SUN DANCE

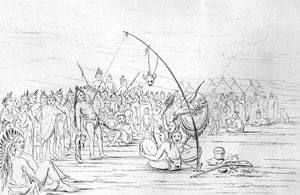

"INDIAN SUN DANCE: Native American Sioux Sun Dance, a man with his chest skin attached, with sinew, to a pole, drummers, spectators" by George Catlin

View largerThe Sun Dance is a distinctive ceremony that is central to the religious identity of the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains. It developed among the horse-mounted, bisonhunting nations who populated the Great Plains in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Those nations at the core of its practice in the bison-hunting era that have continued its practice into the contemporary period include the Arapahos, the Cheyennes (Southern and Northern), the Blackfoot (who include the Siksikas or Blackfoot proper, the Bloods or Kainahs, and the Northern and Southern Piegans or Pikunis), and the Sioux (including in particular the westernmost Sioux, who are the seven tribes of the Lakota nation, but also including the Yanktons and Santees, who comprise the six tribes of the Dakota nation). From these four nations, the Sun Dance ceremony spread to the Kiowas and Comanches, who ranged the Southern Plains, and to Northern Plains nations such as the Plains Crees of Saskatchewan and the Sarcees of Alberta, as well as to virtually every other Plains nation in the land between these two extremes, including the Arikaras, Assiniboines, Crows, Gros Ventres, Hidatsas, Mandans, Pawnees, Plains Ojibwas, Poncas, Shoshones, and Utes.

The Canadian and U.S. governments perceived this ceremony as superstitious rather than religious and suppressed it, and full liberty to practice the Sun Dance was regained only after the mid–twentieth century. Some Sun Dances, including the Kiowa, Comanche, and Crow ceremonies, ended in the nineteenth century. Others persisted clandestinely through the time of suppression. The Crows in 1941 formally renewed practice of the ceremony by receiving the Shoshone form as their own.

The name Sun Dance derives from the Sioux identification of it as Wi wanyang wacipi, translated as "sun gazing dance." Other Plains peoples have names for the ceremony that do not refer to the sun. The Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Blackfoot names for the ceremony all refer to the medicine lodge within which the ritual dancing occurs. The medicine lodge is constructed of pole rafters radiating from a sacred central pole. However, the best-known and most widely practiced contemporary form of the ceremony is that of the Sioux, who do not construct a medicine lodge. Instead, the Sioux make a hocoka, or ritual circle, with a sacred cottonwood tree erected in the center and a circular arbor built around the entire perimeter, except for an open entrance to the east, so that the dancing takes place within a central arena that is completely open to the sky and to "sun gazing." However, both traditions, whether that of the medicine lodge or of the hocoka, involve ritual ways of making local space sacred as a setting for renewal of the people's relationship with the land itself and with all the beings of their life-world, both human and other-than-human.

The ceremony is highly variable because its performance is intimately connected to the authoritative guidance of visions or dreams that establish an individual relationship between one or more of the central participants and one or more spirit persons. In all cases, however, the primary meaning is understood to be the performance of acts of sacrifice in ritual reciprocity with spiritual powers so that the welfare of friends, family, and the whole people is enhanced. The Arapaho, Cheyenne, Blackfoot, and Sioux nations all practice sacrificial acts of piercing the flesh, often described pejoratively as "torture" by outsiders. Others, such as the Ute, Shoshone, and Crow nations, perform sacrificial acts of embodying their spiritual intentions through fasting and intense dancing, but not through piercing.

Some Indigenous interpreters have suggested an analogy between the piercing of sun dancers and the piercing of Jesus on the cross, seeing both as acts of voluntary sacrifice on behalf of other beings and the cosmic welfare. While this interpretation may facilitate understanding for some, interpreters must be wary of imposing any religious category that clashes with the central concern of the Sun Dance: to establish and maintain kinship with all the people's relatives, including other humans, the animal and plant relatives of this earth, and the cosmic relatives of the spirit realm.

See also ARCHITECTURE: Native American Traditional Architecture.

Dale Stover University of Nebraska at Omaha

Densmore, Frances. Teton Sioux Music and Culture. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

Dorsey, George Amos. The Arapaho Sun Dance: The Ceremony of the Offerings Lodge. Field Columbian Museum Publication, no. 75. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 1903.

Farr, William E. The Reservation Blackfeet, 1882–1945: A Photographic History of Cultural Survival. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1986.

XML: egp.rel.046.xml