THE PLOW THAT BROKE THE PLAINS

The Plow That Broke the Plains

View largerIn May 1936, as the people of the Great Plains battled against the combined effects of over-production, drought, and depression, the federal government released The Plow That Broke the Plains. The film was part of a massive campaign by the federal government to convince farmers and ranchers that the search for windfall profits in the West had resulted in misplaced settlement, misuse of the land, and ultimately the great dust storms that ravaged the Great Plains in the 1930s.

In 1935 Rexford Tugwell, the head of the Resettlement Administration, recruited Pare Lorentz to produce a film that would explain the causes of the Dust Bowl. The film also made a strong case for resettling destitute farmers, for retiring marginal farmland from production, and for restoring grasslands in the West. The twenty-eight-minute film, which cost $19,260 to produce, included a highly emotional musical score by Virgil Thomson and was narrated by Thomas Chalmers. Although the movie industry complained about competition from a government-produced film, The Plow That Broke the Plains was shown in independent theaters, school auditoriums, and other public meeting places throughout the country. It was seen by 10 million people in 1937 alone and would become one of the most widely viewed films in American history. The film is still shown to audiences throughout the country to explain the economic and ecological disasters that struck the Plains during the 1930s. The film was, however, instantly controversial. It has since become part of an enduring historical debate about the past and the future development of the Great Plains.

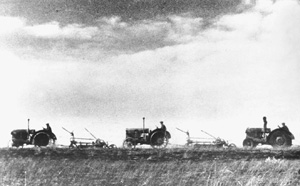

The heart of the controversy about the film, then and now, was the interpretation by Lorentz and other New Deal farm experts that much of the Great Plains was unsuited for agriculture. While soft music plays in the background and scenes of acres of lush, billowy grassland appear on the screen, the film's narrator explains how beautiful the unspoiled Plains had been before the period of European American settlement. Then, as the music grows louder with increasingly harsh tones, the film shows the movement of cattlemen onto the Plains, the coming of railroads and land speculators, and finally waves of homesteaders and farmers with horses and gang plows breaking up Great Plains grasslands. The film then moves to the World War I era, when farmers enjoyed high prices and seemingly unlimited prosperity. As the music reaches a feverish pitch, the film shows giant plows, often lined up side by side in rows, plowing under millions of additional acres of grassland. Then, after the screen goes momentarily black, the film shifts to the 1930s. The music becomes dirgelike; the Plains are now pictured as a desolate wasteland. A steer's skull, bleached white by the sun, is shown wedged in the dirt. Poor farmers, their homes nearly covered by mounds of dust, are shown running to ramshackle houses to escape the relentless dust storms that sweep across the Plains.

While many contemporaries blamed farmers and ranchers for exploiting, without regard for the environment, the resources of the West to their own advantage, Lorentz focused the blame for the ecological disaster on mechanized agriculture rather than unthinking greed. Still, the message of the film was clear: the great plow-up was a terrible mistake. At the end of the film, as thousands of refugees flee the Plains, the narrator concludes that 40 million acres of land have been totally ruined and another 200 million acres badly damaged. The film ends with a troubling question: "What is America going to do about it?"

While the film was generally hailed as a cinematic triumph, many contemporaries questioned Lorentz's understanding of the history of the Great Plains. First, critics pointed out that Lorentz had deemphasized the impact of the drought and had exaggerated the importance of agricultural expansion to explain the origins of the Dust Bowl. Second, critics contended that Lorentz had created a false impression that the entire Great Plains area was a Dust Bowl. In their view Lorentz had overlooked the diversity and vitality of the Great Plains economy and had undervalued the quality of farm life, even in the Dust Bowl areas, to make the case that substantial areas of the Great Plains should be turned back to grassland. Finally, although Lorentz had generally pictured farmers as victims of modern technology, his critics insisted that he had presented a negative and unfair image of Great Plains farmers, who were, they argued, conscientious stewards of the land. The film's critics insisted that the Plains was suitable for agriculture in spite of the dust storms and that prosperity would return to the farm economy with the return of rain.

It can be argued that the most important impact of the film was that it focused discussion on the future of the Great Plains and underscored the need for a comprehensive soil conservation program. The film, however, obviously did not settle the question about whether land in the Great Plains region, and particularly in the western Plains, should be used for agriculture. The same questions that were debated in the 1930s are still debated today, particularly during periods of drought and low farm prices.

See also MUSIC: Thomson, Virgil / PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT: Dust Bowl.

Michael W. Schuyler University of Nebraska at Kearney

Hurt, R. Douglas. The Dust Bowl: An Agricultural and Social History. Chicago: Nelson Hall, 1981.

Snyder, Ralph. Pare Lorentz and the Documentary Film. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968.

Worster, Donald. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Previous: Oklahoma! | Contents | Next: Prairie Films

XML: egp.fil.055.xml