WOMEN HOMESTEADERS

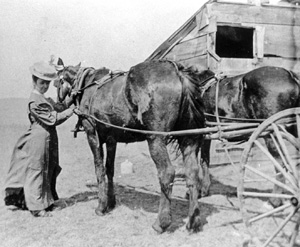

Agnes Lamb on the day she filed on her homestead land near the town of Washburn, North Dakota, ca. 1906

View largerThousands of women took advantage of the Homestead Act (1862) that offered free land in the American Great Plains. Women who were single, widowed, divorced, or deserted were eligible to acquire 160 acres of federal land in their own name. The law discriminated against women who were married. A married woman was not allowed to take land in her own name unless she was considered the head of the household. The majority of homesteading women were young (at least twenty-one), single, and interested in adventure and the possibility of economic gain.

Lucy Goldthorpe told how she got caught up in the excitement of the times. "Even if you hadn't inherited a bit of restlessness and a pioneering spirit . . . it would have been difficult to ward off the excitement of the boom." Pauline Shoemaker remarked, "I've done everything else, I might as well try homesteading." Louise Karlson was looking for a good investment: "When in 1908 I heard about the homestead land one could get . . . I thought, here is my chance." A few women homesteaded land to help a male relative expand his acreage. This was the exception rather than the rule, and even in these cases the women usually received some compensation for their efforts.

Homesteading provided widows with an economic opportunity often denied them elsewhere. Many had children to support. Tyra Schanke, when widowed, was left with three children, ages three, four, and five. Kari Skredsvig brought up her seven children on a homestead near Bowbells, North Dakota. Even the elderly women took part in this venture. Anna Hensel was sixty-seven when she immigrated to the United States from Bessarabia in southern Russia. A year later, in 1903, she declared her intent to become a citizen and applied for a homestead in Hettinger County, North Dakota. Women from almost all ethnic groups took advantage of homesteading opportunities. An extensive but not all-inclusive list would include Anglo-Americans, Norwegians, Swedes, Danes, Finns, Hollanders, Icelanders, Germans, Germans from Russia, Bohemians, Poles, Ukrainians, Lebanese, Irish, English, Scottish, Italian, African Americans, and Jewish Americans.

Although the initial experiences of homesteaders varied considerably, few women or men struck out on such an undertaking by themselves. Settlers usually came with family or friends, but a few managed alone. Kirsten Knudsen left Norway with two other young women, but she came to Mountrail County, North Dakota, by herself. She knew no one and could not speak English. She carried only a letter of introduction to an attorney from a mutual friend.

The length of time it took to "prove up," or receive title to the land, varied over the years. The Homestead Act of 1862 required a five-year residence, but the definition of residence was ambiguous. Some homesteaders left their land for lengthy periods of time to earn money, visit family, or escape severe weather. Others remained on the land most of the time. Shortly after the initial Homestead Act was passed, amendments provided for other ways of "commuting" the claim. One such option allowed the homesteader to reside on the claim for only fourteen months and then pay $1.25 an acre to receive title.

Women who took homesteads tended to "work out" as well. Many of them pursued careers as teachers, nurses, seamstresses, and domestic workers, but a few followed less traditional paths such as journalism or photography. Many eventually married, but some remained single. Those who achieved economic success used their resources in a variety of ways. Some stayed on their homestead and accumulated additional land. Others sold their holdings and invested elsewhere. In some cases homesteaders rented out the land and used the proceeds for personal or family needs. Ida Popp sold her land in Bowman County, North Dakota, and bought land adjoining her husband's claim. Lucy Gorecki traded her 160 acres for a commercial building in Fordville, North Dakota. Anna Mathilda Berg traded her homestead for a boardinghouse in Warwick, North Dakota.

In many ways, women who homesteaded resemble contemporary women. Their schedules were demanding, requiring flexibility, ingenuity, and endurance. Most would be considered community movers and shakers, as their initiatives were instrumental in building schools, churches, and other community institutions.

The homesteading period of history usually brings to mind stories of blizzards, prairie fires, and other catastrophic events. Yet tragedy is but one dimension of human life. To dwell on that aspect is to distort reality. In spite of their heavy demands, many homesteaders found time to devote to music, art, literature, and even poetry. A sense of humor was important in shaping their outlook on life.

Visitors to the homestead of Kirsten Knudsen likely were amazed to hear musical strains from the scores of operas such as La Traviata and Aida come floating through the prairie air. When Kirsten arrived on her homestead she brought with her the operas, memorized when she had spent time as a chorus girl in the National Theater in Oslo, Norway. Women as well as men were proficient in violin, piano, organ, and other instruments. Anna Zimmerman told of playing for dances with her brother. They both played accordion, violin, and guitar. Anna often played the harmonica and danced at the same time. Homesteading was more than tears and suffering.

A closer look at the lives of women who homesteaded does not reaffirm the old descriptions that characterized them as secondary "helpmates" or reluctant pioneers. Rather, they, along with men, were main characters in the settlement drama.

See also EUROPEAN AMERICANS: Land Laws and Settlement.

H. Elaine Lindgren North Dakota State University

Fairbanks, Carol. Prairie Women: Images in American and Canadian Fiction. New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 1986.

Lindgren, H. Elaine. Land in Her Own Name. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

Muhn, James. "Women and the Homestead Act: Land Department Administration of a Legal Imbroglio, 1863–1934." Western Legal History 7 (1994): 283–307.

XML: egp.gen.040.xml