CUSTER FILMS

Custer films

Hollywood has never felt particularly compelled to film its representations of Bvt. Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer's last battle at the Little Big Horn anywhere near where the actual epic 1876 battle occurred. But it is surprising to note that in at least some instances a few celluloid Custers and Sitting Bulls actually performed their cinematic battles before the cameras at various locales somewhere in between the Rocky Mountains and the muddy waters of the Missouri River.

On film George Armstrong Custer almost always has wielded an anachronistic saber, worn the wrong uniform, flown the wrong flags, and fired inaccurate pistols. But sometimes, in spite of a lack of historical accuracy, Custer's Last Stand on film has created a unique audience-pleasing celluloid world of its own making. Most film professionals take the viewpoint that historical films are more about the perception of history, not about documentary duplication of the event. And these very same directors, producers, writers, and actors have been more than willing to knowingly bend, alter, and even fabricate Custer filmland fiction to further a pet political viewpoint, give a vicarious thrill, or make a fast box office buck. Trying to convey a real sense of the Plains Indians Wars of the 1870s to an impressionable public has seldom been their concern.

The very first Custer film, William Selig's Custer's Last Stand (1909), utilized footage of a reenactment shot near the real Montana battle site intercut with scenes done in Selig's Chicago studio. But it didn't take long for early producers to discover the balmy climate of Southern California. The very next Custer film, Thomas Ince's 1912 production of Custer's Last Fight, was lensed amidst the rolling hills of Santa Monica. Ince had convinced the 101 Wild West Show troupe to winter in California so he could make use of their performers and rolling stock in a series of frontier-themed films.

Of the sixty-seven motion pictures and thirty-some television representations of Custer, at least a handful were actually filmed in southeastern Montana or nearby South Dakota, the real-life haunts of the Seventh Cavalry and their Sioux and Cheyenne adversaries. In the Days of '75 and '76 (1915) was filmed in South Dakota utilizing a local National Guard unit to portray Custer's Seventh Cavalry. Victor Mature's thespian representation of Chief Crazy Horse in Universal's 1957 film of the same name shot its brief Little Big Horn sequence right in the middle of the Black Hills.

Central Oregon was an adequate visual substitute for the Little Big Horn valley in The Flaming Frontier (1926) and Walt Disney's Tonka (1958). The Scarlet West in 1925 and The Last Frontier in 1926 opted for the picturesque mesas of southwestern Colorado and southeastern Utah. Bob Hampton of Placer (1920) did an unusual combination of filming on the Blackfeet Reservation near Glacier National Park, Montana, and Fort Huachuca in southern Arizona, where the all-black enlisted men of the famed Tenth Cavalry stood in for the Seventh Cavalry in vast panoramic shots filmed from high atop a hovering signal balloon.

Cecil B. De Mille's 1936 epic, The Plainsman, staged most of the film's large-scale battle scenes with a second unit near the Tongue River in Montana, only to see most of that footage then used as back projection for principal scenes filmed at sound stages on the Paramount lot in Los Angeles. When Paramount revisited the Custer battle with Warpath in 1951, the same Tongue River area was used again along with a partial reconstruction of Fort Abraham Lincoln built at the Montana State Fairgrounds in Billings.

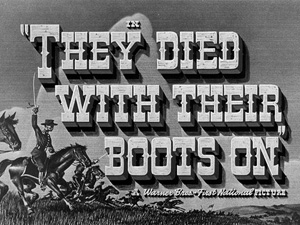

The most famous celluloid Custer motion picture, Errol Flynn's starring vehicle They Died with Their Boots On (1941), was shot exclusively on the Warner Bros. Studio Ranch in Agoura, California, a scant twenty miles from Warner's main lot in the Los Angeles suburb of Burbank. No film has had more influence on the public's perception of Custer than this epic, until the release of Little Big Man in 1970. If Errol Flynn's Custer is rambunctious and overzealous, he is also loyal and courageous, all traits that, whatever else his faults, the real Custer exhibited time and again. If the film is incredibly inaccurate history, the tone of Flynn's characterization still rings quite true of the real man.

Since 1970 filmmakers have tried to get as close to filming on the real battlefield as possible. Little Big Man (1970), ABC's miniseries of Evan Connell's best-selling book, Son of the Morning Star (1991), and tnt's cable television movie Crazy Horse (1995) were all shot in the Billings and Hardin areas, just a stone's throw away from the hallowed marble markers on the real Custer Hill. But in 1997, when Robert Redford wanted to feature the current Little Big Horn National Battlefield in his contemporary western The Horse Whisperer, he had his art director build a modern-day representation near Livingston, Montana, 140 miles west of the actual location.

Perhaps therein lies the magic of Hollywood's enduring fascination with Custer. Whether Custer is a hero or a villain, a major character or a minor supporting player, his buckskin jacket and long hair are immediately recognizable. For some these objects represent the white man's sins; for others they are the visual representation of heroic legend and myth. Custer's appeal on a medium like film is obvious; he is the most adaptable of visual symbols that represent the American West. Villain, hero, fool, misunderstood warrior, whatever the times have called for, filmmakers have molded George Custer into the figure that best suited their needs. There is no reason to think that will change in the future.

See also IMAGES AND ICONS: Custer, George Armstrong.

Dan Gagliasso National Cowboy Hall of Fame

Dippie, Brian W. Custer's Last Stand: Anatomy of an American Myth. Missoula: University of Montana Press, 1976.

Gagliasso, Daniel L. The Celluloid Custer. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Hutton, Paul Andrew. "Correct in Every Detail." Montana, the Magazine of the Western History 41 (1991): 28–54.

Previous: Cooper, Gary | Contents | Next: Dances with Wolves

XML: egp.fil.015.xml