Political Allusions: The Pullman Strike

Although many elements of the Gothic Romance influenced Elia Peattie's characterization and plot in "The Fountain of Youth," the conventions of utopian/dystopian fiction serve as the dominant vehicle to transport her weighty agenda. "Utopian works make critical statements in fictional, or nonfictional, form about our social values, practices, and institutions." Dystopic fiction, on the other hand, "alerts us to the possible negative impact on society of certain practices, desires, and arrangements of power, and thus cautions us to proceed with care, altering our society's priorities." [1] The power of such stories lies in the characters' conflicts with such arrangements of authority. William Steinhoff explains, "Whether the story hinges on a search for love or spiritual health, a longing to recapture the past, a desire to make the best of perceived talents, or a bid for freedom, the struggle is set in a political context in such a way that the motives and the conduct are shown to be inseparable from political assumptions. Each of the major characters is an underdog, a lonely human being pitted against an oppressive, seeming invulnerable "society." [2] Thus, utopian and dystopian literature reflects the "specific preoccupations" of the times, and as such, "can be analyzed sociologically and politically." [3]

As in much of Peattie's writing, important subtexts lie beneath her often romanticized plots. When Peattie published the first installment of "The Fountain of Youth" Omaha World-Herald in October 1894, America was struggling to make the transition from a largely agrarian way of life to an increasingly urban, industrialized, and class driven society. Then, as it was attempting to pull itself up by its bootstraps after the depression of 1893, the Pullman Strike, which lasted from May to July 1894 and was the first national strike in American history, strained citizens' belief in the American Dream. Peattie was familiar with the details of the incident, for in her history, The Wonderful Story of America published in 1895, she records the events leading up to the strike and its aftermath. Her only editorializing in an otherwise objective history is to call it one of "a series of most disastrous labor disturbances" and to hint that President Cleveland's action in deploying federal troops was "characteristic of the chief executive," that is, one she did not support. [4]

Because of George Pullman's attempt and failure to create a model workers' community, Peattie's use of utopian conventions, the most popular type of literature between 1888 and 1900, works perfectly to present her views to the large audience that she wanted to reach. Most Americans believed that "serious literature should be didactic–an expression of the author's faith in the power of the written word to affect behavior." [5] In "The Fountain of Youth," Peattie does not present a blueprint for an ideal American society but rather asks her readers to think. In that, she is much like her heroine Opaka, who explains, "I only tried to get the young men and women into the way of learning all of the secrets of life for themselves. Believe me, my pupils think what they choose. I do not force my own beliefs down their throats. I only tell them to think."

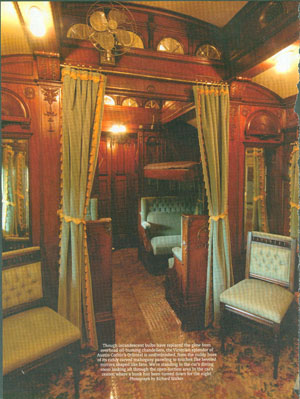

George Pullman, the originator and owner of the Pullman Passenger Car Company, made a fortune on his sleeper and luxury cars as railroads scrambled to span the United States after the Civil War. Scientifically minded like others of the Progressive Era, he put his management skills to work to solve labor problems he believed were caused by the low wages and poor living conditions endured by workers. He reasoned that if he built a "model town," workers would be healthier, contented, and more productive than if they lived in the tenement houses and slums of Chicago. He wanted to prove, explains Jonathan Bassett in "The Pullman Strike of 1894," "that the interests of labor and management were really one in the same, and the responsible capitalists would solve some of the pressing social problems created by capitalism itself." [6]

Pullman purchased 4,300 acres near Lake Calumet, twelve miles south of the central business district of Chicago, right beside his factory, and began his experiment in utopianism. He commissioned the building of 1,800 brick dwellings, including row houses, apartments, duplexes, and a few single family homes. [7] Modern in every way, they provided gas and indoor plumbing, considered a luxury in that age. The front yards, sodded, terraced, and beautified with plants and 30,000 trees furnished by the corporation-owned greenhouses, were kept mowed and watered by the company, who also daily removed all rubbish and ashes as well as maintained the homes in good repair. [8]

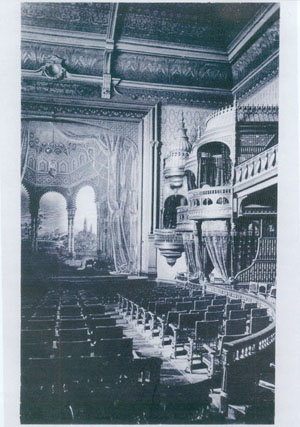

The public buildings planned by Pullman contributed to his model community and included a school offering free education through eighth grade, a livery stable, a market that sold meat and vegetables, the Casino, the Hotel Florence, and the two-story Arcade, which housed the library, theater, bank, commercial establishments, offices, and meeting rooms–all steam-heated. Pullman built one church, the Green Stone Church, and a parsonage and established a lumber yard, ice houses, and a dairy farm with one hundred cows to provide the residents with milk, cream, and butter. Gas lights illuminated the macadamized streets and plank sidewalks, and two parks, Lake Vista and Arcade Park, beautified the town. The parks featured winding roadways for Sunday drives, a lagoon with a waterfall, a bandstand, numerous flowerbeds, and a Playground and Athletic Island for sports. About 12,000 people lived in the town of Pullman, and during the Chicago World's Fair of 1893, more than 10,000 visitors toured this workers' utopia. [9]

Like the World's Fair visitors, when Shadwin and his friends first arrive at Bimini, they are awed by the beauty of the land. "Then suddenly, like a great curtain, uprolled the mist, until the folds of it, going skyward, became gold, and beneath this draping of beauty lay a land where the flowering vines clothed the trees, and from the breeze that had scattered the mist blew us odors of spice, and champak and lotus bloom." They are taken to De Vega's home, "a quaint arrangement of bark," whose windows, curtained with cloth embroidered in gold thread, opened onto a garden where a fountain splashed and "an orange tree poured out its fragrance into the night."

When the men recover from the hardships of the journey, they begin their tour of the town where lovers walk arm in arm down the scented, palm-lined avenues, and the people are "as happy as birds, born to build nests and sip the dew from the hearts of roses." They visit the church, airy and unadorned, where all of the people follow the Christian faith and worship every morning surrounded by a cross of gold. [10] De Vega also takes them to his gold mine, the only one on the island, and his cedar sluice that carries water to the village. A wealthy man, De Vega oversees one hundred miners and smelters. The workers' dwellings, which cluster near the mouth of the mine shaft, amaze Shadwin. Compared to the miners' hovels in America, these are "shapely little sheds, surrounded by exquisite scenes, and having within an air of pride if not elegance." The workers' wives are "comely and coy" and spin native cloth at their looms. De Vega prides himself in being a master that considers only his workers' well-being. As in Pullman, the workers live next door to their workplace, their homes are neat and comfortable, their surroundings beautiful, and their patriarch proud of his accomplishments. In Bimini the people live in everlasting youth, and there is "nothing left to long for."

George Pullman believed that he had satisfied every desire of his workers in his model city. A calculating capitalist, however, he had entered the venture expecting to gain a six percent dividend on his investment as well as preserve a stable labor force. [11] To him, workers were simply a commodity to be controlled, and his rule over the town and his laborers was rigidly paternalistic. As a result, the realities of life in Pullman were far from ideal. Theoretically, workers could live anywhere, but in actuality, they would not keep their jobs if they did not live in Pullman. Since he owned the entire town, his domination reached from the maintenance of all utilities to the election, through threats and intimidation, of all town officials, including the school board. When signing the leases to their homes, workers had to agree to rules covering everything from the care of their lamps and stoves to curfews, dress codes, and individual cleanliness and conduct, especially drunkenness. This paternalistic authority gave them little freedom. [12]

Since Pullman considered his community as a money-making venture, the entire cost of the town was borne by the inhabitants, and he made great profits selling the workers their gas and water. Although rent for workers was higher than in surrounding areas, the quality was superior, for every home had indoor plumbing. [13] In addition, the eight thousand volume library could only be accessed by "members" willing to pay the three dollar fee. In addition, Pullman wanted all of the denominations to merge, so he only constructed one church and parsonage, but the rents were so high, no congregation could afford either. [14] At first, the company deducted workers' rents and assorted fees from their paychecks, such as street cleaning and home repair, but when the government outlawed this, they simply gave them two checks, one which covered their expenses, which they had to sign over to the Pullman bank, and the other, if any was left, they could keep for themselves. [15] "Paternalism, instead of promoting better relations between employees and employer, had actually provided the laborer with new grievances and placed in the path of industrial peace an insuperable barrier," argues Almont Lindsey in "Paternalism and the Pullman Strike. "Improved living conditions and a favorable environment contributed only in part to the contentment of labor. Freedom of action and the right of self-expression were equally important." [16]

Peattie alludes to the paternalistic tyranny of Pullman in "The Fountain of Youth" through the character of Governor Diaz. As Shadwin and his friends become more familiar with Bimini, they begin to feel uneasy. They learn that although people remain healthy and do not age, they can be put to death for a myriad of offenses by Governor Diaz, who dresses in a purple toga like a Roman emperor and whose face manifests arrogance and cruelty. The state house where he rules has many pillars, like the Roman coliseum. In the Great Hall, two pictures dominate the governor's throne-like dais: one portrays the Fountain of Youth and the other depicts a mammoth plant encircled by vultures. Diaz's men compose the entire council, whose main purpose is to give the accused an "honorable trial" by voting with red or black disks as whether a person should be put to death. However, as in Pullman, the cards are stacked. Inevitably, the men vote unanimously per the governor's wishes. Moreover, Diaz, too, allows only one religion with no separation of church and state. Padre Anton, obsessed with power and vengeance, sides with the governor in everything, especially in the shared hatred of Opaka. The two paintings reflect the people's simple choices in Bimini: either follow the rules set forth by Diaz and live forever or die. The plant, as it turns out, is poisonous and serves as the execution instrument. Shadwin and his friends, like the inhabitants of Bimini, decide to drink the water, just as Pullman's workers agreed to his demands to regulate their lives. All wanted to survive the depression of 1893.

However, the economy affected Pullman, also, and as demand for his luxury railroad cars plummeted, his revenues dropped. That winter, the businessman laid off two-thirds of his force and began cutting the remaining workers' wages, ultimately lowering them twenty-five percent. He did not, however, decrease the rents or fees in the Pullman community. Workers discovered themselves making $9.07 a week and spending $9.00 on rent. When a delegation approached Pullman, he declined to speak with them. On May 11, the Pullman workers boycotted, and the plant closed. Several weeks passed, and Pullman refused to negotiate, so the American Railway Union, led by Eugene Debs, organized the largest strike in the nation's history. On June 26, ARU switchmen refused to switch trains with Pullman cars, paralyzing Chicago. Debs announced that if any switchman was fired, all union members would walk off their jobs. By June 30, 125,000 workers on twenty-nine railroads had quit, and supporters obstructed trains across the nation. Traffic stopped on every rail line west of Chicago. [17]

The railroads, organized under the General Managers Association, needed the assistance of federal troops, so they went to President Grover Cleveland, who replied that he would only send troops if requested by a governor. Illinois Governor John P. Altgeld supported the workers, but after the Blue Island workers joined the strike and set fire to the rail yards, Attorney General Richard Olney obtained an injunction from a federal court, which enraged the strikers and increased hostilities. While the General Managers Association flooded the newspapers with stories about union lawlessness, President Cleveland sent 12,000 army troops (½ of the entire U.S. army at the time) to Chicago under the premise that it interfered with the federal mail and threatened public safety. More violence ensued, and ultimately, thirteen strikers were killed and fifty-seven injured. [18] In the aftermath, Pullman would only hire workers who promised not to join a union, rents were not lowered, wages remained reduced, and strikers were blacklisted across the United States. Debs and other leaders were sentenced to jail for contempt, and by the time they emerged from jail, the union no longer existed.

Peattie alludes to the results of the Pullman Strike her tale. Shadwin and his friends lead a rebellion against Diaz and Padre Anton when the two tyrants accuse Opaka of sedition for teaching the young people to read, write, and think. She will be tried before the councilmen the next day. The friends arrange an audience with the governor to plead her cause, but it ends in angry words. They organize four hundred of Opaka's students and De Vega's laborers, and they march to the State House to lay siege. A delegation meets with the governor, but returns with the message that the patriarch "will not change his decrees, nor alter his designs. . . .she shall die the death" the next day at sunrise. A battle erupts against the men of Bimini, who consider the protesters "the enemies of good order and religion." The fighting extends even up to the waters of the Fountain, where the "young, splendid men, who would never know age or pain, died like sheep," turning the waters of life red with their mingled blood. Shadwin is injured, and when he awakens, he learns that his friend Bridges is dead, the cause is lost, and Opaka has been executed. Bryan and Shadwin, upon learning they have been summoned to the State House, flee Bimini rather than face execution. Like the Pullman strikers, the Bimini rebels are hugely outnumbered by the government forces, and the leaders resume their patriarchal control over the residents, but now with no one to teach them about "nature, truth, humanity, and even evil." They will revert to "simple and perplexing creatures" who live in the present and "think so little." Only Shadwin survives the dangerous journey home. When he returns, no one believes his story and accuses him of being responsible for the deaths of his friends. In the end, he wanders the earth, never aging but wanting to die. Even he wonders, "Am I not the victim of a gigantic illusion?"

An outspoken activist in American society and politics, I believe that Peattie alludes to the Pullman strike in her utopian novel "A Fountain of Youth" to criticize the inhumanity of large corporations such as Pullman and to illustrate the abuses of a paternalistic society. As former resident of Chicago, she took special interest in the events taking place there; when it moved into her back yard in Omaha, she saw its effects first hand. She warns her readers that no perfect world exists, that freedom of expression and liberty are truths to die for, and that we must not be like Shadwin and doubt our ideals. Peattie's novel of an oppressive dictatorship mirrored the sentiments of people across the United States, for in 1894, a national commission studied the causes of the strike and declared that Pullman's paternalism shouldered much of the blame and that the company town of Pullman was "un-American." [19]

In answer to Peattie's philosophical question–"If the Fountain of Youth bubbled up before you and you knew that by drinking of its waters you would live forever, would you drink it?"–I believe that her answer would be emphatically "No." Even if a perfect land existed with miraculous waters, mankind (or, perhaps, even more specifically, men), would spoil it because of human imperfection.

References

Bassett, Jonathan. "The Pullman Strike of 1894." OAH Magazine of History. 11.2 (Winter 1997): 34.

Brendel, Martina. "The Pullman Strike." Illinois History: A Magazine for Young People (December 1994): 8-9. Illinois Periodicals Online. 16 August 2008 http://www.lib.niu.edu/1994/ihy941208.html.

Grey, Christopher and Christina Garsten. "Organized and Disorganized Utopias: An Essay on Presumption." Utopia and Organization. Ed. Martin Parker. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers, 2002. 9-23.

Illinois Labor Historical Society. "The Parable of Pullman." 16 August 2008 http://www.kentlaw.edu/ilhs/pullpar.htm.

Ladd, Keith and Greg Rickman. "The Pullman Strike: Chicago 1894." 3 March 1998. 16 August 2008 http://www.kansasheritage.org/pullman/index.html.

Lillibridge, Robert M. "Pullman: Town Development in the Era of Eclecticism." The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 12.3 (Oct. 1953): 17-22.

Lindsey, Almont. "Paternalism and the Pullman Strike." The American Historical Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, (Jan., 1939), pp. 272-289.

Peattie, Elia W. The Wonderful Story of America. Chicago: International Publishing Co, 1895.

Pullman State Historic Site. August 2008. 5 December 2008 http://www.pullman-museum.org/wordpress/?p=12.

Reiff, Janice L. and Susan E. Hirsch. "Pullman and Its Public: Image and Aim in Making and Interpreting History." The Public Historian: Labor History and Public History 11.4 (Autumn, 1989): 99-112.

Roemer, Kenneth M. The Obsolete Necessity: America in Utopian Writings, 1888-1900. Kent, OH: Kent State University press, 1976.

Steinhoff, William. "Utopia Reconsidered: Comments on 1984." No Place Else: Explorations in Utopian and Dystopian Fiction. Eds. Rabkin, Eric S., Martin H. Greenburg, and Joseph D. Olander. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1983. 147-161.

Woodward, Kathleen. "On Aggression: William Golding's Lord of the Flies." No Place Else: Explorations in Utopian and Dystopian Fiction. Eds. Rabkin, Eric S., Martin H. Greenburg, and Joseph D. Olander. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1983. 199-224.

Illustrations

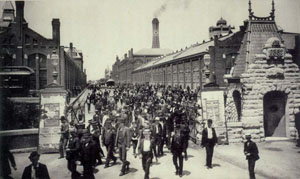

"Pullman Strikers." www.vw.vccs.edu/vwhansd/his122/Debs.html. (Public Domain.)

"George Pullman 1890." http://www.pullman-museum.org. Courtesy Bertha Ludlam Research and Archive Collection, Pullman State Historic Site.

"Arcade Row Houses." http://www.pullman-museum.org. Courtesy Bertha Ludlam Research and Archive Collection, Pullman State Historic Site.

"Pullman Theater Interior." http://www.pullman-museum.org. Courtesy Bertha Ludlam Research and Archive Collection, Pullman State Historic Site.

"Arcade Library Interior." http://www.pullman-museum.org. Courtesy Bertha Ludlam Research and Archive Collection, Pullman State Historic Site.

"Moveable Mansion." http://www.pullman-museum.org. Courtesy Bertha Ludlam Research and Archive Collection, Pullman State Historic Site.

"Pullman Troops." http://www.vw.vccs.edu/vwhansd/his122/Debs.html. (Public Domain.)

Notes

XML: ep.nov.foy.pa.xml