GERMANS

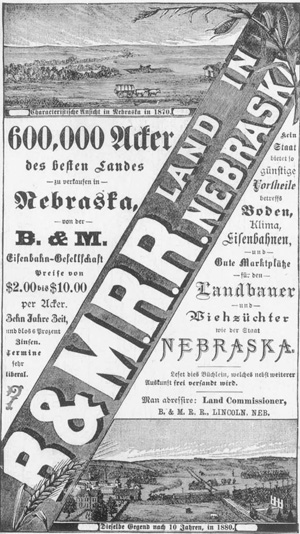

Burlington and Missouri Railroad lands advertisement in German

View largerImmigrants from the German-speaking areas of Europe (the various German states were united politically only after 1871) comprise one of the most significant elements of the population of both the United States and Canada. Germans began to arrive in North America as early as the late seventeenth century, but the overwhelming majority came between 1840 and 1890, "pushed" out of mainly northwestern Germany because of the disruption of traditional ways of life by the advent of factory modes of production, and "pulled" to North America (especially the American Midwest and the Great Plains during this period) by both real and perceived opportunities for economic betterment, due in large part to the prospects presented by landownership.

Immigrants from the German lands accounted for at least six million of those who entered the United States between 1830 and World War II, or about one in five. During most of this period Germans outnumbered any other single immigrant ethnic group, and their share of the total foreign-born in the country was never less than one-quarter. The influence of such a large immigration on the ancestral makeup of the United States is clearly reflected in late-twentieth-century census data. In 1980, for example, just over 26 percent of those sampled in the long form reported German ancestry, the largest of any single ancestral group. The number of Germans who immigrated to Canada is much smaller, and they mainly arrived between 1870 and 1935, with an interruption during World War I when Germans were barred from entry into the country. Returns from the 1996 census reveal that about 10 percent of the Canadian population claims German ethnic origin, but the numbers are much higher in the Prairie Provinces of Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Manitoba (29, 23, and 19 percent, respectively). In these provinces most "German" immigrants, however, were in fact German Russians who emigrated primarily from southern areas of the Ukraine.

One of the distinguishing characteristics of the German population in North America (especially in comparison to other immigrant groups) has been its relative degree of cultural diversity, reflected especially in the number of Christian denominations to which Germans belonged. In part this reflects patterns that had developed over centuries in Germany, whose population came to include nearly every variety of Christianity–from Catholics, Lutherans, and Reformed groups to more radical Anabaptist pietistic movements such as Amish, Mennonites, Schwenkfelders, and the Moravian church. It is not surprising, then, that nearly all of these denominations were represented among the German immigrant population in North America. The occupational profile of German immigrants was diverse, but like those of other western and northern European immigrants, it was dominated by farmers. This is largely because the process of immigration tended to be highly selective, drawing from specific socioeconomic strata. Those Germans who immigrated to North America during the nineteenth century, as revealed in recent detailed studies of German transatlantic migrations, mainly were smalltime farmers, landless sharecroppers, and servants (maids and farmhands), all of whom had been negatively affected by the social and economic disruptions that accompanied industrialization. While many came over in small family groups, a good number were young, single men and women traveling alone. A common theme underlying German immigration to North America was chain migration, the process by which generations of immigrants moved between two locales over a period of decades, creating transatlantic kinship and place-specific linkages, which often resulted in the transplantation of whole communities overseas.

German immigrants participated in the settlement and expansion of the agricultural frontier in the American Great Plains from the second half of the nineteenth century on, but their numerical presence in this frontier was not nearly as large as in the midwestern one that had come before it. Their presence in the region during the early phases of frontier expansion immediately after the Civil War was limited largely to the prairies of eastern Dakota Territory, Nebraska, and Kansas, as well as parts of central Texas. With the exception of Volga Germans (who came from a physical environment similar to the Plains), the semiarid steppe grasslands in the western Great Plains were much less attractive to most German immigrant farmers, whether migrating from the Midwest or Germany.

At the regional level, Germans, like other population groups, were attracted to the lure of free or cheap land in the Plains, largely as a result of the Homestead Act of 1862. At the local level, however, settlement patterns reflected the influence of such processes as chain migration and boosterism on the part of railroad agents and land speculators. These processes tended to direct migrants and immigrants to specific locales and resulted in literally hundreds of German ethnic "islands," particularly in the eastern Great Plains. Once a community nucleus had been established by the first generation of frontier settlers (often centered around an ethnic church), subsequent generations of migrants and immigrants, attracted to a place inhabited by those speaking a similar language or dialect, practicing a specific faith, or even hailing from the same region or village in Germany, filled in surrounding areas until an ethnic community– perhaps several townships or even a county in size–had been established. By 1910 German-born immigrants comprised an average of about 9 percent of the total population in the Great Plains states, with North Dakota registering the highest number (18 percent) and Oklahoma and Texas the fewest (5 percent).

The settlement of German immigrants in the Hill Country of central Texas differed significantly from that in the Midwest and elsewhere in the Great Plains proper. There, immigrants were participants in a short-lived but nevertheless highly influential planned settlement venture founded in 1842 in Hessen- Nassau by members of the nobility as a private joint-stock company. Among the goals of this so-called Adelsverein (union of nobles) were the alleviation of poverty and overpopulation among German peasants on the nobles' lands and the creation of new markets for goods by transplanting Germans to south Texas. The company obtained from the Republic of Mexico a two-million-acre grant situated in the Southern Plains of West Texas, and between 1844 and 1846 shipped about 10,000 Germans from many areas of central and northern Germany to Galveston through the port of Bremerhaven. Unfortunately, the company went bankrupt in 1846 before most had even arrived in the proposed area of settlement. Many became stranded along the way and settled in present-day Mason, Gillespie, Kendall, and Comal Counties at the edge of the Southern Plains, where most became successful farmers. Despite this setback, individuals and families continued to migrate to the German Hill Country on their own throughout the 1850s and 1860s. By 1857 it was estimated that 35,000 to 40,000 German-born immigrants lived in Texas; in 1850 they comprised between 60 and 80 percent of the total population in the four counties mentioned above.

In Canada, the Canadian Homestead Law of 1872 (which offered 160 acres of land for only $10) succeeded in attracting thousands of German immigrant farmers to the Prairie Provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Overwhelmingly, these Germanic immigrants were German Mennonites from eastern Europe and southern Russia. In 1874 alone, 7,000 German Mennonites established several villages near Winnipeg along the Red River. But starting in the late 1880s thousands of ethnic Germans who belonged to traditional religions such as Lutheranism and Catholicism began to immigrate to the Prairies from parts of eastern and central Europe and Russia, where they had been colonists in the early and middle decades of the nineteenth century. A smaller number came directly from Germany or migrated from Ontario or the United States. By 1911, 14 percent of Saskatchewan's population was German-born. Interrupted by World War I, immigration from Germany resumed after the war, and between 1919 and 1935 more than 90,000 Germanspeaking persons arrived in Canada. Fifty percent again came from eastern Europe and Russia, half came directly from Germany, and seven of every ten were farmers. German settlement processes in the Canadian Prairie Provinces tended to mirror those in the American Great Plains, with chain migration working to direct immigrants to specific small ethnic communities populated by those with similar religious and linguistic backgrounds, as well as similar geographic origins in Europe.

See also ARCHITECTURE: German Architecture.

Timothy G. Anderson Ohio University

Conzen, Kathleen Neils. "Germans." In Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, edited by Stephan Thernstrom. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980: 405–25.

Jordan, Terry G. German Seed in Texas Soil: Immigrant Farmers in Nineteenth-Century Texas. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1966.

McLaughlin, K. M. The Germans in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 1985.

XML: egp.ea.013.xml