WICHITAS

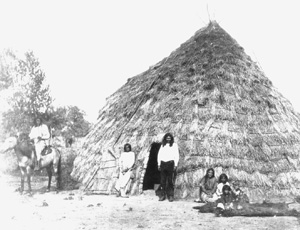

Wichita Indian grass house

View largerWhen the Spanish explorer Coronado traveled across the Southern Plains in 1541 in search of the fabled riches of Quivira, he encountered large villages of a distinctive tattooed people along the Great Bend of the Arkansas River, near present-day Arkansas City, Kansas. This was the initial European contact with the Native Americans now recognized as the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes.

Early historic accounts from Coronado's entrada and the later Oñate expedition found the Wichitas referring to themselves as the Quicasquiris or Quirasquiris (or Ki‘dikir' eis, based on interviews conducted with tribal members in 1949). Close study of Spanish and French explorers' visits with the Wichitas reveals a loosely aligned confederacy of a number of bands. These included the Taovayas, Tawakonis, Iscanis-Wacos, and the Wichitas proper. By the eighteenth century the Kitsais, another tribe related to the Wichita subgroups, had been assimilated by the Wichitas.

Linguistically, the Wichita language belongs to the Caddoan language family that also includes the Pawnee, Kitsai, Caddo, and Arikara languages. Historically, Wichita is most closely related to the Northern Caddoan subfamily languages of Kitsai and Pawnee and is more distantly related to Caddo of Proto-Caddoan derivation.

While many Native groups traditionally recognized as Plains societies (for example, the Cheyennes) have a relatively recent history in the Southern Plains, the Wichitas have been there for 2,000 to 2,500 years. They were among a diffuse group of people, possibly from Louisiana or Mississippi, who began a westward movement some 3,000 years ago. This migration gradually extended across the Plains, displacing existing residents. During this expansion, the newcomers began to develop regional distinctions in material culture, means of subsistence, and social, political, and religious organization. Archeologists now link these regional expressions to the historic Caddo, Kitsai, Wichita, Pawnee, and Arikara tribes. Archeological evidence and historic accounts reveal that the Wichitas ranged over much of the Southern Plains, including what is currently northcentral Texas, Oklahoma, and south-central Kansas.

Wichita subsistence practices reflected a dual economy based on farming and hunting. During the spring and summer they cultivated sizable plots of corn, beans, and squash and harvested wild plants such as amaranth and sunflower. Bison, deer, and small game were hunted. In the fall and winter the Wichitas conducted large-scale communal bison hunts. Greater reliance on hunting by a traditionally agricultural people was probably connected to the introduction of the horse in the seventeenth century.

The Aboriginal material culture of the Wichitas closely parallels that of other Plains village societies. A variety of natural products, such as animal bones and hides, wood, plant fiber, stone, and clay, were used in the manufacture of domestic goods, clothing, and ornaments. Much of the traditional technology was abandoned by the late nineteenth century in favor of European American goods. The most distinctive aspect of the Wichita material world was their beehive-shaped grass houses. These houses ranged from fifteen to thirty feet in diameter and twelve to twenty feet in height. The dwelling, consisting of fourteen to sixteen cedar posts with a frame of smaller cedar and willow poles, was covered with bundles of coarse grass. Four small poles extended about three feet from the peak of the house, representing the four world quarters or gods. Wichita dwellings were designed to house extended family units of roughly eight to ten people. Villages had from thirty to several hundred such residences. Wichita settlements in the eighteenth century also typically contained a palisade or fortification, although not all the houses of the village would be within this protected area.

Wichita society has been generally viewed as highly egalitarian, with male status acquired through individual achievements in hunting and warfare. However, there are indications that some Wichita subgroups, such as the Tawakonis, had chiefs or rulers with greater authority; inheritance of these positions appears likely to have occurred in some instances. A typical Wichita village would have a principal chief elected by the head warriors, a leader responsible for finding new village locations, shamans or medicine men, warriors, elders, and "no-count men," who were servants to the chief, leader, or priests. Women of the village were responsible for planting and tending the crops as well as most of the labor-intensive tasks, such as building houses, collecting firewood, and hauling water. Men were principally involved in hunting and warfare. As was the case in many Native American farming societies, kinship was matrilinear, or traced through the woman's side, and matrilocal, meaning that the husband moved to the residence of the wife's family after marriage.

The Wichitas recognized a host of sacred figures. These were divided into the gods and goddesses of the earth and sky. Supreme among these was the god known as Kinnikasus (Man Never Known On Earth), who was responsible for the creation of the universe and its parts. Other male gods controlled the heavens (with the exception of the moon goddess), whereas goddesses—the goddess of water, for example— reigned on earth. The Wichitas also believed that all animate and inanimate objects possessed a spirit and that everything could assume more than its apparent natural characteristics. These concepts played a significant role in the development of supernatural powers among the medicine men. The Wichitas have also been credited with establishing the calumet ceremony as a means of initiating truce conditions among Plains societies.

The arrival of Europeans on the Southern Plains dramatically transformed Plains tribes. The presence of the horse and European goods, weapons, and diseases brought about drastic changes in demographics, subsistence economies, and political structures of most tribes, including the Wichitas. The French and Spanish also manipulated the tribes, pitting them against each other in an effort to gain control of the Southern Plains. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Wichitas had continuous conflicts with the Apaches and Comanches to the west and the Osages to the east. By the mid-eighteenth century, they had established peace with the Comanches. Conflicts continued with the Apaches and Osages. In the 1750s the Osages forced the Wichitas from the Great Bend of the Arkansas River to the middle reaches of the Red River. The Wichitas maintained good relations with the French but never fully embraced Spanish authority. They won a major victory over the Spanish in 1759 when Col. Diego Ortiz Parilla failed in his attack on a Wichita village on the Red River.

The Wichitas may have had a total population of around 10,000 in the 1700s. Subsequently, introduced diseases and continuing conflicts with whites and other Indians led to significant population decline. By the late eighteenth century their population had dropped to about 4,000, and by the 1890s only 153 Wichitas remained.

In 1872 the Wichitas ceded all claims to their ancestral lands in Texas and Indian Territory to the United States and were left with a 743,000- acre reservation in present-day Caddo County, Oklahoma. However, this agreement was never ratified, and their title to the land remained in doubt. In 1901 the reservation was allotted and greatly reduced by the sale of "surplus lands."

The Wichita and Affiliated Tribes currently reside adjacent to the Anadarko Agency just north of Anadarko, Oklahoma. They hold some 1,260 acres of land in common trust with the Caddo and Delaware tribes. In 1995 there were 1,798 Wichitas, most of whom lived in Oklahoma.

Robert L. Brooks

University of OklahomaDorsey, George A. The Mythology of the Wichita. Washington DC: Carnegie Institution, 1904.

John, Elizabeth A. H. Storms Brewed in Other Men's Worlds. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1975.

Newcomb, W. W. Jr. The Indians of Texas. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1961.

XML: egp.na.127.xml