HOLLYWOOD INDIANS

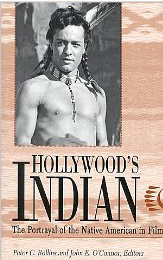

Hollywood's Indian: The Portrayal of Native Americans on Film, by Peter C. Rollins and John E. O'Connor, eds.

In more than a century of film history, the "Hollywood Indian" has rarely reflected the actual Native Americans of the Great Plains. During the years of silent film production, Native Americans were often played by members of the Sioux Nation. "Extras" were brought in by busload for the films, and producer and director Thomas Ince had a Sioux settlement of "Ince Indians" on the California coast. Even during those years, however, Native American roles of importance were generally played by non-Native actors, and the dress and customs of Native American peoples were depicted in whatever costumes suited the director or set designer's taste and rarely reflected the individual tribes. However, the Hollywood Indian from the 1920s through the 1980s was more likely to resemble a Plains Indian than any other, largely because the American audience quickly grew accustomed to the exotic look of Plains headdresses and breastplates. In 1914, Alanson Skinner, assistant curator of the Department of Anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History, wrote the New York Times to complain about these inaccuracies in film costuming, describing the movies as "grotesque farces" in which Delawares were dressed as Sioux and eastern Indians were shown dwelling in skin tipis of the type used only in the trans-Mississippi West.

In 1940 a Cherokee actor named Victor Daniels (aka Chief Thunder Cloud) led a group of actors in applying to the Bureau of Indian Affairs for recognition as the "De Mille Indians," a new tribe composed only of Native Americans who worked in the film industry. While humorous, the application was also an attempt to show the artificiality of the stereotypes found in the film images. The Western imagination is largely visual, and American audiences have over the course of film history generally accepted as reality the Hollywood Indian, whether Noble Savage or Bloodthirsty Savage.

The Native American has often been used as the metaphorical foe in Westerns. For instance, when the Colonel William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) Historical Pictures Company made The Indian Wars in 1914, the secretary of state sent troops and equipment for the filming, Gen. Nelson Miles agreed to appear in the film, and the War Department put the Pine Ridge Sioux (Lakota) at Cody's disposal. Such overwhelming support was due, presumably, to the fact that the film was to be used for War Department records and to enlist recruits to fight in World War I. Later, films such as Northwest Passage (1939) would be similarly used to engender a patriotic response in World War II, with the Hollywood Indian standing in for the German soldiers once more.

During the 1950s the images were more likely to be those of the Noble Savage, as Hollywood, experiencing the effects of Mc- Carthyism, used the Native American to represent the oppressed Other. Broken Arrow (1950) and Cheyenne Autumn (1964) showed the Native American as gallant and dignified in the face of oppression by the dominant culture. Little Big Man (1970) and Soldier Blue (1970) used Native Americans as metaphors for the Vietnamese, with the message that innocent and noble people were being killed in an unjust war.

Perhaps the most obvious Hollywood Indian appeared in Elliot Silverstein's 1970 film A Man Called Horse, which was intended and well publicized as a "sympathetic and accurate portrayal" of the Plains Indians, particularly the Lakota Sioux. However, according to Ward Churchill, a Native American scholar, the film depicted Indians whose language was Lakota, whose hairstyles ranged from Assiniboine to Nez Perce to Comanche, whose tipis were Crow, and whose Sun Dance ceremony was Mandan. Other important distortions include sending an old woman out into a blizzard to die because her only means of support, her son, was killed in a raid. This is in direct opposition to the reverence with which the Sioux peoples hold the elderly.

The Hollywood Indian of the 1980s and 1990s is more likely to be an actual Native American than in previous decades, and a few films have been made that depict Native Americans less stereotypically, although many still include stereotypes old and new (the Natural Ecologist is among the new ones). Although most films that include Native Americans still take place in the past with tribes that are vanishing or have vanished (as the scroll at the end of Kevin Costner's 1990 Dances with Wolves indicates), the images of Native America are occasionally more human than stereotypical. Also, more films are being made by Native American filmmakers, so perhaps it is the Hollywood Indian tribe that will soon vanish.

Jacquelyn Kilpatrick Governors State University

Bataille, Gretchen, and Charles L. P. Silet, eds. The Pretend Indians: Images of Native Americans in the Movies. Ames: Iowa University Press, 1980.

Churchill, Ward, and Annettee Jaimes. Fantasies of the Master Race: Literature, Cinema and the Colonization of American Indians. Monroe ME: Common Courage Press, 1992.

Kilpatrick, Jacquelyn. Celluloid Indians: Native Americans in Film. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

Previous: Harlow, Jean | Contents | Next: Hopper, Dennis

XML: egp.fil.029.xml