ALL-BLACK TOWNS

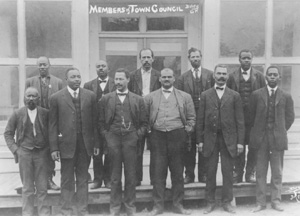

Town council, Boley, Oklahoma, ca. 1907–10

View largerAfrican Americans left the South for the "promised land" of the West in ever-increasing numbers after the Civil War. Economic hardship, racial violence, and intolerance prompted this vast migration from states such as Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, Texas, and Arkansas. With leadership from Pap Singleton and Henry Adams, the "Exodusters" settled mainly in Kansas in 1879–80, though the movement had began a few years earlier and lasted into the next decade. The opportunity to own land attracted many of these people to the Great Plains. Reports directed back to the South claimed that landownership was a simple and cheap prospect.

By 1881 African Americans emigrants had established twelve agricultural colonies in Kansas: Nicodemus, Hodgeman, Morton City, Dunlap, Kansas City–area Colony, Parsons, Wabaunsee, Summit Township, Topeka-area Colony, Burlington, Little Coney, and the Daniel Votaw Colony. Another settlement, the Singleton Colony, seems to have never really been a viable community. Many of the other colonies lasted only a few years. The town of Nicodemus, on the other hand, founded a few years before the large exodus, prospered into the twentieth century. African Americans also established colonies in Nebraska, including the town of Dewitty. They migrated to western New Mexico, too, creating settlements such as Blackdom and Dora. Oliver Toussaint Jackson established the settlement of Dearfield, Colorado, in 1910, one of the last African American Plains agricultural communities. Many African Americans dispersed elsewhere throughout the Plains; most worked the land like their white counterparts.

During a fifty-five-year period following the end of the Civil War, African Americans built more than fifty identifiable communities in Oklahoma. Some sprouted and quickly vanished; others still survive. Achieving freedom after the Civil War, former slaves of the Cherokees, Creeks, Seminoles, Chickasaws, and Choctaws also formed towns in Indian Territory. When the U.S. government allotted land to individual Native Americans, most Indian "freedman" chose land next to other African Americans. Their farming communities sheltered self-governed economic and social institutions, including businesses, schools, and churches. Enterprising businessmen set up every imaginable kind of business, including publishing concerns whose newspapers advertised in the South for settlers.

More African Americans settled in Oklahoma Territory with the land run of 1889, which ordered "free land" to non-Indians. E. P. McCabe, former state auditor of Kansas, helped found the all-black town of Langston. By means of the Langston City Herald, which his traveling agents circulated around the South, he and other leaders hoped to bring in large numbers of African Americans whose growing political power would secure their prosperity and safety. McCabe never accomplished his goal of creating an African American state. Nevertheless, dozens of black communities sprouted and flourished in the rich topsoil of the new territory and, after 1907, the new state.

In Oklahoma and Kansas, African Americans lived relatively free from the prejudices and brutality common in racially mixed communities of the Midwest and the South. Cohesive all-black settlements offered residents the security of depending on neighbors for financial assistance and the economic opportunity provided by access to open markets for their crops.

Marshalltown, North Fork Colored, Canadian Town, and Arkansas Colored existed as early as the 1860s in Indian Territory. Other Indian Territory towns that no longer exist include Sanders, Mabelle, Wiley, Homer, Huttonville, Lee, and Rentie. Among the Oklahoma Territory towns that no longer exist are Lincoln, Cimarron City, Bailey, Zion, Emanuel, Udora, and Douglas in old Oklahoma Territory. Surviving towns include Boley, Brooksville, Clearview, Grayson, Langston, Lima, Redbird, Rentiesville, Summit, Taft, Tatums, Tullahassee, and Vernon. Boley, the largest and most renowned of these was twice inspected by African American educator Booker T. Washington, who lauded the town in Outlook Magazine in 1908.

Immediately after statehood in 1907 the Oklahoma legislature passed Jim Crow laws, and many African Americans became disenchanted with the new state. A large contingent relocated to western Canada, forming colonies such as Amber Valley, Alberta, and Maidstone, Saskatchewan. Another exodus of African Americans from the United States occurred with the "Back to Africa" movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A large group of Oklahomans joined the illfated Chief Sam expedition to Africa. Other Plains African Americans migrated to colonies in Mexico.

The collapse of the American farm economy in the 1920s and the advent of the Great Depression in 1929 spelled the end for most all-black communities. The all-black towns were, for the most part, small agricultural centers that gave nearby African American farmers a market for their cotton and other crops. The Depression devastated these towns, and residents moved west or migrated to metropolises where jobs might be found. Black towns dwindled to only a few residents.

As population dwindled, so too did the tax base. In the 1930s many railroads failed, isolating small towns from regional and national markets. This spelled the end of many of the black towns. During the Depression, whites denied credit to African Americans, creating an almost impossible situation for black farmers and businessmen. Even Boley, one of the most successful towns, declared bankruptcy in 1939. Today, only a few all-black towns survive, but their legacy of economic and political freedom is well remembered.

Larry O'Dell Oklahoma Historical Society

Crockett, Norman. The Black Towns. Lawrence: Regents Press of Kansas, 1979.

Hamilton, Kenneth Marvin. Black Towns and Profit: Promotion and Development in the Trans-Appalachian West, 1877–1915. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

Taylor, Quintard. In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528–1990. New York: W. W. Norton, 1998.

XML: egp.afam.006.xml