BLACK ELK, NICHOLAS (1866-1950)

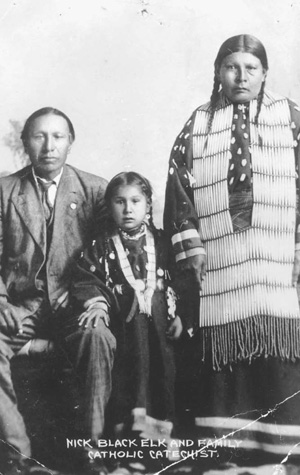

Nicholas Black Elk and family, between 1890 and 1910

View largerBlack Elk was probably the most influential Native American leader of the twentieth century. His influence flows from the enduring beauty and power of his religious teachings, his lifetime of engagement with the problems of his people, and the galvanizing effect of the book Black Elk Speaks on the revival of traditional religion and culture.

Black Elk was probably born in 1866, the first year after the Civil War. The end of the war brought western expansion, which led to aggressive efforts to confine and assimilate the Plains tribes. Black Elk's early years were spent living the old nomadic life, and he was present at the Custer fight on the Little Big Horn in 1876. He announced his vocation as a holy man by performing the Horse Dance in 1881, but after the government outlawed the Sun Dance and Native healing practices in 1883, his profession could only be practiced underground. Almost all Black Elk's working life as a holy man was spent in this repressive context, and his religious thought is in part a response to the dominant culture's oppression, missioniza tion, and social engineering. In 1887 Black Elk enlisted with Buffalo Bill Cody and traveled to Europe with his Wild West Show. On his return to the Pine Ridge Reservation in 1889, he became a leader of the Ghost Dance. When the government responded with troops, Black Elk called for armed resistance, and he was present at the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890.

After Wounded Knee, Black Elk seems to have continued with his medicine practice. In 1904 he accepted Catholicism and became active as a catechist, a position that allowed him to regain a public leadership role. He mastered reservation Catholicism through conversations with the Jesuits, including Eugene Buechel, who cites Black Elk in his Lakota dictionary. In 1931 Black Elk was interviewed by poet John G. Neihardt, which resulted in Black Elk Speaks (1932). The book strained Black Elk's relationship with the Jesuits, and he subsequently worked at the Duhamel Sioux Pageant, demonstrating traditional rituals. In 1944 Neihardt interviewed Black Elk for When the Tree Flowered (1951). In 1947–48 Black Elk gave an account of Lakota ritual to Joseph Epes Brown that became The Sacred Pipe (1953), which provides a Lakota parallel to the seven sacraments and asserts the equal validity of Christianity and traditional religion. Black Elk died at Manderson, South Dakota, on August 17, 1950.

Scholarly work on Black Elk has tended to focus on the authenticity and adequacy of Neihardt's portrait of Black Elk as a traditionalist in Black Elk Speaks and on the related issue of the extent of Black Elk's commitment to Catholicism. (The authenticity of The Sacred Pipe is a growing topic of discussion.) At one pole of the debate, Michael F. Steltenkamp's Black Elk: Holy Man of the Oglala (1993) portrays Black Elk as a progressive Catholic who retains little meaningful commitment to traditional religion. At the other pole, Julian Rice's Black Elk's Story: Distinguishing Its Lakota Purpose (1991) portrays Black Elk's involvement in Catholicism as strategic, a response to oppression. Although this debate is illuminating, it is also misleading, because Black Elk retained a lifelong commitment to the central intention of the Ghost Dance, the revitalization of traditional culture through religious ritual. In terms of culture, Black Elk was undoubtedly a nativist, and the symbolism and hope of the Ghost Dance is seldom far from his teaching. On the other hand, his engagement with Catholicism shows that he could assimilate a very different set of religious symbols, something that seems to have been far easier for him than for academic observers obsessed with the colonialist search for authenticity.

Black Elk was not the broken old man who mourns the death of the dream at the end of Black Elk Speaks. Nor was he anybody's anthropological informant, a passive source of information on the past. For Black Elk, the dream never died, and he always spoke to the Lakota present. In the simplest terms, he was a leader of his people during a time of troubles, and those troubles should certainly not be forgotten in evaluating his life and work. Black Elk was one of the most gifted spokesmen for the Lakota wisdom tradition, and his farseeing literary collaborations have disseminated his teachings far beyond their original cultural horizon. Lakota holy men still teach the great lessons of this tradition–respect for sacred power, the relatedness of all beings, and care for the earth–and they still draw on Black Elk's legacy, which continues to confront and challenge European ways of viewing humanity, society, and the cosmos.

See also LITERARY TRADITIONS: Neihardt, John G. / WAR: Wounded Knee Massacre.

Clyde Holler Morganton, Georgia

DeMallie, Raymond J., ed. The Sixth Grandfather: Black Elk's Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

Holler, Clyde. Black Elk's Religion: The Sun Dance and Lakota Catholicism. Syracuse NY: Syracuse University Press, 1995.

Holler, Clyde, ed. The Black Elk Reader. Syracuse NY: Syracuse University Press, 2000.

XML: egp.rel.005.xml