TREATIES

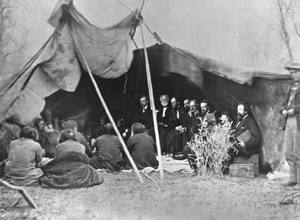

U.S. Army commissioners in council with chiefs, Fort Laramie, Wyoming, 1868

View largerIn both the United States and Canada, negotiated treaties were the instrument for obtaining Indian lands and more generally for extending federal control over Native peoples, while at the same time recognizing the sovereignty they retained. In the United States, the Constitution gave the executive branch the authority to negotiate treaties and the Senate the authority to ratify them. Treaty making was abolished in 1871, but similar bilateral agreements between the federal government and the tribes continued thereafter. In Canada, the provision for a treaty process was established with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, whereby the Crown reserved the sole right to purchase Indian lands. That authority was continued through the British North America Act of 1867, which passed on the Crown's authority over First Peoples to the new Dominion of Canada.

In both Canada and the United States, early treaties proclaimed peace and friendship between the government and the Native peoples. The fact is, neither of the colonizing powers had the military power to defeat the Indians, and treaties were a pragmatic alternative. After 1812, however, the population balance swung in favor of the European Americans, and treaties became the means to acquire Indian lands. Especially in the United States, it was a buyer's market. Pressured by settlers and mired in poverty, Indians rarely had any option but to sell. In many cases, consent to treaties was obtained only through fraud and duress. The surrender of the Black Hills by the Lakotas (Sioux) in 1877 and the sale of the Red River Valley of the North by the Red Lake and Pembina bands of the Chippewas are notable examples of such manipulation.

In the American Great Plains, treaty making for the purpose of obtaining Indian lands began with the cession of what is now southern Oklahoma by the Quapaw in 1818. This land, and vast areas subsequently obtained in the 1820s and 1830s in present-day Oklahoma, Kansas, and southern Nebraska, were bought from Plains Indians to make room for relocated Indians from the eastern United States. The next wave of treaties came in eastern Nebraska and southeastern Dakota Territory in the second half of the 1850s when the Pawnees, Omahas, Poncas, Otoe-Missourias, and Yanktons sold their ancestral lands, retaining only small reservations. European Americans moved in to settle the newly acquired public domain. This process was repeated westward and northward throughout the Great Plains in the following four decades. Indian dispossession, achieved through treaties, was the prerequisite for frontier settlement.

In Canada, the clearing of Indian title to the Prairie Provinces was done more quickly. From 1871 to 1877, in a series of seven numbered treaties, the many bands of Crees, Chippewas, Assiniboines, and Blackfoot relinquished their claims to the land and settled on reserves. The terms of each treaty varied only in detail. Through Treaties 1 and 2, for example, concluded in 1871, the Swampy Crees and Chippewas ceded 52,400 square miles of southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan in return for a reserve, a school, farm implements, a onetime payment of $3 per person, and an annuity of $3 per person.

Similar types of compensation were given south of the forty-ninth parallel. In both countries, payments for lands.the monies due the Indians.were used to fund the government's "civilization" programs, which aimed to assimilate the Indians as independent, selfsu. cient, Christianized farmers. But payments for Indian lands were so low (they averaged ten cents an acre in the Central and Northern Great Plains) and the quality of services and goods so poor, that the end product of treaty making was poverty, not self-sufficiency.

On the one hand, then, treaties can be viewed as a subterfuge, a means of acquiring Indian lands legally and without the more expensive and disruptive warfare. Negotiations took place, the Indians had their say, and the federal governments set the conditions of the divestiture. On the other hand, treaties established reservations and reserves where tribal law and government still prevail despite challenges. Treaties are not merely historical documents; they are contracts between sovereign powers, the foundation of Indian law, and often the legal justification for claims cases.

David J. Wishart

University of Nebraska-LincolnCohen, Felix S. Handbook of Federal Indian Law. Buffalo: William S. Hein Co., 1988: 33-67.

McQuillan, Aidan D. "Creation of Indian Reserves on the Canadian Prairies, 1870-1885." Geographical Review 70 (1980): 219-36.

Wilkinson, Charles F. American Indians, Time, and the Law. New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 1987.

XML: egp.na.118.xml