Roman Catholicism

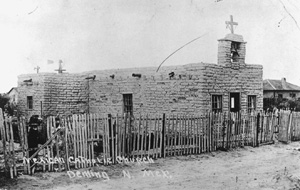

Mexican Catholic Church, Deming, New Mexico, 1910–1919

View largerRoman Catholicism was the first European church to be introduced into the Great Plains, and it remains the single largest denomination in the region. This reflects the diversity of Protestant denominations, of course, as well as the continued importance of Catholicism. But Catholicism in the Plains, as elsewhere in North America, is by no means homogeneous. At least through the middle of the twentieth century, it was an ethnically diverse church, and the various cultures of Catholicism in the region have much to do with the history of immigration.

As early as 1680, Spanish Franciscan missions lined the valley of the upper Rio Grande and spilled out onto the Great Plains to the east of Santa Fe. The number of these missions was reduced over the course of the following century, but Spaniards intermarried with Native Americans, and the religious legacy, reinforced by subsequent waves of Latino migrations in the 1920s, 1950s, and in recent decades, has persisted. In 1990, in almost all of the Plains counties of New Mexico and Colorado, Roman Catholicism is the largest denomination.

Spaniards, and Catholicism, did not extend significantly into the Southern Great Plains from the Franciscan missions that were established on the Gulf Coast Plain of Texas in the eighteenth century–the Comanches and Apaches formed a formidable barrier. Witness the destruction of Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá (built in 1757 at a site near present-day Menard, Texas) by a force of 2,000 Comanches and other Indians on March 16, 1758, which left two of the three Franciscan missionaries dead.

The next nucleus of Catholicism in the Great Plains emerged in the Red River Valley of the North in the early nineteenth century. In 1818 Lord Selkirk (Thomas Douglas) requested Catholic missionaries to serve his nascent colony of Scots, Irish, and Métis settlers. One of their number, Joseph-Norbert Provencher, was appointed bishop and apostolic vicar of the Northwest in 1820, and he later became the first bishop of St. Boniface. Alexandre-Antonin Taché, of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, followed Provencher to the Red River Settlement in 1845. Working as an assistant to Provencher, Taché was a tireless missionary to the Indians, Métis, and new settlers in the interior. He was appointed bishop of St. Boniface in 1853 and archbishop in 1871. Catholicism in the Prairie Provinces grew through conversion and in-migration of French Canadians and, later, eastern and southern Europeans. Roman Catholics remain the most numerous religious group in the Prairie Provinces, except for a belt of counties in southern Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, where the United Church of Canada predominates. Lac St. Anne, situated forty miles to the west of Edmonton, is the most important Catholic pilgrimage site in western Canada.

Roman Catholic missionaries were also active to the south of the forty-ninth parallel. The peripatetic Jesuit missionary Pierre-Jean De Smet began his work at the Saint Joseph's Mission to the Potawatomis at Council Bluffs in 1838, and he baptized thousands of Indians and Metis in the Northern Plains over the course of the next thirty years. In the Southern Plains, in present-day Kansas, Catholic missions were established for the Potawatomis (1838), Miamis (1847), and Osages (1847).

The ranks of Catholics in the Plains were greatly increased by immigrants after 1854—first Irish and Germans, then Germans from Russia, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians and others from eastern Europe, Italians, and most recently, Latinos. In North Dakota, Germans from Russia, clustering in the southcentral counties, were the most numerous Catholics. Germans from Russia also settled in Ellis County, in west-central Kansas, while Catholics from the Rhineland, Alsace, and Westphalia settled to the northwest of Wichita. Such clustering was encouraged by Louis Fink, bishop of Kansas, because it facilitated preaching and encouraged cohesion.

By the late nineteenth century, the Catholic Church in the Great Plains was divided into national parishes, which were distinct from official territorial parishes, though often under the same bishop. Italians, German Catholics, Irish, and others listened to services in their own languages and worshiped their own saints, continuing the traditions of their homelands. Even in the mid–twentieth century, such diverse expression prevailed. Integration has since occurred, with Hispanic Catholics remaining most distinct.

By 1890 Catholics ranked first in terms of religious adherents in the states of North Dakota (44.4 percent), Montana (77.5 percent), South Dakota (30.1 percent), Wyoming (61.4 percent), Colorado (54.3 percent), New Mexico (95.1 percent), and Nebraska (26.5 percent); second in Kansas (20.1 percent, behind Methodists) and Oklahoma (25.9 percent, behind Methodists); and third in Texas (14.7 percent, behind Baptists and Methodists).

A century later, Catholicism had lost ground to other denominations in much of the Plains, especially to Baptists in the Southern Plains, Lutherans in the Northern Plains, and Mormons in Wyoming, while still remaining generally the largest denomination in the region. In the 1990s Catholicism ranked first in number of adherents in the states of Montana (36.9 percent), Wyoming (27.5 percent), Colorado (37.3 percent), Nebraska (33.3 percent), and Kansas (27.3 percent); second in North Dakota (35.8 percent, behind Lutheranism), South Dakota (30.0 percent, behind Lutheranism), and Texas (32.8 percent, behind Baptists); and fifth in Oklahoma (6.8 percent, behind Baptists, Methodists, and various Pentecostal and Holiness groups). The religious landscape of the Plains is still filled with Catholic churches, schools, seminaries, hospitals, orphanages, and monasteries (of which there are four in both North and South Dakota).

In some parts of the Plains, especially areas of Latino in-migration, the number of Catholics is increasing. The diocese of Lubbock, Texas, for example, was established in 1983 in response to the growing population of adherents. But more generally in the region, the future for Catholicism is clouded. Since the 1960s the numbers of priests and nuns have declined significantly, and many now are aged. Few young men and women are replacing them. There are relatively few counties in the Plains where every congregation has a resident priest. In each of Pembina and Stutsman Counties, North Dakota, and Custer County, Nebraska, in 1990, for example, there were more than six congregations without resident priests. The trend suggests that, barring radical changes, such as allowing priests to marry or women to be ordained, the number of parishioners served by each priest is only going to increase as Roman Catholicism is stretched thin over much of the Plains.

See also EUROPEAN AMERICANS: Douglas, Thomas (Earl of Selkirk) / HISPANIC AMERICANS: San Sabá Mission and Presidio / LAW: North Dakota Anti-Garb Law / WAR: San Sabá Mission, Destruction of.

David J. Wishart University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Abramson, Harold J. Ethnic Diversity in Catholic America. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1973.

Gaustad, Edwin Scott, and Philip L. Barlow. New Historical Atlas of Religion in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Previous: Roberts, Oral | Contents | Next: Sanapia

XML: egp.rel.043.xml