ring.

"Gothic arches, Corinthian capitals, and Egyptian basilicas built before human architecture was born; huge fortifications of granite constructed before war forged its first cannon; Gibraltars and Sebastopols that never can be taken; Alhambras, where kings of strength and queens of beauty reigned long before the first earthly crown was empearled; thrones on which no one but the King of heaven and earth ever sat; fount of waters at which the lesser hills are baptized, while the giant cliffs stand round as sponsors. For thousands of years before that scene was unveiled to human sight, the elements were busy, and the geysers were hewing away with their hot chisels, and glaciers were pounding with their cold hammers, and hurricanes were cleaving with their lightning strokes, and hailstones giving the finishing touches, and after all these forces of Nature had done their best, in our century the curtain dropped, and the world had a new and divinely inspired revelation, the Old Testament written on papyrus, the New Testament written on parchment, and now this last testament written on the rocks.

"Hanging over one of the cliffs, I looked off until I could not get my breath, then, retreating to a less exposed place, I looked down again. Down there is a pillar of rock that in certain conditions of the atmosphere looks like a pillar of blood. Yonder are fifty feet of emerald on a base of 500 feet of opal; walls of chalk resting on pedestals of beryl; turrets of light tumbling on floors of darkness; the brown brightening into golden; snow of crystal melting into fire of carbuncle; flaming red cooling into russet; cold blue warming into saffron; dull gray kindling into solferino; morning twilight flushing midnight shadows; auroras crouching among rocks.

"Yonder is an eagle's nest on a shaft of basalt. Through an eye-glass we see among it the young eagles, but the stoutest arm of our group can not hurl a stone near enough to disturb the feathered domesticity. Yonder are heights that would be chilled with horror but for the warm robe of forest foliage with which they are enwrapped; altars of worship at which nations might kneel; domes of chalcedony on temples of porphyry. See all this carnage of color up and down the cliffs; it must have been the battle-field of the war of the elements. Here are all the colors of the wall of heaven, neither the sapphire nor the chrysolite, nor the topaz, nor the jacinth, nor the amethyst, nor the jasper, nor the twelve gates of twelve pearls wanting. If spirits, bound from earth to heaven, could pass up by way of this cañon, the dash of heavenly beauty would not be so overpowering. It would only be from glory to glory. Ascent through such earthly scenery, in which the crystal is so bright and the red so flaming, would be fit preparation for the 'sea of glass mingled with fire.'

"Standing there in the Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone Park on the morning of August 9th, for the most part we held our peace, but after a while it flashed upon me with such power I could not help but say to my comrades: 'What a hall this would be for the last judgment!' See that mighty cascade with the rainbows at the foot of it! If those waters congealed and transfixed with the agitations of that day, what a place they would make for the shining feet of a judge of quick and dead! And those rainbows look now like the crowns to be cast at his feet. At the bottom of this great cañon is a floor, on which the nations of the earth might stand, and all up and down these galleries of rock the nations of heaven might sit. And what reverberation of archangels' trumpets there would be through all these gorges, and from all these caverns, and over all these heights! Why should not the greatest of all the days the world shall ever see close amid the grandest scenery Omnipotence ever built?"

After this it seems superfluous for me to mention anything I saw or thought in this wonderful country; but it is pleasant to write the assurance that not only will the visitor of the future see all that has been described by this most graphic of preachers, but he will also be able to visit the Yellowstone Lake, where hotels are now completed, and the steel-hulled boat, capable of accommodating 150 persons, is ready for use.

I left the Park with a feeling of physical vigor, but of mental fatigue. I had seen and felt too much. The excitement and exaltation had been too great, and I was glad to get among more commonplace scenes.

Of the many friends I had met in the Park, only the gentleman who bore the descriptive name of Mr. Bolter was to accompany me on my westward journey. He confided to me the fact that having spent two fortunes in traveling, he was now preparing to make a third, and was consequently in search of investments which would bring him quick returns. In these investments I afterward became much interested, and indeed the interest began at Livingston. Mr. Bolter decided that, as Livingston was the central headquarters of an important railroad division and the junction point of tire Park branch with the main line, it was bound to grow, aside from the fact that it is, and ever must be, the chief town in an important mining country, embracing such well-known camps as Cooke City, Castle Mountain, and Neihart. The demand for houses and the astonishing prices cheerfully paid for rent induced my speculative friend to purchase ground and order the erection of several substantial dwellings. As these residences were bespoken, to use the words of Mr. Bolter, even before the contract for their erection was completed, he started westward in the best of moods, and insisted on treating me at each meal to an economical bottle of Zinfandel. It was during these times that we gravely discussed the golden State of Montana and its future. I learned that the rivers in the State were navigated by steamboats a distance of 1,500 miles. I learned of the rich valleys by the large rivers; of the great growth of trees in the northwestern part of the State; of the vast ranges of cattle and sheep; of the sweet and nutritious grasses, and, above all and over all, the fabulous tales of mineral wealth.

As I write I observe in my note-book a little pasted clipping cut from an interview with Col. R. J. Hinton, Engineer to the Senate Committee on Irrigation. It is as follows:

"On the east side of the continental ranges, the abundant waters that supply and make up the Missouri and Mississippi all take up their rise and flow through Montana. There is enough water in them to easily reclaim 40,000,000 acres of fertile land, now entirely idle. The stream beds flow from 250 to 500 feet below the surface of the great table-lands. There are large valley areas also, but these areas will never prove as good farming land as that of the plains above. Good engineering, however, will be required to so impound the waters of these streams as to enable them to be turned from their beds for the irrigation of the table-lands. In Montana at the present moment only about 650,000 acres are under cultivation by irrigation. Bozeman is the center of the largest irrigated grain section. Missoula, in the extreme northwest portion of the State, promises to be the best orchard and small grain region."

With the promise of such wealth as this, I said to myself, added to the natural wealth that already exists in these brown and rugged mountains, what may not the State of Montana become! At Bozeman, a beautiful little city of 4,500 people, I learned that I was at the very gateway of Gallatin Valley, so noted for its wheat, its oats, and its barley. The Gallatin Valley, I remembered, was considered by the Senatorial Committee on Irrigation as one of the most salient examples of the good that could be worked by irrigation.

Near Bozeman are also rich coal-fields. These lie in close proximity to the town, and are of pure bituminous coal, excellently adapted for coking purposes, and being therefore available for the smelters. Bozeman is fortunate in its educational advantages, having, in addition to its public schools, a Presbyterian academy.

Near Gallatin, where the Madison, Gallatin, and Jefferson rivers unite with such equal and mighty force that the first explorers could not tell which of them deserved to be called the continuation of the Missouri, I saw the new branch road of the Northern Pacific, running south and west to Butte, and bringing that city 120 miles nearer St. Paul. The next two weeks were spent by my speculative friend and myself in a country which can never fail to impress itself on my imagination.

These days are so full of interest that I hardly know which to speak of first. There was the day at Townsend, for instance. Townsend is in itself a quiet little place, more interesting to the tourist for the reason that it sends a daily stage to White Sulphur Springs than for any other reason; but not far from Townsend, across the Missouri Valley, in a northwesterly direction, is a wonderful series of precipitous cañons among the mountains. Cut and wrenched by the elements and fantastically colored, polished with avalanches and beautified with mists, Hellgate Cañon presents the most awful beauty that can be found in the State of Montana. To tell the truth, for the most part the mountains are not impressive around Helena and Butte; they are generous swelling hills, mighty in size, but not impressive to the eye, and when not covered with snow are clothed with the russet–colored grasses.

We reached Helena on a September day, and the picture that we saw was a brown one. Everywhere the generous hills rose up to the sky, covered with that uniform brown tint; the very buildings themselves seemed to tone in with the prevailing color; the sky made the only variation. Stretching out beyond the city lay the fertile Prickly Pear Valley, and up and down the slopes of the streets climbed the houses built on ground that has become more valuable than the gold that used to be washed from those same streets in the days of the rich placer mining.

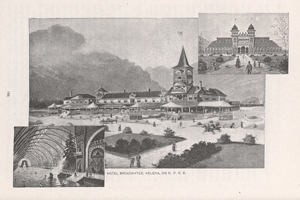

My friend and I registered at the Broadwater Hotel. The Broadwater, which is located on the Northern Pacific Railroad, near the city, is one of the most remarkable hotels at which it was ever my privilege to stop. It cost, so I was assured, and as I can easily believe, $350,000; but this includes a pleasant park, whose greenery is most grateful to the eye wearied of that brown landscape. And it also has a sanitarium at which the people of Helena find no little part of their amusement. A steam street motor runs from Helena to the Broadwater, which lies about three miles distant from the city, and passes through the imposing residence portion in which stand the homes of many millionaire miners.

The occasion for the building of the sanitarium in this green glen is the existence of the Hot Springs, which contain chemicals said to be especially desirable for a person suffering with the rheumatism. I did not suffer with the rheumatism, but I was quite willing to enter the sanitarium, whose Moorish architecture at once attracted and puzzled my eye. Once within, I stood astonished. A tank, 300 feet long and 180 feet wide, of clear, steaming water flowed before me. Above was a roof of arched and polished pine; around, a glimmer of prismatic colors, for the sides of the building are of glass of the most brilliant tints. At one end of the tank, over a great pile of straggling rocks, flows a small cataract of green water; and oriole windows, set with stained glass, are so arranged that, in whatever position the sun chances to be, a rainbow is sure to play in this musical, swift-flowing fall. But this was not all that interested me. All about this pile of rocks, right in the clear rush of water, stood groups of nymphs—nymphs, it is true, in very modern bathing–suits. Their attitudes were none the less graceful from the fact that they were not free from self–consciousness; and all the while the air was rent with the playful shrieks of several hundred more nymphs who disported in the tank below. With tumbled, dripping hair and flourish of white arms, and struggling and gurgling as some inexpert swimmer went beyond her distance in the tank, with fights in which Neptune and Aphrodite might have taken part, and the ever-changing transformation up there in the falls where the prettiest of the nymphs posed, an hour passed very rapidly.

The hotel itself is furnished in exquisite taste, with cool, inviting bath–rooms among its luxuries, and a table service as dainty and complete as anything one could find in the most luxurious home. Sitting here in the pleasant office I fell in with a gentleman who, in the phraseology of the country, had recently "struck it rich."

This man's history was a tragic one. His manners were convincing, being a reminiscence of the time when it was dangerous to question the accuracy of a Montana citizen. He was the most hospitable and friendly of men to his friends, but to his enemies—but I mistake. He had no enemies. They were all dead. Fortunately for my health, we were friends, and he used to smoke my cigars with child-like confidence.

"I've been a trail-blazer in my day," he vouchsafed, "an' there aint no man in this country knows more 'bout the place than me."

This honest pride was justified by the facts he confided to me and my note-book, some of which I reproduce, seeing in my mind's eye, as I do so, this good man with his hard hands, his keen eyes, his checked suit, diamonds, and high-heeled boots.

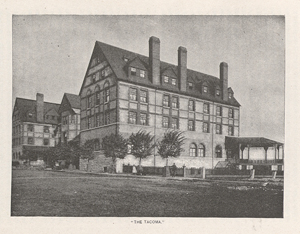

From him I learned that Helena, standing, as she does, midway between Tacoma and St. Paul, has a signal advantage commercially. She boasts a population of 22,000, an increase of 10,000 in three years. She is the capital of the proud young State, and is likely to remain so. Until 1892 this honor is assured her by her charter. In her First National Bank alone she has a deposit of $4,000,000. And this is a fair indication of the immense wealth invested in the mines, smelters, flumes, and cattle ranches round about. Her two reduction works each have a capacity of fifty tons daily. Millions of dollars have been expended in her great smelter. Business blocks and residences of pretension and a solidity, too, seldom met with in America, are being raised in every direction. This is the result of no unhealthy "boom," but conies from a sort of concerted action on the part of Helena citizens. For many years, now, fortunes have been a-making at Helena, and the people have a reckless way of referring to millions where the more discreet easterner would speak of thousands. But only recently has the rich man of Helena come to appreciate the significance of his money. In short, the people of Helena have passed the first stage of wealth, and reached the second. They have made their money; they are now beginning to spend it.