QUILTING

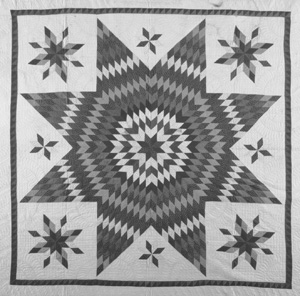

Star of Bethlehem quilt, made by Maria L. Gear Mook (1833-1914), Johnson County, Nebraska

View largerPatchwork quilts came to the Great Plains with the first European settlers who carried them in wagons and on pack mules. During the westward migration, quilts served not only as utilitarian bedding–both as pallets and covers–but as shelter when draped as overnight, tentlike structures and sometimes as doors and room dividers in the rude homes that were erected hastily in the early months of settlement.

Women traveling across the Great Plains during the mid–nineteenth century on the Oregon Trail left many records of quilts in their diaries, letters, and memoirs. Later in the century, when Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma became destinations rather than mile markers on the journey to Oregon or California, women again recorded details of the quilts they brought with them to their new homes. Among surviving writings, however, there is no mention of actual quilt making during the westward migration. There are some references to mending, sewing, and knitting on the road, but not to quilt making. Most healthy emigrants preferred to walk rather than ride in wagons. Moreover, the bumpy ride inside covered wagons made it virtually impossible to sew the precise seams required for making quilt blocks. On the other hand, women resumed quilt-making activities quickly after reaching their destinations, some almost as soon as they had a roof over their head. For example, according to family tradition, Clarissa Palmer, a homesteader in northwestern Nebraska, fashioned a silk crazy quilt from scraps her family sent to her during the first year she "sat" her claim.

Quilts and quilt makers in the Great Plains are notable for their conservative character and for their tendency to reliably reflect national trends in quilt making. This is not surprising because, by the time women in the Great Plains began making quilts in large numbers during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, an increasing number of national magazines had begun to standardize quilt-making styles and patterns. Women's magazines such as Godey's Ladies Book, Delineator, Ladies' Home Journal, Woman's Home Companion, and McCall's featured quilt patterns, articles about quilt making, and nostalgic images of old quilts. By the 1920s, newspapers– most notably the Kansas City Star but also the Omaha World-Herald and Dallas's Semi-Weekly Farm News–presented traditional and original quilt patterns on a regular basis and offered patterns that could be ordered from the paper's home office. The availability of patterns from newspapers had an enormous standardizing influence on quilt patterns during the first half of the twentieth century.

The agricultural fair, an established American tradition by the time Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and the Dakotas were settled, also helped nationalize and standardize aesthetics. Fairs and expositions were eagerly awaited annual events in all settled areas and provided friendly competition, recognition, and an opportunity to display one's needlework skills. Prizewinning quilts, no doubt, inspired imitation.

Quilt making remained a popular pastime in the United States throughout the nineteenth century. In the early 1900s, while much of the country turned to mass-produced woven blankets, the largely rural population of the Great Plains continued to use handmade quilts for bedding. Consequently, quilt making remained a vital part of everyday life in the Plains until the 1940s. Many presentday quilters from the Dakotas to Texas recall learning to sew by piecing blocks for a patchwork quilt. For generations, girls were taught to sew and to quilt by their mothers and grandmothers and were expected to do their share in making quilts and clothing for the family. Young women made quilts in anticipation of the day when they would have homes of their own. Many quilters born during the early 1900s readily recall growing up with a quilt in progress in a quilting frame in their homes. Often the frames were suspended by ropes from the ceiling and were raised and lowered as necessary.

Because quilting had never gone out of style and quilts had never gone out of use in the largely agricultural Great Plains, the surge of print media attention given to quilts in the first quarter of the twentieth century only reinforced the unflagging interest in quilt making held by rural quilters of the region.

Most surviving nineteenth-century quilts from the Great Plains are star patterns. Star patterns (single and multiple) remained the most popular design among American quilters of European descent until the 1930s. The names of star patterns sometimes varied from state to state: for example, the Bethlehem Star became the Lone Star in Texas, and a fourpointed star pattern became known as Rocky Road to Kansas.

Northern Plains Indian women favored dazzling, large, single-star patterns for their quilts. Quilting, introduced by the wives of missionaries in the late 1800s, sparked a new cultural practice among Plains Indian women of the Dakotas and Montana. Quilts eventually replaced buffalo robes in the wrapping of the dead. Star quilts were, and are, given in celebration at births and to honor loved ones at graduations. And quilts–mainly star designs– always serve as a focal point in the Native Americans' customary "giveaway."

Other quilt patterns and styles enjoyed periods of popularity in the Plains. For example, log cabin quilts and crazy quilts were fad styles that swept the region and the nation between 1870 and 1900. Plains women more often made their crazy quilts of practical wool or cotton fabrics, instead of the silks favored by eastern women. During the 1920s and 1930s a hexagon-based mosaic pattern called Grandmother's Flower Garden, as well as the Double Wedding Ring, Dresden Plate, and Nine Patch patterns rose in popularity. They remained among the most prevalent patterns for quilters of European descent until the 1960s. A resurgence of interest in quilting began in the 1970s and continues in the twenty-first century with quilters from Texas, Kansas, and Nebraska at the forefront of the revival.

See also GENDER: Quilting Circles.

Patricia C. Crews University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Brackman, Barbara, Jennie A. Chinn, Gayle R. Davis, Terry Thompson, Sara Reimer Farley, and Nancy Hornback. Kansas Quilts and Quilters. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993.

Crews, Patricia Cox, and Ronald Naugle, eds. Nebraska Quilts and Quilt Makers. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991.

Yabsley, Suzanne. Texas Quilts, Texas Women. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1984.

XML: egp.fol.037.xml