ASIAN AMERICANS

In 1870 the first "Chinaman" set foot on the streets of Denver, Colorado. A local paper described him as "short, fat, round-faced, almond-eyed beauty," and added that he "appeared quite happy to get among civilized people." Despite this kind of ridicule, the Chinese of Denver soon became an essential element in the city's urban economy. They provided domestic services to a primarily male population for an affordable price, services that had not been available before the Chinese arrival. From that time on, the Asian presence in Denver and in many other parts of the Great Plains has been a permanent fixture.

But if one were to open a Denver history book, or any history book about the Great Plains for that matter, one would be hardpressed to find more than one or two pages written on Asians. This marginalization from the pages of history is a clear injustice to a people who have been fundamental to the development of the region. From the late-nineteenth-century Chinese, who did the vast majority of the region's laundry, to the present-day Southeast Asians who have revitalized city neighborhoods and provided a workforce for the region's meatpacking industry, Asians have made and continue to make vital contributions to the prosperity and growth of the Great Plains.

Chinese Pioneers

The Chinese were the first Asian immigrant group to reach the region. Settling originally in the California goldfields, they began moving eastward in the 1860s following railroad construction and mining opportunities. From California they moved to Nevada, Montana, Wyoming, and then Colorado. Although the first Chinese came to the Western Plains to work on the railroads and in the mines, the vast majority who followed these pioneers came to fill the empty economic niche in laundry work and other domestic services, a necessity in the rough-and-tumble, predominantly male frontier towns. By 1880, for example, Denver had a thriving Chinese community of 238, of whom more than 80 percent worked as laundrymen. In other towns such as Deadwood, South Dakota, Chinese opened restaurants, general provision stores, and opium dens. The Plains' Chinese population gradually began to move farther east, providing similar urban services along the way. By 1890 there were 224 Chinese in Nebraska, and by 1920, 261 had settled in Oklahoma.

Chinese also migrated to the Prairie Provinces of Canada. The majority settled in large cities such as Edmonton and Calgary, Alberta, while others settled in smaller urban communities such as Lethbridge and Medicine Hat, Alberta. Many were brought in by American contractors (especially the Minnesota firm of Langdon and Shepard) to lay the tracks of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the years 1881 to 1883. Many of the laborers were recruited directly from the United States, and some returned to the United States after the contract ended. After 1883 the Canadian Pacific Railway recruited directly from Canton and Hong Kong, as well as from Vancouver. By 1900 Calgary had become home to approximately eighty Chinese who worked as laborers, cooks, and domestic servants.

Despite being invaluable to the Great Plains urban economy, the Chinese were still subject to discrimination. White workers blamed Chinese for the slow economy and resented Chinese competition, particularly in the mining industry. Politicians stoked this volatile issue in order to gain the labor vote. As a result, towns often practiced discriminatory taxation and passed economic sanctions against the Chinese.

There were times when these discriminatory measures did not satisfy a town's populace and violence ensued. On Sunday, October 31, 1880, for example, a group of several hundred white males incited an anti-Chinese riot that resulted in the death of one laundryman and the destruction of Denver's Hop Alley. The immediate cause was a bar fight between two Chinese and two whites, but the underlying cause was the anti-Chinese agitation of the local Democratic Party and labor organizations. A similar incident occurred in Calgary. On August 2, 1892, a mob of more than 300 destroyed Chinese laundries after learning that four Chinese who had been quarantined for smallpox had been released. In both cases, authorities were exceedingly slow to react.

The best-known and bloodiest action against the Chinese in, or near, the Great Plains occurred in September of 1885 in Rock Springs, Wyoming. A few months earlier, the Union Pacific Coal Division had brought in about 300 Chinese to work in the local mines, an action that infuriated local white workers. On September 2, two white miners found that the seam to which they had been assigned was already being tapped by two Chinese miners. The enraged miners proceeded to rally other white miners, and by early afternoon a mob of 150 moved on Rock Springs' Chinatown, slaughtering residents at every opportunity. At day's end, twenty-six Chinese were dead and fifteen others were wounded. Government troops eventually restored order and helped company officials to reinstate Chinese in the mines. To this day, the Rock Springs massacre stands as one of the most brutal manifestations of American opposition to the Chinese presence.

The Chinese were not always passive in the face of such oppression. They used the legal system as a means of resistance and sometimes even won their cases. In 1882, for example, local authorities accused Yee Shun of murdering a fellow Chinese in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Although the court eventually found Yee Shun guilty, the defense team achieved a legal victory of immense proportions for all Chinese in America. They were able to overturn a prior ruling prohibiting Chinese from testifying in court.

Another legal victory for the Chinese occurred in Regina, Saskatchewan, in 1907. On the morning of August 8, nine patrons of the Capital Restaurant became ill after eating porridge. Local authorities soon discovered that Charlie Mack, the Chinese cook of a competing restaurant, had poisoned the porridge. Mack disappeared before he could be arrested, causing the local authorities to detain the entire male Chinese population of Regina in an effort to extract information concerning his whereabouts. The Chinese, encouraged by their lawyers, prosecuted the local officials. They won their case, received a small indemnity, and had the satisfaction of seeing Regina's police chief removed from office.

By 1890 the Chinese population in the Great Plains had peaked. Every state, territory, and province in the region had Chinese residents. Soon afterward, however, this population began to decline, especially in Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana, the states where the largest settlements had been concentrated. The decline followed a national trend that had begun with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and continued in the early twentieth century with the passage of the 1902 Chinese Exclusion Act, a congressional bill that made permanent the 1882 act. Because most Chinese in the United States, including the Great Plains, were male, and because immigration had been banned, there was little natural population growth. Under the circumstances, community roots never had a chance to take hold, and they withered quickly after 1902. Similarly, Canada imposed restrictions on Chinese immigration in 1903 and 1923. The legislation virtually halted Chinese immigration until 1947, when it was repealed.

Japanese: From Farms to Internment

With the decline in the Chinese population, industrialists and growers needed a new source of cheap labor. They turned to newly arrived Japanese immigrants. Between 1880 and 1900, yearly Japanese immigration to the United States increased from 148 to 24,326. Although most Japanese settled in Hawaii and California, a good number moved to the Great Plains. Like the Chinese before them, the Japanese followed rail, mining, and agricultural work to Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. By 1910 Japanese migrants also began moving to Nebraska and Kansas to pursue sugar beet work and to coastal Texas to cultivate rice.

One immigrant, Naokichi Hokazano, was particularly instrumental in bringing Japanese to the Plains. Arriving in Denver in 1898, Hokazano promptly contracted seventy Japanese to harvest 1,200 acres of sugar beets that he owned. Hokazano has been criticized by Asian American historians for exploiting the labor of his countrymen by paying them substandard wages. Nevertheless, he was responsible, at least in part, for the increase in Japanese migration from the West Coast to the Great Plains. By 1909, of the 3,500 Japanese in Colorado, almost 2,000 were connected to the sugar beet industry.

Within twenty years, through skill, enterprise, and hard work, several of these immigrants became successful landowners and farmers, a pattern of upward mobility first seen in California. The Japanese in this economic sector were so successful that many competing white farmers gave up, leaving the industry open to further Japanese control. These pioneers of Colorado agriculture irrigated, and thus made arable, much of the land in the northeast corner of the state. Today, they are honored in the state capitol building, where Naokichi Hokazano is memorialized in a stained-glass window.

Japanese also started urban businesses and organized civic institutions. By 1916 they owned sixty-seven stores in Denver and had founded the Japanese Methodist Church and the Denver Buddhist Church. In Scottsbluff, hub of Nebraska's sugar beet industry, Japanese settlers started the Japanese-language newspaper Neshyu Jibo (Nebraska News) and founded the Japanese Association of Nebraska. In Texas, Japanese dominated the nursery industry.

Like the Chinese before them, Japanese also settled in the Prairie Provinces of Canada, moving into southern Alberta shortly after the turn of the century. They migrated mainly from British Columbia and the United States. As in the United States, they worked in the mines, on railways, and in agriculture and were quite often recruited by labor supply companies. In 1907 the Canadian Nippon Supply Company recruited a large group of Japanese to work in the mines near Lethbridge, Alberta. The following year, Nippon Supply sent 300 more workers to the Lethbridge mines. Unfair treatment by their employers and by fellow countrymen working for labor supply companies prompted Japanese laborers to organize labor unions soon after their arrival in the Prairie Provinces. It was not until the 1920s, however, that Japanese workers were accepted as equals, with equal pay, to white workers.

As in the American Great Plains, Japanese in the Prairie Provinces made their greatest contribution in agriculture. In 1907 the Canadian Pacific Railway recruited 370 Japanese workers through the Nippon Supply Company to build irrigation ditches. The Raymond Knight Sugar Company recruited 100 Japanese workers in 1908 and another 105 in 1909. The workers remained wage laborers for only a few years, however, as they soon began to lease and, on occasion, buy their own tracts of land. These successful Japanese pioneers eventually established permanent communities with their own newspapers, churches and temples, and social organizations.

Their success in farming prompted a more virulent racism. In the early 1920s, following the example of California, the states of Montana, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Texas passed legislation barring Japanese from owning or leasing land. Colorado was the only Plains state with a significant Japanese population that did not pass an alien land law. This was one reason why more Japanese moved to Colorado than elsewhere in the Great Plains, and why Japanese Coloradans were so successful in agriculture.

The worst act of discrimination perpetrated against Japanese Americans–an act that did not bring an o.cial apology from the United States until August 10, 1988–came during World War II. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 allowing for the internment of all Japanese within a designated militarized zone. While this zone was located primarily on the West Coast, "suspected" Japanese community leaders throughout the nation were also interned, including those in the Plains.

Rev. Hiram Hisanori Kano of Nebraska, for instance, was arrested on the day of the Pearl Harbor attack. He was held in a Santa Fe, New Mexico, internment camp until 1944. Kano and other community leaders were imprisoned merely on suspicion of disloyalty. Elsewhere in the Great Plains anti-Japanese hysteria led to house searches by the FBI, often carried out in a demeaning and destructive manner.

The Plains was the site of one of the largest internment camps in the United States, Granada, Colorado (also called Amache). Heart Mountain, Wyoming, another large camp, was just to the west of the Plains. Several smaller camps were also located in the region. At one such camp in Lordsburg, New Mexico, in the early morning of July 27, 1942, an army guard shot and killed Hirota Isamura and Toshira Kobata as they were being delivered for internment. The guard insisted that Isamura and Kobata were trying to escape, although several eyewitness accounts maintained otherwise. The guard went unpunished.

Meanwhile, as fellow Japanese Americans were being imprisoned, young nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans) served in the American military with distinction. One of them, Ben Kuroki of Hershey, Nebraska, came home with a distinguished war record only to find himself ostracized for being Japanese. This discrimination led Kuroki to campaign against the injustices of internment.

The long-overdue apology for internment came only after a hard-fought redress effort by Japanese Americans. Bill Hosokawa, a resident of Denver and himself a veteran of internment, was particularly instrumental in gaining this apology. Hosokawa was interned at Heart Mountain in Wyoming, where he published the camp newspaper. After his release Hosokawa became active in the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), the organization primarily responsible for redress. Hosokawa also became the Denver Post's first foreign correspondent, and he covered the Korean War in this capacity. Later in his career he became the Post's Sunday magazine editor and then the assistant managing editor. His career as a journalist made him JACL's selection to write a history of second-generation Japanese Americans called Nisei: The Quiet Americans (1969).

Hosokawa and the JACL are at the center of a five-decade-old controversy that has divided the Japanese American community. During the months preceding internment, the JACL took the stance that cooperation with the government's internment plans was a necessary evil that Japanese Americans would have to endure in order to demonstrate their loyalty. This stance has not been popular with the more militant members of the Japanese American population who argue that it was in essence a sellout. This controversy continues to this day and has been fervently taken up by third-generation Japanese Americans, the sansei.

Japanese Canadians were also persecuted during World War II, and again the Great Plains, securely in the heart of the country, was the setting for their forced relocation. In 1942, 20,881 Japanese, 75 percent of them Canadian citizens, were taken from their homes and moved to detention camps in the interior of British Columbia and to sugar beet farms in Manitoba and Alberta. Many of the relocated Japanese Canadians worked for individual farmers, but others were gathered into huge "prisoner of war" camps at Lethbridge and Medicine Hat. The Canadian government sold off their assets–farms, homes, fishing boats–and used the proceeds to finance the internment. At the end of the war, Japanese Canadians were given the choice of either returning to a devastated Japan or moving permanently to the Prairie Provinces or eastern Canada. Most chose the latter option.

The discrimination did not end with the war. In 1946 the Canadian government tried to deport 10,000 Japanese Canadians, and only an international outcry prevented this infamy. Japanese Canadians did not regain their status as Canadian citizens until 1949.

Late Twentieth-Century Developments

In 1965 the U.S. Congress passed an Immigration Reform Act. By removing racially based quotas, promoting family reunification as a priority, and encouraging the immigration of professionals, the act opened the way for a great increase in Asian immigration to the United States, including the Great Plains. As a result the Plains has experienced a recent influx of Filipinos, Koreans, Chinese, and South Asians (Indians and Pakistanis). Each of these ethnic groups has thriving communities in major Plains cities. In 2000 the Denver metropolitan area, for instance, had an Asian population of approximately 63,000, Dallas–Fort Worth had an Asian population of close to 195,480, and Oklahoma City had an Asian population of almost 18,000. Chinese and Koreans have played a significant role in reviving small businesses in urban areas. Filipinos have mainly entered the professional ranks. And Indians, in addition to being both shopkeepers and professionals, have built an occupational specialty in the small-motel industry. Chinese and Indians, in particular, are well represented in higher education and the high-technology industry.

Similar circumstances have resulted in a significant increase in Asian numbers in the Canadian Prairie Provinces. As of 1991 Alberta was home to 71,635 Chinese, 16,310 Filipinos, and 54,750 South Asians; Manitoba was home to 11,145, 22,045, and 24,465, respectively; and Saskatchewan was home to 7,550, 1,635, and 11,285, respectively. In recent years a large number of Chinese left Hong Kong in anticipation of the July 1997 takeover by the People's Republic of China. Canadian immigration policy encouraged the immigration of wealthy Hong Kong investors by granting automatic residency to any person investing $1 million in the Canadian economy. Most Asians have settled in urban areas, particularly Edmonton, Calgary, and Lethbridge. The presence of the Nikka Yuko Garden in Lethbridge, one of the most authentic Japanese gardens in North America, is visual evidence of the importance of the Japanese presence in the Prairie Provinces.

Also in the recent years, the Great Plains has attracted large numbers of refugees from Southeast Asia. Subsequent family reunification has swelled their numbers. Having been forced to flee their homelands due to war, several million have made new homes in the United States and Canada. They migrated in two waves, one in 1975 and the other starting in 1979 and continuing to the present. The first wave consisted primarily of the highly educated or professionals fleeing from Vietnam and, in smaller numbers, from Cambodia. By contrast, the 1979 wave consisted mostly of farmers and rural dwellers from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. While U.S. relief agencies intended to relocate these refugees to all parts of the nation, the majority have gathered in only a few states–California, Texas, Washington, Oregon, and Minnesota. Thus, although the Plains' Southeast Asian population is relatively small, it is growing and certainly an invaluable contributor to the region's social and economic fabric.

In at least four Plains cities–Denver, Oklahoma City, Tulsa, and Wichita–Southeast Asians have formed communities with populations of more than 1,000. These communities have started to form civic organizations that address the multiplicity of adjustment problems faced by refugees. The Oklahoma Vietnamese, for instance, formed the Vietnamese American Association (VAA) in 1978. To date the VAA has offered English classes and job training, placement, and upgrading services. The VAA has been so successful that the federal government has used it as a model for its national program.

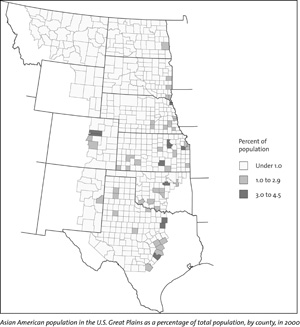

Asian American population in the U.S. Great Plains as a percentage of total population, by county, in 2000

View largerIn Denver, Southeast Asians have also formed community organizations. Led by a first-wave refugee, Khan Penn, the Cambodian community formed the Colorado Cambodian Community (CCC) in 1976. The CCC emphasizes the preservation and observation of cultural traditions and revolves to a large extent around the Buddhist temple. These sorts of community activities also serve to ease the adjustment of Cambodian refugees although not in as concrete a manner as the VAA in Oklahoma City.

Southeast Asians have noticeably affected the demographic makeup of some Plains regions. For example, more than 100 Laotians settled in the small town of Tecumseh, Nebraska, between 1982 and 1992. In the late 1990s they accounted for about 6 percent of the town's population and more than 17 percent of its schoolchildren. Refugees often move to small towns like Tecumseh in order to escape the more economically competitive environments of large cities. In many instances they are also recruited by local industries, such as Tecumseh's Campbell Soup canning factory. Garden City, Kansas, has seen similar changes as more than 1,000 Vietnamese migrated into the city, mainly to work in local meatpacking companies.

Southeast Asian numbers in the Plains are growing at a rapid rate. In Colorado, for instance, 7,210 Vietnamese, 1,320 Cambodians, 1,202 Hmong, and 1,996 Laotians were noted in the 1990 census. More than 97 percent of these groups lived in urban areas, particularly in Denver. Similar situations can be found in Nebraska although on a smaller scale. More than 2,600 Southeast Asians lived in the state in 1990, of whom 1,800 were Vietnamese. The Vietnamese numbers grew to 6,364 by 2000. In Colorado, according to the 2000 census, Vietnamese were the second-largest Asian ethnic group after Koreans. In Kansas the Vietnamese population of 11,623 (2000) made it the single largest Asian ethnic group. In 2000 the total Southeast Asian population in Kansas numbered more than 15,000. A similar demographic situation existed in Oklahoma. There, the Vietnamese numbered 12,566 in 2000, with the total Southeast Asian population amounting to more than 15,000.

The significant numbers of Southeast Asians have not only revitalized the meatpacking industry and other labor-intensive industries in the Plains but have also reenergized key segments of urban economies. In Denver, for instance, the entrepreneurial drive of Vietnamese refugees invigorated a slumping Chinatown economy. They opened new restaurants and groceries, an immigrant entrepreneurial staple, and they own and operate beauty parlors, nightclubs, coffee shops, and jewelry stores, to name only a few enterprises. Southeast Asians have also contributed significantly to the success of Denver's high-tech industry. A large number, if not a majority, of assembly-line workers in this industry are Southeast Asian.

Asian Americans have clearly played a significant if not always acknowledged role in the history of the American and Canadian Great Plains. This role dates back to the time of Chinese railroad construction workers and miners and Japanese agricultural laborers. Today, although Asian Americans constitute no more than 5 percent of the population of any Great Plains county, Asian Americans are essential to the regional economy. Southeast Asians are contributing to the growth of communities that otherwise might be declining, and in urban areas such as Denver, Colorado, and Lethbridge, Alberta, Asian Americans are contributing to the rejuvenation of the urban economy. Asian Americans have been, and will continue to be, integral actors in the history of the Great Plains.

Malcolm Yeung

Evelyn Hu-DeHart

University of Colorado at BoulderBarth, Gunther. Bitter Strength: A History of the Chinese in the United States, 1850-1870. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964.

Culley, John J. "Trouble at the Lordsburg Internment Camp." New Mexico Historical Review 60 (1985): 225-48.

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps, North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada during World War II. Malabar FL: R. E. Krieger Publishing Co., 1989.

Fairbairn, Kenneth J., and Hafiza Khatun. "Residential Segregation and the Intra-Urban Migration of South Asians in Edmonton." Canadian Ethnic Studies 21 (1989): 45-64.

Ichioka, Yuji. The Issei: The World of the First Generation Japanese, 1885-1924. New York: Free Press, 1988.

Iwaasa, David. "Canadian Japanese in Southern Alberta: 1905 through 1945." In Two Monographs on Japanese Canadians, edited by Roger Daniels. New York: Arno Press, 1978.

Kano, Hiram Hisanori. A History of the Japanese in Nebraska, edited by Jean and Sheryll Patterson-Black. Scottsbluff NE: Scottsbluff Public Library, 1984.

Muzney, Charles C. The Vietnamese in Oklahoma City: A Study in Ethnic Change. New York: AMS Press, Inc., 1989.

Ralph, Martin G. Boy from Nebraska: The Story of Ben Kuroki. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1946.

Sontag, Deborah. "New Immigrants Test Nation's Heartland." New York Times, October 18, 1993.

Storti, Craig. Incident at Bitter Creek: The Story of the Rock Springs Chinese Massacre. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1991.

Takaki, Ronald T. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Boston: Little, Brown, 1989.

Wortman, Roy. "Denver's Anti-Chinese Riot, 1880." Colorado Magazine 42 (1965): 275-91.

Wunder, John R. "Law and the Chinese in Frontier Montana." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 30 (1980): 18-31.

XML: egp.asam.001.xml