DRYLANDERS

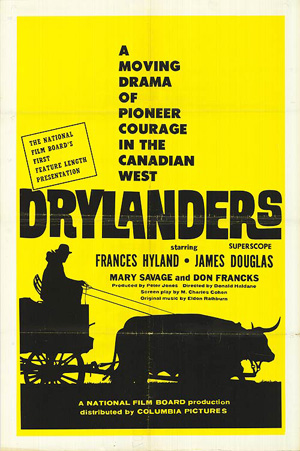

Drylanders theatrical release poster

View largerDrylanders (1963) was the first feature film made by the National Film Board of Canada. Directed by Don Haldane, it chronicles thirty years in the lives of a family who homestead, farm, live, and suffer under the power of nature in the Great Plains. The film was made on location in the Swift Current area in southwestern Saskatchewan in 1961, premiered there in 1963 to an enthusiastic audience, and went on general release in 1964. Originally planned as a television program for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, which showed little interest in it, it became a ninety-five-minute black-and-white feature, which was reduced to seventy minutes for general release and is now available in four parts for teaching English as a second language.

The story is organized in two major sequences, 1907–9 and 1928–38. It begins in the spring of 1907 after the terrible winter of 1906– 7, when Dan (James Douglas) and Liza Greer (Frances Hyland) and their two small sons arrive at their quarter section, which is a survey post, the major feature on that treeless land. There is a sod house building bee, a dance, a blizzard, and the first crop–and the hail that destroys it. That sense of hope and disaster is a prelude to the more devastating second sequence: the bumper crop of 1928 is followed by the great drought, during which the younger son (Don Francks) leaves for the city, the older son (William Fruet) stays (though there is only dust), neighbors leave, the father dies without hope, and the rains come, leaving Liza to say at the end of the film, "We're starting over again."

Between these two sequences a long montage, sometimes using license plates to chart the passage of time, disposes of World War I, in which the eldest son fights, his marriage, and the many years of good times on the farm. The montage, however, is out of sync with what goes before and comes after–the sequences that evoke an emotional response to the joys and tribulations of the Greer family. Are those invisible twenty years part of the twenty-five minutes Haldane was forced to cut? There is a successful second montage of the younger son walking the city; the closed warehouses, shut gates, soup kitchens, owners shaking their heads, letters home, riding the rail, and so on succeed, in the method of Eisenstein, to create a powerful metaphor for the unemployed single man in the city.

Drylanders is a film about farmers and nature, not about farmers and markets. There are haunting images of the Greers against the beautiful and harsh environment: the oxen and cart against a prairie sunset, the father disappearing over a snowbank in a blizzard, the dust swallowing house and barns, the lone farmer standing tall in the field. There are, however, no banks, no cost-price squeeze, no grain exchange, and no farmer protests. We know the drought eats money as well as hope, but there's no boom-bust to accompany it.

The film is really about the human heart and farming the Great Plains, not about the balance sheet. A central theme is hope and its obverse, despair, which is the trajectory the father suffers. It is his optimism and hope that bring the family west and help him survive the growing skepticism of his wife and early setbacks. When he loses all hope during the Depression and dies in 1938 after years of despair, that's a terrible pattern of defeat offset only by his wife's growing resolve to stay in the place she hated and now calls home no matter what. When the minister tells her not to lose hope, she replies, "Trouble with hope is it has to be fed," and of Dan's death she says, "The prairie had betrayed him." In Drylanders no one wins easily.

In style Drylanders is a film that declares itself a film, in its voice-overs, balancing of light and shade, elaborate camera angles, long montage sequences, and obvious symbolism and poetry. There is a great deal of pleasure to be gained from its style, from the photography of Reginald Morris, the music of Eldon Rathburn (who scored more than a hundred films at the National Film Board from 1944 to 1976), the literate script of Charles Cohen, and the acting, especially that of Frances Hyland (whose "educated" pronunciation seems right for a woman of 1907), though all the performances are good.

The film must finally be judged on its ability to move us, to make us feel the hope and despair of the homesteader and farmer in the Great Plains, in this case, the prairie of Saskatchewan. That opening night audience in Swift Current felt that emotion.

Don Kerr University of Saskatchewan

Evans, Gary. In the National Interest: A Chronicle of the National Film Board of Canada from 1949 to 1989. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

Morris, Peter. The Film Companies. Toronto: Irwin, 1984.

XML: egp.fil.020.xml