FOLK ART

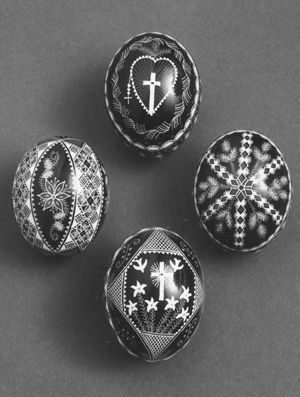

Ukrainian Easter eggs made by Angie Chruszch of Belifield, North Dakota

View largerFolk art of the Great Plains is as broad and seemingly limitless as the landscape itself. However, the lines of distinction between what is, and what is not, folk art often blurs, just like the line between the sky and the land in a Great Plains horizon. Yet folklorists generally agree that folk art is a complicated whole comprised of a number of integrated parts, with some more prominent than others.

First, a shared sense of identity among the individuals who comprise a distinctive group is key. The ties that bind the individual to the group and are the foundation for tradition include a shared language, culture, ethnicity, history, occupation, community, region, and religion or spirituality. Folk art is rooted in a tradition. The art often serves as a way to reaffirm the individual's group identity, as well as to communicate to others who they are, what they believe, and where they came from.

Second, the process and form of folk art is influenced heavily by a community sense of artistic value that changes and adapts from place to place and through time. That is not to say there is no room for the artist's individual creative expression. There is freedom, but within the boundaries of the community's artistic standards, based on its shared sense of tradition. This applies not only to the form of the art but also to the process by which that art is created. For example, within a community of Ukrainian Easter egg artists, the proper process for the creation of a decorated egg begins with a prayer to the Virgin Mary to guide the hands of the artist.

Third, folk art generally passes from one generation to another informally by way of example, observation, and word of mouth. It is usually learned outside of formal educational settings and institutions. For example, a German Russian blacksmith who makes decorative wrought-iron grave crosses may enlist one of his young sons to help him in the shop. The son soon learns the proper process and form for making cemetery crosses simply by observing and working alongside his father.

Finally, folk art is often part of a larger cultural context. It plays an active role in the lives of the community. Ukrainian Easter eggs are not made just for art's sake. They are taken to the church on Easter Sunday to be blessed by the priest. Some Ukrainian traditionalists will then take one of those eggs and bury it in the corner of one of their fields, thus ensuring a bountiful harvest. Similarly, a Native American ceremonial bag decorated with porcupine quills is not just a piece of art to be admired; it also may be used to hold a sacred pipe that is the focal point of various ceremonies.

Much of the folk art of the Great Plains stems from tribal or ethnic identity. Plains Native American and First Nation groups excel in a wide range of folk arts, from star quilts used in giveaways, naming ceremonies, and even funerals, to basketry, beadwork, and porcupine quillwork used to adorn everything from moccasins to horse masks and cigarette lighters.

The Spanish and Mexican influence, which took root in the Great Plains in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, is still found through folk arts, such as intricate needlework and the carving and painting of revered Santos, or images of Catholic saints, by Hispanic folk artists. The French influence, which spread through the fur trade into the Prairie Provinces in the eighteenth century, can still be seen in the jigs, reels, and fiddle music of the Métis people, who are descendants of French, Irish, and Scottish fur traders and Native Americans. The farmers and cowboys who followed in the nineteenth century established enduring occupational folk arts, such as wheat weaving, cowboy poetry, and decorative spur- and saddlemaking.

Subsequent immigration of many eastern and northern European peoples in the late nineteenth century brought to the Plains such folk arts as colorful Polish paper cutting, Norwegian needlework, Czech Easter eggs decorated with designs cut from wheat straw, Greek woodcarving, lively polka music, and much more. Added to this is the relatively recent influx of new immigrants: Cambodians who brought their tradition of story-cloths, Vietnamese who brought the Dragon Dance, Armenians from Azerbaijan who brought copper bas-relief work, and Sudanese and Congolese who brought adungu music.

Just as ethnic, tribal, or occupational identity is often at the core of folk art, so too is a sense of religion or spirituality. It is also important to remember that both identity and spirituality are shaped in subtle ways by the natural environment. Thus, the environment has an influence in the shaping of folk arts, especially through time. The natural environment of the Great Plains is one of vastness and distant horizons, with a sun that always looms large. The environment is strong and stark, yet delicate and colorful. People at first glance may see the sameness of an immense sky, but the brilliance of a Plains sunset ends the day. People notice oceans of grass or wheat, but all the while there are tiny, colorful crocus flowers waiting for the watchful eye. The Great Plains is given to periods of boom and bust, to cycles of life and death, flood and drought, to the seasons that are keenly felt, and to renewal. People incorporate what they see and experience around them. The natural environment of the Great Plains gives folk art in this region a distinctive feel. This can be illustrated through examples of motifs from nature found in the folk art of two ethnic and occupational (farming) groups.

The Ukrainian Easter egg tradition is a pre-Christian art form that was tied to spring fertility rituals, in recognition of the cycles of birth, death, and rebirth in nature. Animals, flowers, birds, and insects are some of the nature-theme motifs used in this delicate and colorful tradition, whereby images are applied to an egg through a batik method of dyeing. With the advent of Christianity, that spiritual notion of life after death was readily applied to the crucifixion of Christ. As Ukrainians moved to the Great Plains, they brought with them the Easter egg tradition. Some of the nature-theme motifs used in the Old Country continued in the new. Others were discarded and replaced by motifs more indicative of the artists' new home. Two motifs that have continued, and seem to have grown in popularity in the Plains, reflecting their centrality in the landscape, are those of wheat, a symbol of fertility, and the sun, a symbol of God and rebirth.

The strong, stark German Russian wroughtiron cemetery crosses also often contain motifs from nature. These beautiful crosses are eerily representative of the landscape. Some crosses are made with a half-circle arcing from one end of the horizontal bar to the other like a setting or rising sun on a flat and expansive horizon. Waving upward from the sun are iron strands of wheat. These crosses immortalize silently, yet poetically, the memory of the deceased with symbols representing shared religious beliefs of life after death: a prominent cycle observed in the natural environment that surrounds these Plains folk.

Troyd Geist North Dakota Council on the Arts

Dorson, Richard M., ed. Handbook of American Folklore. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983.

Geist, Troyd A. From the Wellspring: Faith, Soil, Tradition. Bismarck: North Dakota Council on the Arts, 1997.

Sherman, William C., and Playford V. Thorson, eds. North Dakota's Ethnic History. Fargo: The North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies and North Dakota Humanities Council, 1986.

XML: egp.fol.012.xml