PROTEST AND DISSENT

Protest and dissent have helped shape the history of the Great Plains in the modern era. Dramatic episodes like the 1919 Winnipeg (Manitoba) General Strike and the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, are just a few of the many efforts that have made their impact felt in the region and beyond. On numerous occasions, individuals and groups have taken a public stand to denounce a perceived evil or promote a desired good. Sometimes protest was tied to a more permanent effort, such as the labor movement, a farmers' organization, or an ideological cause; other times, it was a single outburst of anger or complaint. Dissenting views also were advanced by the formation of local civil rights groups like Omaha's De Porres Club or radical newspapers like Kansas's Appeal to Reason, or even in letters written to the local press. Protest and dissent have not been isolated topics in the Great Plains; rather, they have been major elements in the region's history.

Farm Protest

Deputies with nightsticks line the highway coming into Omaha, Nebraska, to protect trucks against Farmers Holiday Association demonstrators, September 1, 1932.

View largerMuch of the protest has an economic origin. Hard-pressed farmers from Texas to Alberta have organized repeatedly in an effort to obtain better prices for their crops and livestock, fairer treatment from railroads and other corporations, and better community and public services. On a number of occasions, farm groups that first organized in the United States spread to Canada's Prairie Provinces. For example, in the late nineteenth century, the Patrons of Husbandry, or the Grange (formed in 1867), preached a gospel of education, economic cooperation, and social activity for the farm family. It met with great success initially when it launched a cooperative crusade in the 1870s. Although its strongest outposts were in the Midwest, the Grange also enjoyed a strong following in some Plains states and in the Prairie Provinces. Its experience was shared by numerous other farm organizations that emerged in the region in subsequent decades. In the early twentieth century, the American Society of Equity (organized in 1902) emerged as an influential transborder movement as well. It focused most of its energies on marketing and cooperatives, although it also lobbied politicians and sponsored social and educational programs. Ultimately, the Society of Equity on both sides of the forty-ninth parallel played a role in the emergence of the Nonpartisan League (NPL), an agrarian political movement that had its origins in North Dakota in 1915.

Time and time again, Great Plains farmers have organized to avoid the middleman, advance the interests of rural people, and preserve the family farm. They met with their greatest successes between 1910 and 1960. In the Prairie Provinces, the Grain Growers Associations, the United Farmers of Alberta (UFA), the United Farmers of Canada, Saskatchewan Section, and the United Farmers of Manitoba were the important farm groups that emerged prior to 1930. They promoted a gospel of farm cooperatives and agrarian politics. Among their greatest assets was The Western Producer, a newspaper that served a major educational and propaganda role for decades. South of the forty-ninth parallel, the comparable movement for American farmers, particularly from the World War I era into the 1950s, was the National Farmers Union (NFU). Cooperatives, education, and political activity were all part of the agenda of this effort, which had its greatest presence in the Plains states, particularly in North Dakota and Oklahoma. There were numerous parallels between the Canadian and American farm movements, one of which was the important role that women often played in sustaining these efforts, but the response to particular problems often differed from province to province and from state to state. For example, the oncenonpartisan ufa entered politics in 1922 and dominated the Alberta provincial government until 1935. In the United States, however, the NFU was never tempted to transform itself into a political organization.

The Great Depression of the 1930s presented an enormous challenge to existing farm groups in the Great Plains. Cooperative marketing was not a remedy for low farm prices, and farmers across the region were threatened with foreclosure and other economic disasters. Government at all levels in the United States and Canada was slow to respond to the unprecedented crisis. What emerged was a grassroots protest movement, or what some have coined the farm revolt of the 1930s. The major American organization was the Farmers Holiday Association, which sponsored farm strikes or withholding actions and interfered with forced farm sales through "penny auctions." The Farmers Holiday Association began in 1932 and spread across the Upper Midwest and Northern Plains. Hundreds and even thousands of farmers took part in demonstrations, penny auctions, and marches on state capitols. In February 1933 an estimated 4,000 farmers gathered on the steps of the new state capitol building in Lincoln, Nebraska, demanding a moratorium law.

But the first skirmishes of the farm revolt of the 1930s were fought by smaller groups. Communist-led organizations, the United Farmers League (UFL) and the Farmers Unity League (FUL), conducted penny auctions before the better-known Farmers Holiday Association came into existence. A Manitoba farm sale was halted by an FUL group in early 1931, and similar episodes soon took place on both sides of the border. For a short time it looked as if the countryside in the Great Plains was in revolt. Ultimately, federal farm programs helped undercut the appeal of agrarian insurgency in the United States. Yet the farm revolt of the 1930s dramatized the plight of American and Canadian farmers, pressured government to provide assistance, and played a role in reconfiguring the political culture of the region.

Farm protest in the more recent era has had less impact. During the 1950s and 1960s a new American farm group emerged, the National Farmers Organization (NFO). It focused its attention on marketing, ultimately opting for collective bargaining. Like the farmers' groups of the 1930s, NFO initially attracted widespread publicity. It, too, sponsored withholding actions or strikes but soon settled down, establishing a niche particularly among dairy and hog farmers. The National Farmers Union of Canada, largely a Saskatchewan group, developed a parallel course of action in more recent years as well. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, farmers again were faced with low prices and high debt and interest rates. A new farm revolt ensued on both sides of the border, and the older farm groups were often bypassed by the insurgency. The main vehicle of this protest in the United States was the American Agriculture Movement, which was formed in 1978. It was accompanied by many smaller groups in the next several years, most of which were organized in the early 1980s. A Canadian Agriculture Movement was formed, and an umbrella group, the North American Farm Alliance, emerged in 1982, open to both American and Canadian membership. The 1980s probably witnessed more farm protest than any time since the early 1930s. These efforts sometimes borrowed tactics and rhetoric from earlier eras; for example, Mary Elizabeth Lease's alleged comment from the late nineteenth century, "Farmers need to raise less corn and more hell," was often quoted with approval. Such efforts again drew attention to the plight of farmers, but there were significantly fewer of them than previously, so their political influence was correspondingly reduced as well. By the end of the twentieth century, the ranks of family farm organizations throughout the Plains fell far short of earlier days, when farm protest and farm votes determined elections on both sides of the border.

Yet the legacies of those earlier efforts are manifest in the region. Farm cooperatives to buy wheat and sell oil and gasoline dot the Plains from Texas to Alberta; North Dakota continues to operate a state-owned bank; Nebraska forbids nonfamily farm corporations from owning and operating farms; and the Canadian medicare system, first promoted by the farmer-dominated Cooperative Commonwealth Federation in Saskatchewan, remains in place.

Labor Protest

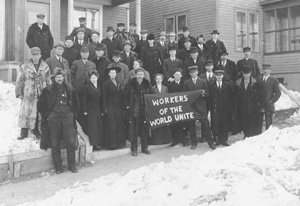

Socialist group at Minot, North Dakota, convention, 1910

View largerWorkers in the Great Plains often have protested because of their wages and working conditions. While the region generally has not had the reputation as a center of labor protest, organized labor has had an extended history in Winnipeg, Brandon (Manitoba), Edmonton, Calgary, Regina, Saskatoon, Omaha, and Kansas City, as well as in other railroad and mining centers. Craft unions organized skilled workers such as printers, carpenters, and bricklayers in the late nineteenth century in many communities in the Plains, and they, along with railroad unions, ranked among the most successful unionization efforts in that era. An important effort outside the craft unions was that of the Knights of Labor (organized in 1867), an attempt to organize workers regardless of skill, gender, or race. Although the Knights had their greatest success in the northeastern and midwestern United States, they also had a significant presence in the Plains states and parts of the Prairie Provinces. Winnipeg, Omaha, and Kansas City, Kansas, were among the strongest Knights of Labor communities in the region, and the Kansas City Knights emerged as a strong political force in the 1880s. Then, the Knights seemed a real alternative to the craft union approach. Ultimately, however, the "bread and butter" unionism of Samuel Gompers and the American Federation of Labor prevailed in the United States and in Canada as well.

However, in the early twentieth century a more militant form of unionism—often called industrial unionism because it sought to organize workers in particular industries regardless of job skill—had a strong presence in some cities and in the countryside. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was formed in 1905 and sought to organize all workers into one big union. More radical than craft unions, Wobblies (as IWW members were called) sought to replace the existing economic and political order with workers' rule. Although the iww tried to recruit members from all occupations, in the Great Plains this union met with its greatest success in the wheat fields, where it organized harvest hands. From 1915 to 1917 thousands of migratory workers from Oklahoma to North Dakota had red cards signifying iww membership. At one point, a tentative closed shop arrangement between the NPL in North Dakota and the iww was negotiated, only to be repudiated by the farm group's members soon after. Local authorities often suppressed the Wobblies, two noteworthy crackdowns occurring in Minot, North Dakota, and Mitchell, South Dakota. After the United States entered World War I in 1917, repression of radical groups became the norm, and the Wobblies were harassed repeatedly. During the war years and the anticommunist "Red Scare" that followed World War I, the iww was decimated in the Plains states.

The "one big union" idea also had appeal north of the forty-ninth parallel, as the iww established a foothold in western Canada prior to World War I. The war experience itself had a radicalizing effect on many Canadian workers, and western Canada experienced its greatest labor strife in history in 1919. Pent-up resentment, increased militancy, and the example of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia all served to encourage Canadian unionists to take the offensive after World War I. When the Western Labor Conference met in Calgary in March of 1919, militant labor sentiments were at fever pitch. The gathering denounced the capitalist economic order, extended greetings to the government of the Soviet Union, and opted to form a new union open to all workers, called the One Big Union (OBU). Like the IWW before it, the obu was a rejection not only of the existing economic order but also of the traditional labor movement led by conservative labor leaders like Samuel Gompers.

Growing labor strife across Canada coincided with the formation of the OBU. A showdown between employers and the new labor militancy occurred in Winnipeg in the summer of 1919. The famous Winnipeg General Strike has been portrayed as both a revolutionary upheaval and a repressive counterrevolution against legitimate trade union aspirations. As a practical matter, the labor troubles in Winnipeg did not grow out of a confrontation between the OBU and local employers. Rather, they were related to more conventional disputes over wages and the right of collective bargaining. When workers went out on strike, many other local unions walked out in sympathy with the strikers. Employers and politicians, however, portrayed the Winnipeg General Strike as the beginning of a revolution and seized every opportunity to suppress the strikers. General strikes in other western Canadian cities followed, as unionists sought to show their support for the Winnipeg strikers. Police, soldiers, employers, and returning veterans all joined in the fray in Winnipeg, and the strikers were routed after three weeks of struggle. This defeat marked the end of an era and a turning point in labor history in the Great Plains. Never again, north or south of the forty-ninth parallel, would there be such a confrontation between employers and workers.

The 1920s were labor's lean years in both the United States and Canada. Kansas miners, Nebraska and Kansas packinghouse workers, and railroad workers across the U.S. Plains all suffered defeat in the early 1920s, as did miners and others in the Prairie Provinces. One noteworthy episode in southeast Kansas involved female relatives of male coal miners. During the coal strike of 1921, these women organized the "Amazon Army," which toured mine sites, picketing and attacking strikebreakers. This strike ended in failure, as did miners' strikes in western Canada in this era.

Organized workers had little to celebrate anywhere in the Great Plains until the mid- to late 1930s, when the labor movement regrouped and launched new organizational drives during the Great Depression. This time, benefiting from new labor legislation and the example of union success elsewhere in the United States, workers organized new unions and flocked to old ones. One of the most important developments was the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which was a federation of industrial unions. Workers flocked to the new industrial unions on both sides of the border. (In both Canada and the United States, unions often are referred to as internationals, as they have affiliates in both countries.) Yet union growth was not limited to the new unions. Old craft unions, including the Teamsters, which emerged as a major union for the first time, also enjoyed important organizational successes. With the outbreak of World War II, union militancy was replaced by no-strike pledges, but union membership and political influence continued to grow. In Saskatchewan, a farmer-labor political coalition, the Cooperative Commonwealth Confederation (CCF), first came to power in 1944, and prolabor candidates were elected to ridings in numerous assembly districts there and in Manitoba. South of the border, however, a conservative reaction to labor gains ensued in the war years and the immediate postwar period.

On earlier occasions, anti-union sentiment had resulted in employer counteroffensives known as the open shop movement. The movement had been particularly strong in Omaha and Fargo; the Omaha Business Men's Association asserted that "Omaha is the best open shop city of its size in the United States." Such efforts had been swept away by the late 1930s in the wake of union successes, but employers regrouped following World War II and launched a major effort to revive the open shop. In the Dakotas and Nebraska, they successfully promoted "right-to-work" laws. Both South Dakota and Nebraska amended their constitutions to prohibit the union shop in 1946, and more than a decade later Kansas passed a right-to-work measure as well. These anti-union efforts amounted to a businessmen's protest movement.

Labor membership in Plains states lagged behind that in more industrialized states, but the labor movement continued to represent tens of thousands of workers. Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, as teachers and other public employees opted for unionization across the country, Plains states passed measures providing for collective bargaining, particularly for teachers. One noteworthy episode occurred in South Dakota, when Rapid City teachers went out on strike in 1970. Today, university and college professors in the Prairie Provinces, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas are among public employees exercising their right to bargain for wages and working conditions.

Political Protest and Dissent

Political protest and dissent has been an integral feature of the political culture of the Plains states and Prairie Provinces. Aside from the Populist movement of the 1890s, third parties in the Plains states have been more a vehicle for protest and advocacy than a means of assuming political power. In the Prairie Provinces, on the other hand, third parties such as Social Credit and the CCF (and its successor, the New Democratic Party) have met with much greater electoral success in the twentieth century. There, too, however, minor third parties, including the Communist Party, have played a similar protest role. Socialists often ran for office in the early twentieth century, but their campaigns proved to be more protest than a means of gaining public office. The exception was Oklahoma, where members of the Socialist Party were elected to five state legislatives seats and to more than 100 local offices in 1914.

A key element in the pre-World War I Socialist effort was a highly successful weekly newspaper, Appeal to Reason, published in Girard, Kansas, by Julius Wayland. Folksy, well-written, and controversial, Appeal to Reason may have had the largest circulation of any political paper in the United States (more than 760,000 of some issues), and subscribers across the country read this paper for years. (Upton Sinclair's novel The Jungle first appeared in serial form in the Appeal to Reason.)

Itinerant speakers also played a major role in promoting the Socialist cause in the U.S. Plains, and Kate Richards O'Hare was among the best known. She spoke at Socialist encampments in Oklahoma and at other party gatherings across the region. During World War I she was convicted of violating the Espionage Act for antiwar comments she allegedly made in a speech in Bowman, North Dakota.

In the U.S. Great Plains, farmers and smalltown folk were more likely than city folk to be Socialists. Beatrice, Nebraska, Sisseton, South Dakota, and Minot, North Dakota, were among the communities that elected Socialist mayors. The emergence of third parties as a kind of protest was behind the more successful npl that dominated North Dakota politics and took over courthouses in portions of eastern South Dakota and northeastern Montana from 1916 to 1922.

Other third-party political protest involved Communists in the early 1920s and after. Though there never were many Communists in the U.S. Plains, small pockets existed in Finnish settlements in the Dakotas and Montana and in a number of other communities across the Northern Plains at different times. Key Communist leaders Earl Browder and James Cannon both came from Kansas and underwent their baptism of fire in radical causes there. (Cannon subsequently broke with the Communists and served as the chief leader of the American Trotskyist movement until his death.) Ella Reeve "Mother" Bloor was the most prominent Communist figure in the region during the Great Depression. An energetic agitator despite her age, the sixty-sevenyear- old Bloor played a key role in the farm revolt of that era, traveling across the Dakotas, Montana, and Nebraska from 1930 to 1934, speaking and organizing wherever she went. While most of her efforts involved farmers, she was arrested in Nebraska for her role in the 1934 Loup City Riot in which Communists and their allies tried to organize women in a local chicken-processing plant. She ultimately served thirty days in jail.

Communists also played a role in the labor and unemployment struggles of the 1930s. They likely had a stronger presence in the Prairie Provinces than in the U.S. Plains states. Communists had a following in some mining districts, Ukrainian settlements, and Winnipeg's North End. In 1935 they played a key part in the unemployment march across western Canada that was halted dramatically with the Regina Riot. Marchers had trekked to Regina en route to their ultimate destination, Ottawa, where they planned to petition the federal government for relief. At Regina, however, local authorities and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police intercepted the trekkers, attacking a mass meeting and brutally dispersing them.

Communists participated in the larger farm and labor organizations in the region. Their strongest base after the 1930s probably was in Winnipeg and smaller Ukrainian communities. As late as the 1960s, a Communist represented the North End in the Winnipeg City Council. Some Communists had participated in the CCF in Saskatchewan and the NFU in the Northern Plains states at times. Yet their role should not be exaggerated. Opponents often used the "red" issue as a way of discrediting liberal causes, and the NPL, CCF, and NFU all were subjected to such attacks. Many liberal groups in this region often found themselves the target of right-wing protest groups.

Political protest and dissent have not been a left-of-center monopoly. An important early right-wing protest group in the Plains states and Prairie Provinces was the Ku Klux Klan. It quickly attracted a strong following, particularly in Oklahoma, but had a presence throughout the entire region in the 1920s. Governors in both Oklahoma and Kansas went to war with the Klan, though Oklahoma governor John C. "Our Jack" Walton's primary motivation in doing so was to avoid impeachment and removal from office. (This effort failed, as his bizarre and arbitrary behavior alienated many of his former supporters.) The Klan spread to Canada in the mid-1920s and attracted a strong following in both Alberta and Saskatchewan. There, its drawing power came from its anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant stance. Recent historians of the Klan increasingly stress the complexity of this topic, observing that its adherents often were motivated more by a desire to preserve existing moral codes than by racism and anti-Catholicism. While scholars disagree on the significance of the Klan in this era, there seems little question that Protestant clergymen often promoted its cause on both sides of the border.

Right-wing protest probably has come in as many varieties as its counterparts on the left. In the 1930s, coinciding with President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal (and sometimes in response to it), an articulate right-wing protest element emerged in the Plains. Key figures in this grouping included Gerald B. Winrod and Elmer J. Garner, both then from Wichita. Winrod published the Defender magazine, and Garner edited Publicity, a newspaper. By the late 1930s both of them identified the New Deal with Jews and communists. Anti-Semitic and isolationist, they saw the Roosevelt administration dominated by Jews and vehemently denounced U.S. foreign policy. Following Pearl Harbor, however, both tempered their remarks. Still, in 1942 they were indicted for sedition, along with twenty-nine other right-wing figures. Garner died two weeks after the trial began, and the case against Winrod and other defendants ended in a mistrial in 1946. Some historians maintain that this prosecution was an overreaction to the right wing, a kind of "brown scare," analogous to the overreaction to the left, or "red scare," of the post–World War II era.

Support for Sen. Joseph McCarthy emerged in the Plains states during the cold war years. While there was no McCarthyite movement per se, McCarthyite attacks were made against many groups and people. For example, in northeast Montana, a Farmers Anti-Communist Club appeared and ran advertisements in two local weekly newspapers in the mid-1950s. The chief target of this group apparently was the NFU, and the advertisements often portrayed the liberal farm group as a Communist front or an organization in which Communists played a major role. Later, in the 1960s, the John Birch Society appeared in the region. Its national leader denounced Dwight Eisenhower's presidency as too liberal, sometimes suggesting that the popular president had been a tool of the Communists. Birch Society members probably had their greatest influence at the local level, particularly on school boards.

An even more extreme right-wing protest movement emerged in the 1980s and 1990s. At the depths of the farm crisis of the 1980s, the Posse Comitatus and other extremist groups recruited among hard-pressed farmers. Built on a racist and anti-Semitic ideology, this movement preached a harsh, antigovernment gospel that justified violence and fraudulent financial practices. Numerous publications, speakers, and workshops promoted this message. While observers differed in their assessment of the recruitment success of these groups, all agreed that the groups built a following in the countryside. Gordon Kahl of North Dakota and Arthur Kirk of Nebraska were two of their recruits. Both men resisted arrest and died in shootouts with authorities, becoming martyrs to their extremist causes.

The Posse Comitatus has faded from view while continuing as an intermittently active arm of antigovernment protest. Its torch has been picked up by newer organizations, including some militia groups. In Garfield County in northeastern Montana, a group calling themselves the Freemen claimed they had established sovereignty in Justus Township and constructed a stockade around their farm in 1996. They financed their actions by passing millions of dollars' worth of bad checks. A long siege of more than two months ensued before the group surrendered to the authorities, who included a large number of FBI agents. A similar episode occurred in West Texas in 1997. In Jeff Davis County, a rightwing group claimed they had reestablished the Republic of Texas, arguing that the United States' annexation of Texas in 1846 had been invalid. Also heavily armed, this faction subscribed to many of the political ideas of the Posse Comitatus and threatened to shoot anyone who interfered with their activities. After the kidnapping of a local couple, authorities acted and suppressed the would-be secessionist group. Its leaders were sentenced to long prison sentences for kidnapping and passing millions of dollars' worth of bad checks.

Unlike earlier protesters, these contemporary right-wing extremist groups do not seek to change government policy; instead, they want to form their own kind of government outside existing political institutions. In the wake of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, the media and others have focused much more attention on right-wing protest groups who preach violence and vigilante-type justice. Once simply characterized as tax protestors, they now are subject to greater scrutiny and concern.

Civil Rights and Ethnic Protest

An early protest involving Native Americans was that of Thomas H. Tibbles and Standing Bear. In 1879 the U.S. government ordered Gen. George Crook to return Standing Bear and his Ponca band from their traditional homeland in northeastern Nebraska to Indian Territory, where they had been removed two years previously. Crook, appalled by the assignment, notified Tibbles, a reporter for the Omaha Daily Herald, who used the story to focus attention on citizenship rights for Native Americans. Tibbles also arranged for two local attorneys to file a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of the Ponca leader in federal court. The judge ruled that Standing Bear and his followers were U.S. citizens who had withdrawn from the Ponca tribe, and that the federal government had no basis to order their return to Indian Territory. Following the trial, Crook and Tibbles continued to aid the Ponca cause to regain their land in northeast Nebraska. Susette La Flesche, the daughter of an Omaha chief, joined the effort, later marrying Tibbles. She devoted much of her life to working for Indian rights, including the recognition of their U.S. citizenship.

African Americans often were treated as second-class citizens in the Plains. After World War I there were several violent outbreaks against African Americans, including a 1919 lynching in Omaha and the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot that resulted in the deaths of at least thirty-nine African Americans, and probably many more. Some African Americans organized chapters of the National Association of Colored People (NAACP), while others formed units of Marcus Garvey's back-to-Africa group, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). By the mid-1920s Oklahoma City and Omaha had both NAACP and UNIA affiliates, Topeka and Lincoln had NAACP chapters, and Kansas City and Tulsa had UNIA divisions.

Civil rights activism had a long history in the region. Plains blacks protested the film Birth of a Nation as racist and sought to eliminate discrimination in employment and education. The U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 landmark decision in Brown v. The Board of Education, which paved the way for desegregation of the public schools, was the result of several naacp lawsuits, including one on behalf of Linda Brown and other black students in Topeka, Kansas. Some African Americans in the Great Plains opted for direct action even before the outbreak of activism in the South in the 1960s. Omaha's De Porres Club, organized in 1947, integrated a Catholic parish and pressured the local Coca Cola bottling works (located in the city's largest black neighborhood) and the transit company to hire blacks. For a time, this group was affiliated with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). In 1958 NAACP youth groups in Wichita and Oklahoma City conducted successful lunch-counter sit-ins in order to obtain service for blacks.

One of the region's most dramatic protests was the 1973 takeover of Wounded Knee. The American Indian Movement (AIM) launched a frontal assault on both discrimination against Native Americans and the existing power structure on reservations. In early 1973 AIM took control of the community of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, which was the site of the 1890 massacre of more than 200 Sioux men, women, and children by the U.S. Seventh Cavalry. While AIM sought to dramatize the plight of contemporary Indians, the takeover also was aimed at overthrowing the current tribal leadership on the Pine Ridge Reservation. The occupation lasted seventy-one days. Although AIM was not successful in achieving its stated objectives, this episode heightened media attention on the problems faced by Indians in the region. Canadian Indians supported the South Dakota occupation, and the Ojibwa Warrior Society briefly took over a site across the Manitoba line in western Ontario later the same year. Native American protest on both sides of the forty-ninth parallel became commonplace in the late twentieth century.

Ubiquity of Protest

Protesting against animal activists in South Dakota

View largerNot all dissent involves political causes. One noteworthy example of quiet dissent that still resulted in serious controversy was an effort to provide cooperative medical care in the small southwestern Oklahoma town of Elk City. A Lebanese immigrant, Michael Shadid, settled in this community in 1911 after graduating from medical school. Determined to provide access to adequate health care, he and the local Farmers Union raised funds to establish a cooperative hospital. Although boycotted and opposed by the local medical establishment, the Elk City facility persisted and provided excellent and inexpensive health care to the community for a generation. Ultimately, in 1964, it became a local community hospital, no longer based on cooperative principles.

A different kind of dissent regarding medical services emerged in Saskatchewan, when the ccf government established medicare in 1962. There, doctors went out on strike, opposing what they saw as socialized medicine. A "Keep Our Doctors Committee" appeared even before the walkout, and most of the hospitals in the province were closed. The strike itself lasted less than a month, but ultimately the medical establishment across Canada became reconciled to publicly funded, universal medical care.

The themes of protest and dissent are also present in the cultural history of the region. One of the most significant examples is the 1978 film Northern Lights, which tells the story of an NPL organizer in northwestern North Dakota in 1915–16. Directed by John Hanson and Rob Nilsson, this black-and-white film featured mostly local people in its cast and premiered in the small town of Crosby, North Dakota. It won an award at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival. The film was narrated by Henry Martinson, then in his nineties and poet laureate of North Dakota, who was a veteran of numerous social and political causes dating back to his involvement with the Socialist Party and the NPL of the World War I era.

Perhaps the best-known artist of the Great Plains to emerge out of a protest tradition was songwriter-folksinger Woody Guthrie of Oklahoma. Among his numerous songs and ballads were "Talkin' Dust Bowl Blues" and "This Land Is Your Land." Guthrie met with his greatest success on the East Coast, where he performed and recorded songs. His work was an influence on a number of other singers, including his friend Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, and Bruce Springsteen. Agnes "Sis" Cunningham was another Oklahoma protest singer who emerged in the 1930s. She participated in a left-wing theater troupe known as the Red Dust Players and helped organize cio unions in her home state. Later, in the 1940s, she joined Guthrie in New York City as a member of the well-known Almanac Singers.

The literature of the Great Plains also contains dissenting themes. Marie Sandoz's Capitol City, while not one of her strongest works, reveals the author's estrangement from the dominant culture and her sympathies with the underdog, including embattled farmers, worried by foreclosures, and striking Teamsters in the 1930s. Another regional protest novel is William Cunningham's Green Corn Rebellion. (Cunningham was the older brother of Sis Cunningham). This work, published in 1935, is an example of the proletariat novel that appeared in the 1930s. It treats a rural Oklahoma uprising that was quickly suppressed by local authorities in the wake of the U.S. entry into World War I.

Nonfiction works treating Great Plains topics reflect regional dissenting themes as well. Bruce Nelson's Land of the Dacotahs, first published in 1946, offers an episodic history of the Dakotas and Montana. It sides with Indians, homesteaders, and North Dakota's NPL. Unlike Nelson, who was from Minnesota, Angie Debo lived almost all of her ninety-eight years in the Great Plains. Trained at the Universities of Oklahoma and Chicago, she is recognized as one of the leading authorities on the history of Southern Plains Indians. Her most important work may have been And Still the Waters Run, a historical treatment of how white Oklahomans stole large amounts of Indian land. A number of the culprits were still alive and were prominent citizens at the time Debo wrote the manuscript, and the University of Oklahoma administration refused to allow its press to publish the book. Finally, And Still the Waters Run was published in 1940 by Princeton University Press. Debo's work was characterized by a strong sympathy toward Indians at a time when that stance was unpopular in Oklahoma.

Critical treatments of the Great Plains sometimes themselves provoked protest. Local responses to Pere Lorentz's 1936 film documentary, The Plow That Broke the Plains, and John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath constituted yet another variety of regional protest. Lorentz's classic twenty-eight-minute film provoked a firestorm of journalistic and political criticism for defaming South Dakota, even though none of its footage was shot in that state. Likewise, The Grapes of Wrath was perceived as a libel on Oklahoma by some local editorial writers, especially in Oklahoma City.

Conclusion

Protest and dissent permeate the recent history of the Great Plains. In some cases, especially in regard to farm and labor protest, they constitute an important part of the background of new organizations and institutions. On other occasions, protestors and dissenters have had little lasting effect; their voices were raised or their remarks recorded, and then they faded into obscurity, only to be rediscovered later (if at all) by enterprising journalists or historians. New causes have appeared in recent decades, but they often utilize tactics introduced long ago. In the 1980s and 1990s, for example, protestors on both sides of the abortion issue picketed and sometimes resorted to civil disobedience, following courses of action earlier laid out by the labor and civil rights movements. Historically, many people on numerous occasions have demonstrated their approval or opposition to current practices or proposed changes. The frequency and the geographic extent of their efforts demonstrate that protest and dissent have not been an aberration in the Great Plains; rather, they constitute an irreducible element of the region.

See also AFRICAN AMERICANS: Civil Rights; Omaha Race Riot; Tulsa Race Riot / AGRICULTURE: Corporate Farming / FILM: The Grapes of Wrath ; Northern Lights ; The Plow That Broke the Plains / LAW: Anti-Corporate Farming Law; Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka / LITERARY TRADITIONS: Debo, Angie; Sandoz, Mari / MEDIA: Western Producer / MUSIC: Guthrie, Woody / POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT: Cooperative Commonwealth Federation; New Democratic Party; Populists (People's Party).

William C. Pratt University of Nebraska at Omaha

Barthelme, Marion K. Women in the Texas Populist Movement: Letters to the Southern Mercury. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1997.

Bumsted, J. M. "1919: The Winnipeg Strike Reconsidered." The Beaver (June– July 1994): 27–44.

Corcoran, James. Bitter Harvest: Gordon Kahl and the Posse Comitatus: Murder in the Heartland. New York: Penguin Books, 1990.

Dyson, Lowell K. Red Harvest: The Communist Party and American Farmers. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982.

Green, James R. Grass-Roots Socialism: Radical Movements in the Southwest, 1895–1943. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.

Haug, Charles James. "The Industrial Workers of the World in North Dakota, 1913–1917." North Dakota Quarterly 39 (1971): 85–102.

Henson, Tom M. "Ku Klux Klan in Western Canada." Alberta History 25 (1977): 1–8.

Joyce, David D. An Oklahoma I Had Never Seen Before: Alternative Views of Oklahoma History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.

MacPherson, Ian. "Selective Borrowings: The American Impact upon the Prairie Co-operative Movement, 1920–39." Canadian Review of American Studies 10 (1979): 137–51.

McCormack, A. Ross. Reformers, Rebels, and Revolutionaries: The Western Canadian Radical Movement 1899–1919. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

Monod, David. "The Agrarian Struggle: Rural Communism in Alberta and Saskatchewan, 1926–1935." Historie sociale/Social History 35 (1985): 98– 118.

Pratt, William C. "Workers, Bosses, and Historians on the Northern Plains." Great Plains Quarterly 16 (1996): 229–50.

Saloutos, Theodore, and John D. Hicks. Twentieth- Century Populism: Agricultural Discontent in the Middle West, 1900–1939. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1964.

Sharp, Paul F. The Agrarian Revolt in Western Canada: A Survey Showing American Parallels. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1948.

Shover, L. John. Cornbelt Rebellion: The Farmers' Holiday Association. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1965.

Wilson, L. J. "Educational Role of the United Farm Women of Alberta." Alberta History 25 (1977): 28–36.

Previous: | Contents | Next: Aberhart, William

XML: egp.pd.001.xml