DOUKOBORS

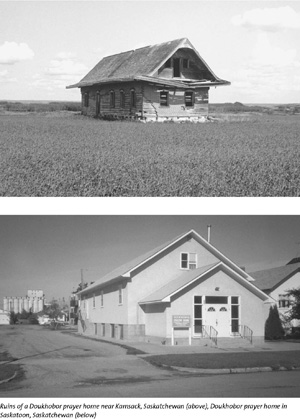

Ruins of a Doukhobor prayer home near Kamsack, Saskatchewan (above), Doukhobor prayer home in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (below)

View largerOriginating in seventeenth-century southern Russia, the Doukhobors (Spirit Wrestlers) were one of nearly 200 sects to break away from the Russian Orthodox Church. The Doukhobors renounced all human institutions, including church and government, and became pacifists.

Persecution in Russia and generous immigration policies framed by Clifford Sifton, Canada's minister of the interior, lured a constituent of 7,500 Doukhobors to Canada in 1899. The Canadian government agreed to their two stated requirements: that they be exempt from military service and that they be permitted to settle in solid blocks. They soon established fifty-seven successful farming communes in east-central Saskatchewan. Sifton wanted experienced farmers to settle the Great Plains, and the Doukhobors certainly qualified. For generations they had tilled the soil, and Leo Tolstoy called them "the best farmers in Russia."

In 1902, without warning, the Canadian government insisted that the Doukhobors individually register their settlement lands by swearing allegiance to the Crown, something the Doukhobor conscience would not allow. Reaction to the demand caused a three-way split among the Doukhobors. One group, composed of 236 families, complied and became known as Independent Doukhobors. They continue to farm in east-central Saskatchewan around the towns of Blaine Lake, Canora, and Kamsack. Another more zealous faction, known as the Sons of Freedom, determined to embarrass the government with a protest march, but the cold October weather drove them back home. The main group (the Community Doukhobors) sent for their leader from Russia, Peter the Lordly Verigin, and he led them to British Columbia, where previously owned lands were purchased that did not require the dreaded oath of allegiance.

The Doukhobor contribution to Plains agriculture cannot easily be exaggerated. By 1903 the community owned sixteen steam engines, eleven threshing machines, six flour mills, and five sawmills. They had amassed 600 horses, 400 oxen, and 865 cows. Just prior to their migration to British Columbia, they managed 258,880 acres of farmland, of which 49,429 acres had been seeded. The land was cultivated the hard way, with oxen, and sometimes even by hand. Although challenged by harsh winds, unpredictable water supplies, and the occasional prairie fire, the Doukhobors prevailed.

The fate of the British Columbia Doukhobors (the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood, or CCUB) bordered on the tragic. Peter Verigin was killed on October 24, 1924, when the train he was riding from Castlegar to Grand Forks, British Columbia, was hit by an explosion. In 1938, partially in fear of such a large utopian experiment, involving some 10,000 people with property worth $6 million, the Canadian government initiated a surprise foreclosure on the community. Doukhobor lands and properties were seized and sold at prices well below cost, and the ccub was liquidated.

Eager to keep their vision alive, the Doukhobors formed the Union of Spiritual Communities in Christ (USCC), which continues to sponsor a number of local and national events related to Doukhobor history, spirituality, and culture.

See also POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT: Sifton, Clifford.

John W. Friesen University of Calgary

Friesen, John W., and Michael M. Verigin. The Community Doukhobors: A People in Transition. Ottawa: Borealis Press, 1996.

Tarasoff, Koozma J. Plakun Trava: The Doukhobors. Grand Forks, British Columbia: Mir Publication Society, 1982.

Woodcock, George, and Ivan Avakumovic. The Doukhobors. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Ltd., 1977.

Previous: Distribution of Religions | Contents | Next: Eastern Orthodox

XML: egp.rel.018.xml