EUROPEAN AMERICANS

Immigrant woman and children in front of Winnipeg Station, Manitoba, ca. 1909

View largerEuropean immigrants and their descendants created an archipelago of ethnic communities in the Great Plains largely between 1860 and 1930, although agricultural settlement began as early as 1811 in the Earl of Selkirk's colony in the Red River Valley of the North and the 1830s in the German Hill Country of southern Texas. Even earlier, European explorers and fur traders had penetrated most parts of the Great Plains. Within the flood of settlement spreading out onto the Plains after 1860 were distinctive streams of immigrants that fed ethnic communities that would survive as cultural islands for decades to come. These European immigrants, like the migrants from the eastern and central United States and Canada, encountered an unforgiving physical environment that demanded changes in their cultures, distinctive ways of life, and farming practices. Over time, depending on the volume and longevity of the migration streams and on the stability of the communities, American-born generations preserved some of their parents' cultures while adopting North American ways and creating new patterns of their own. They contributed to the successful development of new systems of agriculture on the western grasslands, actively participated in the political life of Canada and the United States, and met the challenges posed by World War I, which became the first major test of loyalty to their new homeland. In doing so, they redefined the meaning of what was required to be American or Canadian

Creating an Archipelago of Communities

Migrations created these distinctive cultural communities, and a number of other factors determined whether these communities waxed or waned. The volume of immigration to a given destination was important in forming a significant spatial cluster, and spatial clustering was another key factor. If the area had previously been largely unsettled, then immigrants might be able to realize their goal of a homogeneous community. Furthermore, if new settlers shared a common set of values and goals, and if they had a strong leader, then the likelihood of the ethnic community's success also increased. Conversely, if the migration stream was heterogeneous and heading for diverse destinations, with little interest in clustering, then it was less likely that a successful ethnic community would emerge. Proximity to a major urban center from which metropolitan cultural values emanated might weaken the cultural distinctiveness of an ethnic community. If the rate of geographic mobility was high, as it usually was in North America, then a community's longevity could be shortened and its cohesiveness weakened. However, a continuing stream of new immigrants into the community would counteract the outflow of settlers, and in those cases a transfusion model might be used to explain the continuing vitality of the community.

Streams of European immigration fed the newly formed communities in the Great Plains. A general distinction is drawn between the waves of transatlantic migration before the economic depression of 1893–96 and those between 1896 and 1914. The earlier waves carried large numbers of Germans and Scandinavians, mostly to the Great Plains of the United States; the later waves carried immigrants from central and eastern Europe, mostly to the Canadian Prairies. Before 1893 the grasslands in the United States were the strongest magnet for transatlantic migrants, but by 1890 opportunities had diminished there, so that after the depression of the 1890s the Canadian Prairies represented new opportunities not only for Ukrainians, Poles, Russians, and Hungarians from Europe but also for settlers coming northward from the American Plains. Indeed, the years between 1896 and 1914 saw considerable longitudinal relocation within the grasslands as farmers sought new possibilities in the "Last Best West." New restrictive immigration policies in both the United States and Canada in the years after World War I curtailed further European immigration to the Great Plains.

Ethnic communities in the Plains were created in part by immigrants coming directly from Europe and in part by settlers from older, well-established communities in the central Midwest and eastern Prairies. Some immigrants began farming in established communities in Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota, or Manitoba, where they worked as farmhands and earned enough cash to purchase a farm of their own farther west. In many cases individual families or several families traveled in hopscotch fashion across the Midwest before they arrived on the western fringe of settlement. The successful creation of new settlements, however, was not the result of haphazard migration. Communities were most often the result of careful planning under the auspices of a church leader, a group of businessmen, or with the assistance of a railroad company. Frequently, the stated goal was a homogeneous community that would provide economic security (and implicitly, emotional and spiritual support) for the families arriving on the frontier. The concept of the homogeneous ethnic community was supported by railroad companies, which saw its advantages for promoting land sales, but it was an idea that was not always welcomed by government.

The U.S. government tended to promote the individual landowner, and it did not assist in the creation of homogeneous ethnic settlements in the Great Plains, whereas the Canadian government adopted a policy of assisting such settlements, at least in the early years, by making block land grants to immigrants. The arrival in the Plains of large numbers of Mennonites in the early 1870s from southern Russia highlighted the differences between the approaches of the two countries. President Ulysses S. Grant refused to assist in creating the homogeneous settlements that the Mennonites desired. Such communities could be formed by Mennonites homesteading government lands and by purchasing intervening railroad lands, but they would have to do it without government support. The Canadian government, however, set aside two large blocks of land in southern Manitoba exclusively for Mennonite settlement. Within twenty years, however, the Canadian government had changed its mind and thereafter discouraged large block settlements, although it made a brief exception in the case of Doukhobor communities after 1900.

Railroads played an important role in the creation of ethnic-group communities in the Plains. Not only did they advertise widely in western and then eastern Europe, but they also worked energetically with leaders in both Europe and U.S. midwestern communities to organize group migrations to the western grasslands. Thus, Swedes in Chicago and Galesburg, Illinois, worked with the Union Pacific in the late 1860s to found Lindsborg, the initial magnet for the development of a broad swath of Swedish communities in central Kansas. Canadian railways and land companies joined forces to sell lands to German Catholics migrating from Minnesota in the first decade of the twentieth century to create the large St. Peter's colony in central Saskatchewan and St. Joseph's colony along the Saskatchewan-Alberta border. The railways also influenced the location of ethnic communities: after 1870 railways replaced rivers as the major routeways along which settlers traveled to the agricultural frontier, and railways created towns along the tracks to serve as markets and supply points for the surrounding agricultural hinterland.

Settlers from the United States crossing the land

View largerEthnic communities in the Great Plains often began with the creation of daughter colonies, the offspring of communities in the eastern and central Midwest and Manitoba. Frequently, church leaders organized the initial settlement and negotiated with the railroads for favorable terms of transportation and land purchase. Through an intricate network of contacts extending to Europe, pastors also attracted new immigrants to emerging settlements. Thus, the populations of young communities were often comprised of newly arrived Europeans as well as those who had lived for several decades in North America. In the case of the Canadian Prairies there were fewer daughter colonies, and less east.west migration, than in the United States. Nevertheless, in both countries, the new communities often included families with some previous farming experience in North America.

Environmental Adaptation

Few European immigrants, regardless of time spent in North America, had adequate experience to prepare them for the Plains environment. Conditions were markedly different from the central Midwest and vastly different from their homelands in northern and western Europe. Only those who came from eastern and southern Europe, especially from the Russian steppes, had encountered environments with similar challenges to farming. The grasshopper plagues that swept the Plains states in 1874 and 1876 were only one of the many natural hazards to induce fear, anxiety, and discouragement. Prairie fires, violent thunderstorms, occasional tornadoes, sudden blizzards, and hailstorms were among the most disturbing of nature's trials to test the pioneers' mettle. Perhaps most unsettling of all was the persistent and subtle problem of drought. Changes in the amount of moisture available for crop growth due to differential rates of evapotranspiration stymied not only the immigrant but also American farmers in the Plains. In the Canadian Prairies these problems were compounded by the short growing season and the danger of spring and fall frosts.

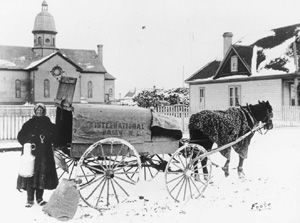

Galician woman delivering milk, Manitoba, ca. 1890–1910

View largerThe physical landscape created its own psychological stresses. The very flatness of the Western Plains created a sense of anomie even in the most closely knit ethnic communities. A great dome of sky stretched to the seemingly endless horizon, accentuating the smallness of the human scale and the vulnerability of human endeavors. The human landscape further unsettled those who were used to the compact, tightly defined geography of the densely populated European lowlands. As the grasslands were domesticated, field boundaries and roads accentuated a new rectilinear geometry in the landscape that heightened the sense of alienation and intensified the differences from the European homeland. There was no way that the Old Country patterns of social life and economic activity could be replicated in the Great Plains.

Economic forces also bore down heavily on settlers. The pioneer phase of settlement was shorter in the Plains than it had been in the central Midwest: the influence of market pressures on farming were brought to bear more rapidly than farther east as railroads increasingly penetrated the American Plains in the two decades following the Civil War. In the Canadian Prairies, both settlement and the railroads mainly came later, after the 1896 depression, and European farmers, many with only limited experience of the pressures of commercial agriculture, had to adjust rapidly to the demands of the North American marketplace. European ways of doing things, including European patterns of farming, could not survive for long in the face of an austere natural environment, changing mortgage rates, and fluctuations in the market price of farm produce. New systems of cropping and livestock farming necessarily had to be adopted in the Plains.

On first arrival, some European settlers tried to generate cash with a specialty crop or activity that would help them get on their feet until the farm became fully operational. Swedes grew broomcorn, for example, while Mennonite communities produced watermelons and silkworms in the earliest days. Other specialty crops included sunflowers, tobacco, and sugar beets. Ukrainians in Canada gathered ginseng root as a means of earning cash in the first years. Soon, however, immigrant communities adopted one or both of the great cash crops grown in the central Midwest and carried out onto the Plains—wheat and corn. Over time the viability of these two major cash crops would be tested by drought, and farmers adopted new crops resistant to moisture shortages (such as alfalfa and sorghum) or more suited to the short growing season on the Canadian Prairies (such as fast-maturing wheat and the hardy grains). Immigrants, especially those coming from southeastern Europe, where environmental conditions most closely approximated conditions in the Plains, often led the way in developing dryland farming techniques and other innovative strategies. Much has been made of the German Russian Mennonites' role in introducing hard winter wheat in central Kansas, which led to the growth of the winter wheat belt in Kansas and Oklahoma, but of more lasting importance was their ability to figure out new patterns of cropping and livestock farming and new dryland farming techniques, the best approaches to agriculture for more than fifty years from North Dakota to Oklahoma. American farmers, as well as other European immigrants, soon learned from the German Russians' success. European immigrants learned to become flexible, giving up the labor-intensive methods they brought with them and adopting the extensive-farming approaches that were better suited to the Plains. Similarly, on the Canadian Prairies new strains of fast-maturing wheat were the key to success in commercial agriculture among immigrant communities in the years before and after World War I.

Transfer from one physical environment to another produced radical changes in the immigrants' cultures. The majority of Europeans encountered not only a different physical environment but also a different economic system from those they had known in the Old Country. Fairly rapidly the immigrants dropped the distinctive crops and European patterns of farming and adopted North American cash crops, then took out mortgages to expand and mechanize their farm operations and to provide for a new generation of farmers. In short, they quickly embraced the North American world of commercial agriculture and profit maximization, and in doing so they accepted the culture of North American consumerism, thereby modifying their traditional values according to their new circumstances.

Cultural Transformation

The issue of cultural transformation is one of the most complex problems faced by scholars in studying how Europeans became North Americans. The outward manifestations of cultural transfer from the European homeland have been readily identified and have survived for decades in the landscape of the Plains. Germans in the Texas Hill Country built half-timbered and stone houses and lines of rock fences, Mennonites attempted to duplicate village patterns of settlement in reconstructing their communities in Manitoba and Kansas in the 1870s, Scandinavian communities had their distinctive smokehouses, and immigrants from Russia built summer bake ovens outside the farmhouse to cope with summer heat. But deep-seated changes in the cultures of the immigrants–in their mores and most closely held values–are not so easily identified, measured, and tracked in the adaptation to the new milieu.

These mores and values were reflected in the religious beliefs of the community, with the church playing a defining role, frequently circumscribing the behavior of its members. In German Catholic and Lutheran communities the churches defined moral behavior in ways that clearly reflected their European antecedents. German churches were perhaps less restrictive and their members more permissive than in other churches. The Swedish Lutheran Church has been described as straitlaced and puritanical in the early years: dancing, drinking, and card-playing were forbidden, a clear example of the transfer of mores directly from Sweden. The most extreme examples of this transfer can be found among Anabaptist groups such as the Mennonites. Church music, dancing, and smoking were outlawed, although the use of alcohol was permitted. Over time these patterns changed as the church relaxed its strictures: German gospel hymns were allowed by the late 1890s and social constraints on youthful Mennonite behavior were also loosened. Some Mennonites swung toward temperance and against the repeal of Prohibition in the 1920s as part of a drift toward Americanization. In general, however, churches acted as a disciplinary and conservative force in preserving the core values of communities well into the twentieth century.

Immigrants were mostly drawn from the conservative peasant class in Europe, and that conservative outlook persisted for generations in North America. Historian Oscar Handlin even suggested that immigrants became more conservative than their relatives who remained in Europe. That conservatism was reflected not only in religious practices but also in social and economic behavior. The foreign-born were more fiscally conservative, less keen to borrow than their American-born neighbors. Such traits, stemming from their peasant backgrounds, stood them in good stead in their struggle to establish themselves in the Plains. Norwegians, who had no experience making a living in grasslands, survived because of habits of industry, frugality, and perseverance, as well as community cohesiveness. Swedes were also described as patient, honest, and persistent, as well as hardheaded, stubborn, contentious, and tightfisted! Germans were recognized as tidy, careful, and efficient, with a strong interest in maintaining family continuity on the farm. The degree of community cooperation varied from community to community but was strongest among the Mennonites. All of these traits reflected the European peasant traditions from which Plains settlers were drawn.

The transition from European peasant to North American commercial farmer wrought fundamental changes in the immigrants' values. As their financial condition improved and farmers increasingly developed an expendable income, their pastors and priests railed against the inroads of consumerism and the loss of traditional spiritual values. As pioneer farmers expanded their operations and took out mortgages, they were increasingly drawn into the world of cash crops and profit maximization. The rise of economic individualism within immigrant communities meant a weakening of community cooperation and communal responsibility, although the sense of community did not disappear entirely. Families slowly adopted new goals in this world of capitalist agriculture, among them a concern for continuity on the family farm. The old peasant desire for land, for a farm they could call their own, survived the transition to commercial agriculture.

To be sure, elements of their old cultures survived in the transfer from life in Europe to life in the Great Plains, but survival was a selective process. Crops that were environmentally suitable and for which there was a market demand continued to be grown. Patterns of life that could be incorporated within a dispersed homestead settlement pattern also persisted. But the distinctive practices of religious worship and the constraints on individual behavior slowly changed with time as moral values and moral responsibility adapted to the North American social and economic milieu. Gradually, the values and behavior of a small bourgeois class living in small Plains towns became the norm for the upwardly mobile in rural communities, especially as the second generation came of age. These adjustments marked the first stages in the assimilation of the immigrants.

Assimilation

The term assimilation refers to the process whereby immigrants entered the mainstream and became indistinguishable from other members of American or Canadian society. In the United States, Frederick Jackson Turner proposed that the western frontier acted as a crucible in which immigrants shed their European heritage and intermarried to create a new nation of Americans. His "frontier thesis," however, was more a statement of ideals than an observation of reality: he seemed to ignore the presence of large, clustered ethnic settlements on the grasslands where assimilation, insofar as it existed at all, proceeded at glacial speed. But where the migration streams to frontier communities were heavily mixed and where the Europeans demonstrated a weak interest in clustered settlement, assimilation could be fairly rapid. Certainly, the adoption of the English language was necessary in small, dispersed communities because it gave the European immigrant access to a wider world of commerce, politics, and North American culture.

Biological assimilation presents a more complex picture than does linguistic assimilation. Religion represented a major barrier to intermarriage, particularly between Protestant and Catholic immigrants and to a much lesser degree within various branches of the Protestant faith. Although the rate of exogamy (marriage across national lines) was moderately high within groups of Catholic immigrants, relatively few Catholics married their predominantly Protestant American neighbors. But even among Protestant immigrants, relatively few married Americans–those from the British Isles led the way, followed by the various Scandinavian groups; few Slavic immigrants engaged Americans in marriage. On the other hand, biological assimilation was fairly rapid in small communities where the choices were limited: immigrants were obliged to find marriage partners among their American or other European neighbors. For many immigrant groups, however, exogamy was generally discouraged; it was even considered a sin among the Dutch of Montana. After World War I the rate of biological assimilation slowly began to increase, but not until well after World War II did exogamy rates in most European ethnic groups rise above 50 percent.

By contrast, European immigrants quickly adopted American material culture. The use of distinctive architectural styles and materials in home building soon gave way to the construction of American houses. Exceptions to this general rule can be found among Mennonite and Ukrainian settlers, especially on the Canadian Prairies. In the American Plains the Mennonites discarded their Russian-style houses with thatched roofs, in addition to the farm tools and implements they had brought over, within twenty years of their arrival. The rectangular survey system in both Canada and the United States was a powerful influence in molding the European immigrant to North American ways of economic individualism and shaping both the structure and operations of the farm.

The rate of assimilation among immigrant groups varied according to the community's size, location, and whether it was rural or urban. Generally, the pressures as well as the attractions to join the mainstream were greater in towns than in rural areas. Much also depended on the degree to which each group was perceived to be acceptable by mainstream society. British immigrants were ranked first. Scandinavians were also valued and assimilated readily, and arguments have been advanced that Swedes assimilated more rapidly than Norwegians and vice versa. Danes were thought to be more clannish, and Germans seemed to remain aloof longer than others. The Irish had encountered rejection in the cities of the Atlantic seaboard, but in the Plains resistance to them was much modified. French Canadian communities in Kansas and North Dakota were small, and they too assimilated fairly quickly. Strongly sectarian groups such as the Mennonites, Amish, Doukhobors, and Hutterites consciously resisted assimilation in varying degrees, and in many cases still do.

Doukhobor village of Vosnesenya, Thunder Hill Colony, Manitoba

View largerThe Canadian Prairies presented a different milieu from that of the American Plains. The Prairies were opened for agricultural settlement just after Canadian Confederation in 1867, which recognized that the Dominion had two founding nations, France and Britain. A balance was supposed to be maintained between the two cultures in this keystone region within Canadian confederation, but it never was. The French established a small toehold in Manitoba in the 1870s and 1880s, but it was English Canadian farmers, particularly from Ontario, who shaped the social life and the economy of the Prairies, far out of proportion to their numbers. Citizens of the Dominion thought of themselves as British rather than Canadian in the final decades of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century (a distinctive Canadian identity did not appear until after World War I and even then developed slowly). Certainly after 1890, when the railway network was being built, the British norm was in the ascendancy in the Prairie region. British immigrants, of course, were seen as the most desirable. But the large German Catholic colonies in Saskatchewan were peopled by settlers who had come from Minnesota expressly to resist assimilation, and they stood apart. New immigrant groups who arrived after 1896, such as Ukrainians and Doukhobors, were subjected to vilification in the local press. They clearly were not wanted by the local "host society." Indeed, on the Canadian Prairies one could make the case for ethnogenesis rather than assimilation among many European groups.

Ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis is the process whereby immigrants transformed themselves, became members of an ethnic group, and developed a distinctively new culture and identity. The new culture was not a replica of their Old World culture because social, economic, and especially physical environmental conditions in North America were so different from what they left behind. Immigrants often tried to retain their European language because it fostered cohesion within the community, defining their culture and identity. They clung to their churches, even though churches were subject to splits and schisms on the frontier. They married within their own group and discouraged exogamy. They easily yielded to change only in matters of material culture as they adapted to the new conditions and opportunities. They clustered in fairly homogeneous settlements because they could maintain essential services such as churches and schools and eventually institutions of mutual assistance. The larger these homogeneous settlements the easier it was for the ethnic community to develop "institutional completeness."

The ability of ethnic groups to create homogeneous settlements with a substantial "critical mass" was very important for ethnogenesis. Germans and Scandinavians, for example, streaming into the Upper Midwest and then into the Plains, homesteaded quarter-sections and later purchased the intervening railroad lands for themselves and their children, thereby creating solid ethnic settlements. As noted above, Mennonite leaders failed to persuade American federal officials to help them create exclusively Mennonite settlements. In Canada they succeeded, and the government set aside blocks of townships for Mennonite settlement in the 1870s. But by the turn of the century Canadian officials had rejected the notion of block settlements, and so newly arrived German Catholics from Minnesota settled in Saskatchewan without government block grants; instead, they followed the usual American pattern of combining homesteads with railroad lands to create homogeneous communities. Large homogeneous clusters provided advantages such as ease of communication, mutual assistance, and a population large enough to facilitate endogamy.

Survival of the language is often taken as a marker of the strength of ethnogenesis within a community. Men adopted English fairly rapidly, while women, bound to the domestic domain, retained the mother tongue and passed it on to the children. Churches also acted as a bulwark against the assimilative forces of the public school; pastors were determined to keep the traditional language alive by using it in church services and teaching it in Sunday schools, summer schools, and in after-school classes. The various branches of the Lutheran Church in German and Scandinavian communities were particularly active in preserving their mother tongues, whereas the Roman Catholic Church often, though not always, encouraged the adoption of English as a means of achieving unity among their nationally diverse adherents. The major challenge to linguistic survival came in 1917 as the United States entered World War I and a new form of nativism appeared as an anti-German campaign. Nevertheless, in many communities sermons continued to be delivered in the old language until the 1930s.

An ethnic community fostered cooperation during the pioneer period and facilitated the development of social and other services in later years as the community matured. The first concern of settlers may have been to create churches and schools, but soon other institutions appeared that brought stability and enhanced the security of the community. Colleges for training teachers were soon established, ensuring a continuing ethnic presence in local schools. Local banks organized by successful immigrants made credit available to fellow farmers, while general stores and hotels proudly announced the ethnic origin of the owner in the hope of attracting customers. In time hospitals, orphanages, and old folks' homes were built to cater to community needs. Musical groups and athletic clubs provided social opportunities for young people in the community. Consequently, some ethnic communities developed an institutional completeness that reduced needy immigrants' dependence on external services, thereby reinforcing their distinctive identity and keeping them within the ethnic fold.

Churches played a central role in the formation of a clustered ethnic community, not only because they provided religious services and could control the local public school system, but also because they exercised powerful social controls and exerted pressures to conform within the community. Perhaps the most extreme examples were (and to a degree, still are) found in Mennonite, Hutterite, and Doukhobor communities, but the pattern was also observed among others. The exercise of such power brought with it hazards, for it could lead to schism and disunity. In fact, religious fracturing was occasionally evident on the frontier and may be understood as yet another facet of ethnogenesis, as immigrants adjusted to their new circumstances and subconsciously began to work out a new identity for themselves. Most important, however, the churches fostered a sense of cohesion and preserved a sense of cultural identity, in addition to maintaining moral standards of behavior within ethnic communities in the Great Plains –just as they had done in the parent communities of the eastern Midwest.

Leadership was also tremendously important in the creation and survival of ethnic communities. Churches, though an important source, were not the sole source of leadership candidates within these communities. Teachers, newspaper editors, and occasionally politicians emerged as leaders. But lay leaders rarely challenged the religious leadership. Indeed, the two categories were not mutually exclusive–some of the early political leaders among the Swedes in Kansas were Lutheran pastors. Newspaper editors created a unique form of leadership, publishing foreign-language papers that linked local communities to a network of ethnic communities across the Plains and even eastward throughout the Midwest. These networks were often sustained by familial ties, especially where daughter colonies had been created. They kept local readers informed of events far beyond the local community and in doing so connected it to a wide network of communities of their own kind, whether German, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, or Irish, scattered across North America. The conscious realization that other communities survived elsewhere in the West and Midwest was an important factor in ethnogenesis and in the emergence of ethnic block voting in regional and national elections.

Political Participation

Newly arrived immigrants usually had little concern for politics beyond local concerns such as operating schools, but as their communities matured they were increasingly drawn into national political issues. The arcane debates over monetary issues, for example, were initially beyond their comprehension, but local social and cultural issues engaged their avid attention. Several sectarian ethnic groups (Hutterites, Doukhobors, and some Mennonites at first) did not participate in the political arena: they refused to vote, hold public office, or engage in public litigation. Within two decades, however, as Mennonite isolationism broke down and as they realized the necessity of protecting their school system, they were drawn into politics. The issues that became lightning rods for ethnic political participation were prohibition, women's suffrage, and state regulation of parochial schools, although when the financial crisis of the late 1880s and the depression of the 1890s threatened foreclosure of their mortgages, many ethnics abandoned their traditional party affiliations and supported the Populist wildfire sweeping the Plains states.

The Republican Party attracted many foreign-born in the years before and during the Civil War because of the immigrants' revulsion to slavery. The Germans in Texas rejected not only slavery but also secession from the Union and conscription in the Confederate army. As the northern Plains states were settled in the decades after the Civil War the majority of new immigrants continued to embrace the Republican Party. Protestant immigrants joined the Republican Party, while Catholic immigrants tended to become Democrats. There were exceptions, however. Some German Methodists joined the Democratic Party whereas French Canadians were mostly Republican. In Canada, British immigrants tended to be solidly Conservative. Later immigrants found the Liberal Party more welcoming.

The decade of the 1890s was a fractious one in the United States as the economic bubble burst and depression set in. Many ethnics were shaken loose from their traditional political a.liations when mortgage rates escalated and farm loans were foreclosed. Although many in ethnic communities were wary of the new radicalism (some thought it a front for a new form of nativism), which ran counter to the fundamental conservatism of the immigrant property owner, populism did indeed make inroads. The rockbed republicanism of Swedes and French Canadians in Kansas, for example, fractured as they flocked to the Populist cause. Even Kansas-German farmers abandoned their loyalty to the Republican Party, although they drew the line with "Yellin" Mary Lease on the grounds that a woman's place was in the home. Populists even found support among ethnic communities in the cities of the Western Plains.

Prohibition was another issue that shook ethnic communities loose from their traditional allegiances. Here the clash was between cultures–North American puritanism versus European immigrant culture. Most foreignborn thought the idea of prohibition was ridiculous. But the situation was complex, and a division occurred largely along religious lines: Methodists, Evangelicals, and Baptists were in favor whereas Catholics, German Lutherans, and Mennonites opposed prohibition. German Catholics, Bohemian Catholics, German Lutherans, and Volga Germans were opposed, while German Methodists and Swedish and Norwegian Lutherans supported prohibition. When Kansas went dry in 1889 many Germans defected to the Democratic Party. In Nebraska they played a crucial role in defeating prohibition in 1890. The general German opposition to prohibition was sustained through the first two decades of the twentieth century, even when the United States o.cially adopted the policy.

The other major cultural clash occurred over women's right to vote. On this issue Germans of all denominations were fairly well united against suffrage. Their stance was shared by Mennonites and many Scandinavians. Increasingly, though, Germans stood out among the ethnic communities as opponents on the battle lines that marked the clash between immigrant and American culture. In part, this was because Germans unified to make their voice effective in American politics.

In 1901 the German-American Alliance was founded as a cultural and political organization determined to preserve German culture, especially the German language, and to create a unified voice in the political arena for the protection of those issues Germans held dear. Branches were established in various Great Plains states and were effective in preserving the German parochial school system, both Catholic and Lutheran, and in opposing prohibition and women's suffrage. When World War I broke out in Europe, they were passionate in their support for the fatherland and opposed war loans and the shipment of arms to the French and British. They declared their loyalty to the United States but also insisted on American neutrality in Europe's war. All that changed when the United States entered the war in April 1917. World War I was to become a major watershed not only for Germans but also for other European ethnic groups in the Great Plains.

In the United States both major parties attracted immigrant support, but on the Canadian Prairies the two major parties were deeply divided on the question of immigration. The Conservatives encouraged immigration from Britain during the 1870s and 1880s when the Prairies were being opened for settlement. When the Liberals took power in 1896, a young lawyer from the Prairies, Clifford Sifton, became minister in charge of immigration and encouraged opening the doors to peasant farmers from eastern and central Europe, especially from the Ukraine. The level of vitriol in public discourse between the Liberal Winnipeg Free Press and the Conservative Winnipeg Telegram underscored policy differences between the two major parties and within the host society forming on the Prairies. These divisions did not lessen after 1914, and the two issues of prohibition and suffrage were intimately interwoven in Canadian Prairie politics during the war years.

Support for suffrage and attacks on alcoholism and prostitution were part of a reform program launched by Anglo-Canadian women on the Prairies with the support of farmer organizations in the years before World War I. The large number of immigrants, newly arrived in western Canada, were not yet ready to join the movement, especially when suffrage was introduced in 1916. Older immigrant groups such as the Scandinavians would be included but not the roughhewn newcomers. Although young Ukrainian women began to engage in public discussions as early as 1912, they were encouraged to emulate their Anglo-Canadian models but not to expect the same rights. Furthermore, alcoholism had been a major scourge in some Ukrainian communities in Manitoba.and local legend has it that the anti-Prohibition industry that funneled supplies across the United States border in the 1920s and 1930s originated here. Clearly, in the Anglo-Canadian view, the morals of these new immigrants would have to be much improved before full British rights could be extended to them, long after the war had ended.

World War I Watershed

The outbreak of war in Europe in 1914 had an immediate effect on Canadian immigrants, particularly those of German origin. A strong anti-German sentiment swept across the country, including the Prairies, as German-language schools were ordered to use English and German-language newspapers were closed. It was not just German-speaking Canadians who felt the force of anti-German sentiment. Those from any part of the Austro- Hungarian Empire were suspect. Ukrainians, in particular those with ambitions to establish a Ukrainian republic and those who were socialists, were rounded up and put in detention camps. However, the rights of pacifist groups such as the Mennonites, Amish, and Hutterites to refuse military service were upheld.

South of the forty-ninth parallel a policy of neutrality prevailed until April 1917, when the United States entered the war. Meanwhile, those of German ancestry, including the Mennonites, were far from cowed. The threat of an attack on the fatherland united Germans in the United States as never before. They insisted that the United States should remain neutral and avoid foreign entanglements. The German American press attacked the American media and President Woodrow Wilson for their apparent tilt toward Britain. German American communities also raised funds for the German Red Cross. In the election of 1916 Germans voted Republican, although Mennonites voted Democratic in the belief that President Wilson would keep the United States out of the European war.

The Germans and German-speaking peoples in the Plains were not alone in lining up on the German side during the initial years of the war. Scandinavians generally supported the German cause, especially Swedes, although Danes were bitterly divided on the issue. The Irish in Butte, Montana, also supported the German side, in large measure because of their fierce anti-British sentiment.

When the United States entered the war, loyalty to Germany was incompatible with loyalty to the United States. A new American organization, the National Security League and its offshoot the American Defense League, raised a voice that spread virulent superpatriotism and intensified anti-German hysteria. The superpatriots attacked the use of the German language in schools as unpatriotic. The use of German in churches also came under attack. German was forbidden in the pulpit in Montana and a Lutheran pastor in Texas was whipped when he continued to preach in German. Church congregations varied in their response to these pressures, but of all the churches the German Lutherans were most resilient.

Pacifist groups such as the Mennonites were doubly vulnerable, not only because of their use of German in church and school but also because of their pacifist principles. While some Mennonite youths from liberal congregations were willing to perform military service, there were many who strenuously adhered to traditional nonviolent principles. Occasionally violence erupted. The refusal of conscientious objectors to accept military service resulted in their vilification, and their patriotism was called into question. In North Dakota the Hutterites, who resolutely refused military service, were in an impossible position, and many of their young men were beaten and imprisoned for their pacifist principles. Many moved north into the Canadian Prairies. In Kansas some Mennonites who balked at buying war bonds were threatened by local mobs, and a few were tarred and feathered.

Although the United States entered the war later than Canada, the reaction to "enemy aliens" in the Plains was more virulent than on the Prairies. To be sure, the Canadian government created a register of enemy aliens that required surrender of firearms, monthly reporting of their whereabouts, and suppression of foreign-language journals. But Canada admitted Hutterite refugees from the Dakotas despite the opposition of Canadian veterans' organizations, and Canadian Mennonites fared better than their American cousins during the war. As the war continued, however, Canada also turned up the heat on enemy aliens in 1917 and 1918. Most discriminatory of all was the Canadian Wartime Elections Act of 1917, which deprived naturalized citizens of enemy origin of the right to vote. In April 1918 all exemptions to military service were canceled except those for Mennonites and Doukhobors. Some zealous local boards even tried to draft them. Heavy restrictions were placed on all foreign-language presses in September 1918, by which time German newspapers in western Canada had ceased publication. Pressure on German language and culture continued to build on both sides of the border as the war continued.

After the war ended, discriminatory attitudes toward foreign languages continued, and many ethnic communities accelerated their adoption of English. Non-English languages, including French, were suppressed in Prairie public schools, and "Canadianization" became the order of the day. English Canadian nativism briefly reared its ugly head on the Prairies and targeted French Canadians because of the conscription crisis in Quebec during the war. In the United States foreign-language instruction declined precipitously after the war and many parochial schools adopted English. Although the German-language press rebounded to an extent after the war, the number of Germanlanguage church periodicals and trade journals dwindled during the 1920s to about onequarter of their prewar numbers. German churches in the United States (Catholic and Lutheran) fell into the hands of leaders committed to Americanization during the 1920s, so that foreign-language use in church services and on tombstones gradually declined. During this decade the English-language press and radio made significant inroads into ethnic homes.

In politics, ethnic communities retained a distinctive perspective. They could not forget the discrimination they had experienced during the war, and the politics of revenge was practiced, for example, when the German areas of Nebraska returned huge Republican majorities after the war. In 1920 especially, Germans were not so much pro-Harding as anti-Wilson. But the deepest crisis faced by German communities was one of regional leadership. The Burgersbund replaced the old German-American Alliance in the Midwest, but the new leadership was weak. Consequently, the Germans and Mennonites supported presidential candidate Robert La Follette and his League for Progressive Political Action in 1924 and were ineffective in both major parties. They continued to oppose prohibition and women's suffrage.

Efforts to organize and unify the ethnic voice in regional and national elections failed in the 1930s as assimilation swamped ethnic identities. The failure of leadership among Germans permitted the success of Nazi sympathizers within those communities in the 1930s when Germans in general were anti- Roosevelt. The onset of World War II, however, found ethnic communities solidly within the national camp, and there was no repeat of the internal conflicts and hostilities that had marked entry into World War I. So much assimilation had taken place during the 1920s and 1930s, and so much suffering had been endured during the Great Depression, that ethnic communities blurred the boundaries that separated their identities from that of the mainstream host society.

With the possible exception of Ukrainian communities on the Prairies, where distinctive religious practices and language retention remained strong, immigrant communities in the Plains and Prairies saw a decline in ethnic solidarity. The use of Swedish and other foreign languages in Sunday church services, for example, declined in the early 1930s, and support for summer-school language instruction withered during the Depression. Second- and third-generation farmers of foreign origin in the Plains and Prairies were faced with acute problems of farm survival, during which feelings of community solidarity were strengthened, especially among sectarian ethnic groups. But in those difficult years many had come to think of themselves increasingly as Americans or Canadians.

Europeans in Urban Centers in the Plains

The vast majority of European immigrants to the Plains and Prairies lived in rural communities: they had been drawn to North America because of the opportunities in farming. Usually, small service centers emerged in which American-born merchants and professionals provided services. But if the town served a large, ethnically homogeneous community, then European immigrants would set up a general store, provide legal, banking, and other services, publish newspapers, and become community leaders. Thus, the ethnic group developed institutional completeness within these small towns. These good burghers also "set a tone"–maintained standards of behavior that became the norm for their rural cousins. Examples of such towns might include the Swedes in Lindsborg, Kansas; Germans in Humboldt, Saskatchewan; Mennonites in Steinbach, Manitoba; and the Norwegians in Northwood, North Dakota. European immigrants in the hundreds of small service centers scattered across the Plains played a key role in setting social standards and in sustaining networks of contact throughout rural communities.

A few immigrants were drawn to employment opportunities in small mining communities in the Plains. Deposits of coal and lead were exploited in southeastern Kansas in the 1870s and Oklahoma in the 1880s. Italians, who seldom went into farming, were attracted to Krebs, Oklahoma, as early as 1875 and dominated later mining communities in the state such as McAlester and Coalgate. The Irish overwhelmed the mining community of Butte, Montana, to an extraordinary degree: they owned the mines, supplied the labor, and controlled the unions and local politics until the turn of the century when Finns and Italians began to compete with them in the labor market. But in general the Irish were not drawn to mining. Italians and Poles, on the other hand, were enticed by mining companies from Oklahoma to the Crowsnest district in Alberta, particularly after 1896 when immigration from eastern and southern Europe burgeoned.

The largest urban ethnic communities were found in the major transportation centers that served as gateways to the Plains—Kansas City, Omaha, and Winnipeg. Each ethnic group developed a niche in the labor market, working in the warehouse district, in meatpacking plants, or in small manufacturing enterprises such as brewing or brickmaking. Newcomers tended to cluster in the early years of settlement in these growing cities, but large ethnic ghettos rarely persisted as they did in eastern cities. An exception was Winnipeg, where distinctive Slavic and Jewish settlements emerged in the "North End." The ethnic and class divisions in Winnipeg were especially marked as Germans and Scandinavians blended into the Anglo-Canadian majority, who also formed the city's elite. During the famous General Strike of 1919, however, Jewish and other east European immigrants joined forces to challenge the power elite in a rare display of labor solidarity, despite attempts to denigrate the strike as anti-British and antidemocratic.

Conclusion

The strategies and concepts that scholars have used to study the adaptation of European immigrants to North American society have changed over the decades. In midcentury, scholars such as Oscar Handlin focused on the social transformation of European peasants and proletariat as they created new homes in North America. In the last thirty years of the twentieth century scholarly focus shifted to the enduring cultures of these European immigrants. New emphases will no doubt emerge in the decades to come as the processes of modernization are brought into the discussion. One of the most interesting new concepts to be introduced to ethnic studies is that of the localization of culture. The concept offers the possibility of fresh insights into how Europeans transformed both themselves and North Americans.

Localization of culture refers to the ability of immigrants to embed their values deeply in a locality, not only at the level of the family or small group but also at the broader community or county level. If an ethnic group is sufficiently numerous it may take control of the local institutions of governance, education, and politics and infuse them with a distinctive character, thereby creating a "charter culture." The charter culture is reflected in the modes of social control and conformity, the public morality, the priorities in resource allocations, and the patterns of checks and balances in daily life that distinguish one locality from another. Thus, a myriad of local cultures is created, which in turn affects the development and course of mainstream culture and which ultimately may explain the evolution of its regional variants.

One of the most distinctive and as yet unexplained patterns within the Great Plains is the regional variation in sociopolitical perspectives that, for want of better terms, we may label conservative and liberal. In Kansas and Nebraska one thinks of the Bible Belt and the political support of fiery radio broadcaster Father Coughlin and Republican presidential candidate Alf Landon in the 1930s. It contrasted sharply with the so-called Red Belt of the Dakotas and Minnesota, which found expression in the political views of Henry Wallace and, later, Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern. On the Canadian side of the border there was a Bible Belt in Alberta associated with the Social Credit Party of Bill Aberhart and Ernest Manning, which contrasted sharply with the "social gospel" of Tommy Douglas and the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation in Saskatchewan. The links between these political philosophies and various branches of Christianity are easy to establish. The links to ethnic communities, and particularly to their deeply held values, are not yet clearly established. But the concept of localization of culture offers much potential for exploring those links and for clarifying the contribution that ethnic communities have made to regional and mainstream culture and politics.

Localization of culture is but one of several perspectives used in studying the making of new Americans and new Canadians in the Great Plains. The adjustment of immigrants to their environment, their assimilation or ethnogenesis, and their influence on the political, social, and cultural life of this broad region all represent other perspectives. But there can be no doubt that European immigrants made a distinctive contribution to Plains life, both in rural and urban communities. The constant ebb and flow of population, as farmers and urban workers and their families left for new frontiers farther west, or for other opportunities in nascent towns and cities, resulted in the creation of a network of family ties, ecclesiastical connections, and institutional links that strengthened and deepened the culture and identity of each community. The evidence remains to this day, for example, in western Kansas where, due to rural population decline, German Russians travel twenty or thirty miles to come together and maintain churches and social institutions and so sustain their culture. It may sometimes seem as if European cultures are fading from the bright patchwork of ethnic communities of a century ago, but the reality may also be that all along they have been forming mainstream culture as their own.

See also IMAGES AND ICONS: Last Best West / LAW: Meyer v. Nebraska / MEDIA: Immigrant Newspapers / POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT: Democratic Party; Liberal Party; Populists (People's Party); Republican Party / RELIGION: Doukhobors; Hutterites; Mennonites / TRANSPORTATION: Railroad Land Grants.

Aidan McQuillan University of Toronto

Conzen, Kathleen N. "Mainstreams and Side Channels: The Localization of American Cultures." Journal of American Ethnic History 11 (1991): 5–20.

Conzen, Michael P. "Ethnicity on the Land." In The Making of the American Landscape, edited by Michael P. Conzen. London: Unwin Hyman, 1990: 221–48.

Dawson, Carl A. Group Settlement: Ethnic Communities in Western Canada. Toronto: Mac- Millan Publishing Company, 1936.

Emmons, David M. The Butte Irish: Class and Ethnicity in an American Mining Town, 1875–1925. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

Handlin, Oscar. The Uprooted: The Epic Story of the Great Migrations that Made the American People. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1951.

Hudson, John C. "Migration to an American Frontier." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 66 (1976): 242–65.

Lehr, John C., and D. W. Moodie. "The Polemics of Pioneer Settlement: Ukrainian Immigration and the Winnipeg Press." Canadian Ethnic Studies 12 (1980): 88–101.

Loewen, Royden K. Family, Church and Market: A Mennonite Community in the New and Old Worlds, 1850–1930. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Luebke, Frederick. Germans in the New World: Essays in the History of Immigration. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

McQuillan, D. Aidan. Prevailing over Time: Ethnic Adjustment of the Kansas Prairies, 1875–1923. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

Nugent, Walter T. K. The Tolerant Populists: Kansas Populism and Nativism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963.

Schlichtmann, Hansgeorg. "Ethnic Themes in Geographical Research on Western Canada." Canadian Ethnic Studies 9 (1977) 9–41.

Shortridge, James R. "The Heart of the Prairie: Culture Areas in the Central and Northern Great Plains." Great Plains Quarterly 8 (1988): 206–21.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. "The Significance of the Frontier in American History." Annual Report. American Historical Association (1893): 199–227.

XML: egp.ea.001.xml