Who Is the "New Woman"?

During the 1890s the Victorian ideal of femininity, the "True Woman," gradually yielded to a female figure of considerably greater authority: the "New Woman." The four cardinal values of purity, piety, domesticity, and submissiveness, ingrained in women's minds for nearly a century, seemed less relevant to the changing climate of the Progressive Era. New Women both looked and behaved differently than women of the Victorian Era and in general mapped their own futures according to their individual desires and needs. New Women also spoke in a voice never before heard in American society, postulating "intellectual, social, and verbal equality between men and women. They rode bicycles while wearing bloomers, sought the vote, advanced schooling, and public sector jobs as necessary, and in general mapped their own futures according to their desires and needs. New Women also spoke in a voice never before heard in American society: they "postulated intellectual, social, and verbal equality between men and women." [1] New Women did not seek the sanction of male authority to legitimize their beliefs but asked that feminine views be considered on the same level as men's. [2]

Indeed the role of women in society had been undergoing drastic revision ever since the economic landscape of the country had begun to change during the Civil War. During the decade of the War, companies involved in the manufacture of goods increased by 79.6 percent, which in turn boosted the number of workers hired by 56.6 percent. [3] Writes historian Howard Zinn, "between the Civil War and 1900, steam and electricity replaced human muscle, iron replaced wood, and steam replaced iron. Machines could now drive steel tools . . .people and goods could move by railroad. The telephone, the typewriter, and the adding machine speeded up the work of business." [4] All these changes created thousands of new jobs, many of which would be filled by women.

At the same time that they were joining the country's labor force, women were establishing themselves as agents of social change as they participated in municipal housekeeping. Their presence alongside men in the public sector underscored the worth of women's contributions outside the home. The perception that women need define themselves primarily in relation to their husbands and children was beginning to change.

Peattie encouraged women to contribute to their evolving communities by developing informed political views. "I insist that women have a moral responsibility resting upon them to know [about political] things," she wrote in 1892. "The truth is that there is no subject which God has yet permitted man to mine from the vast mountains of knowledge that a woman cannot understand if she tries. It seems so pitiful that it should be necessary to say that!" [5]

Carrie Chapman Catt, an educator who also organized the National American Woman Suffrage Association and later the League of Human Voters, described the emergence of the "New Woman" in a NAWSA presidential address in 1902:

"When at last the New Woman came, bearing her torch of truth, and with calm dignity asked a share in the world's education, opportunities, and duties, it is no wonder that [some] shrunk away in horror . . . the whole aim of the woman movement has been to destroy the idea that obedience is necessary to women; to train women to such self-respect that they would not grant obedience and to train men to such comprehension of equity that they would not exact it [sic] . . ." [6]

Peattie echoed Catt's beliefs, adding, "I'm not urging you to become agitators, and neglectors of babies, and loud-voiced harpers on tiresome and impossible reforms, but I'm asking you to formulate your ideas and not be so vacuous." [7]

Who is the "New Woman?"

- Prairie Domesticity

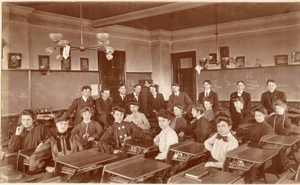

- Educating Children on the Plains

- Bicycles, Bloomers, and the New Woman

- Workplace of Women

References

Cutter, Martha J. Unruly Tongue: Identity and Voice in American Women's Writing, 1850-1930. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1999.

Freeman, Susan K. "The New Woman." Clash of Cultures in the 1910s and 1920s. Department of History. Ohio State University. Website accessed: 2/20/08 http://ehistory.osu.edu/osu/mmh/clash/NewWoman/opposition-page1.htm.

Johnson, Paul. A History of the American People. New York: Harper Collins, 1998.

Peattie, Elia. "The Women and Politics: They are Too Proud to Worship a Name-Most are Republicans-They Should Understand the Rudiments of Politics for They Have Grave Responsibilities." Omaha World-Herald. 11/20/92: 13.

Ravith, Diane. The American Reader: Words That Moved a Nation. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991.

Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper Collins, 2003.

Illustrations

"Gibson Girls." Courtesy Carrie Crockett.

"Class of 1903." Courtesy Carrie Crockett.

Notes

XML: ep.owh.wom.0001.xml