PRAIRIE FILMS

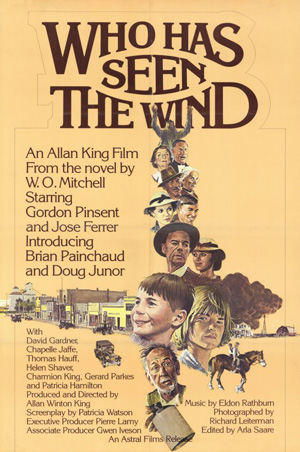

Film poster for Who Has Seen The Wind (1977)

View largerThe basis of a regional culture is a common history and geography. The history of the Prairies, a history of colonial expansion and exploitation, has provided the basis for many a yarn and many an artistic work. In terms of geography, the look of the land and its unyielding climate have inspired many to write and paint and to make films. It may not be possible to identify a specific type of film called a "Prairie film," but over the years there have been attempts to capture and transmit Prairie culture in cinematic form. A completely satisfying cinematic reflection of the Prairie experience has yet to be created.

With cinema, as with publishing and some forms of visual art, the demands of the marketplace must also be taken into consideration. Certainly, the Prairie region has been its own marketplace. Some films have recuperated their costs within the region. However, production gatekeepers expect financial success, which often means raising money by distribution beyond the Prairies.

When Hollywood became a world center for film production, producers realized that Prairie history and geography could be exploited in one of the most successful film genres: the Western. By the time Edwin S. Porter made The Great Train Robbery in 1903, readers of pulp novels had already developed a taste for stories of cowboy heroes and villains, so it made sense to bring these characters to the movie screen. Westerns could also employ the appealing choreography of horse and stagecoach chases, gunfights, and powwows.

Westerns have been successful in the marketplace, but the genre is extremely restrictive in terms of plot conventions. We must look to independent filmmakers to provide us with films that explore the finer aspects of the Prairie experience. Independent filmmakers also have to make money. Production costs for even a short documentary film can be thousands of dollars per minute. Government and private foundations provide some funds for independent production, but they tend to place some creative demands on the filmmaking process. When funding institutions reside outside the Prairies, filmmakers face a battle to tell regional stories that are true to their cultural roots.

Some of the best cinema reflections of the Prairie experience can be found embedded in films whose purpose is not necessarily art but some form of communication or commerce. Educational films, industrial or promotional films, television "movies of the week," and in some cases commercial feature films have contained scenes or elements that could be said to reflect the Prairie experience.

One of the first Prairie films was also one of the first films made in Canada. James Freer, a Manitoba farmer, made a film of farm life in 1898. The film was sponsored by the Canadian Pacific Railway to promote, in England, the sale of land on the Prairies. No prints remain of this first Prairie film, though it has been much talked about, but one can speculate: being a promotional piece, it is unlikely that it contained images of blizzards or other elements illustrating the harder aspects of life on the Prairies during this period.

A long drought in regional production occurred between 1925 and 1950. A few educational films and documentaries appeared, but cinematic storytelling was, for the most part, left to Hollywood. The results have been disappointing in their slavish use of Hollywood conventions and stereotypes.

When television came to the Prairies in the mid-1950s, tv stations produced some documentaries as part of their mandate to reflect the region for their viewers, usually in the form of hard news reportage or promotion of local events and institutions. The National Film Board of Canada offered other opportunities for the representation of Prairie themes and stories. Notable NFB films of the 1950s include Corral (1954), about an Alberta cowboy rounding up and breaking wild horses, and Paul Tomkowicz: Street Railway Switchman (1954), based on the elderly Tomkowicz's account of working on the Winnipeg street railway line on a cold winter day.

Drylanders (1964), one of the first feature film productions of the NFB, tells the story of a family of settlers who arrive from eastern Canada in the late 1800s to claim a piece of land. The film includes images of the family making their way west with an oxen cart, building a sod hut in which to live during their first winter, welcoming their first bumper crop of wheat, then watching as the land blows away during the "dirty thirties."

The 1970s was a period of expansion of the Canadian motion picture industry. Money was available in the form of loans and tax incentives through the Canadian Film Development Corporation (CFDC), later Telefilm Canada. Some government- and foundation-funded feature films have been successful at telling a Prairie story while managing to make money for their producers. These include Who Has Seen the Wind (1977), based on W. O. Mitchell's coming-of-age novel; The Hounds of Notre Dame (1981), based on the early years of Père Athol Murray at Notre Dame College in Wilcox, Saskatchewan; and Why Shoot the Teacher (1978), based on the Max Braithwaite novel of the same name.

In the 1980s and 1990s film development corporations were formed in Manitoba, Alberta, and Saskatchewan to supplement federal government funding from Telefilm Canada with provincial government funds. The budgets of SaskFilm and other Canadian film agencies help to finance the one-to-four-million- dollar movies of the week destined for the pay television market. These films employ some regional actors and craftspeople and use regional locations. Unfortunately, the locations are seldom identified within these films and instead appear as generic U.S. cities. The stories for these movies are chosen for their wide commercial appeal rather than their regional flair.

Regional filmmakers are unable to gain significant funding for their projects because regional films are not deemed financially viable. Telefilm Canada and provincial film development agencies seldom fund a project unless a large percentage of its budget has been secured from a major broadcaster or distributor. A regional story by a regional writer is less likely to gain the cooperation of a mainstream coproducer or broadcaster.

Clearly, it is up to Prairie filmmakers themselves to depict the Prairie experience in a form that avoids stereotypes but manages to entertain a wide audience well enough to attract adequate funding and distribution both within and outside the region.

Gerald S. Horne Burnaby, British Columbia

Clandfield, David. Canadian Film. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Horne, G. S. "Interpreting Prairie Cinema." Prairie Forum 22 (1997): 135–51.

Magder, Ted. Canada's Hollywood: The Canadian State and Feature Films. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993.

XML: egp.fil.056.xml