COLLEGE TOWNS

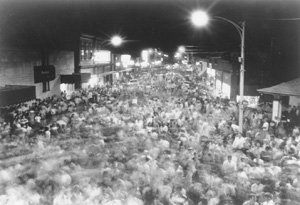

Aggieville (Manhattan) is a blur of activity after a 1984 Kansas State victory in football over the University of Kansas.

View largerMore than a dozen Great Plains cities and towns owe their development and contemporary character to the presence of colleges or universities. College towns like Lawrence, Kansas, Brookings, South Dakota, and Chadron, Nebraska, while distinct from one another because of the different nature of the schools located in them, are nonetheless similar in many ways to hundreds of other cities nationwide that are dominated by institutions of higher education. With their youthful and comparatively diverse populations, highly educated workforces, relative absence of heavy industry, and presence of cultural opportunities unusual for cities of their size, these towns stand apart from the rest of the region.

As elsewhere in the United States, many colleges on the Plains were founded outside the largest cities, so they came to have a controlling influence over the places where they were located. Colleges were placed in smaller towns not because, as is often assumed, college founders had an antiurban attitude but because small towns actively pursued colleges as a way to assure their economic survival. Rarely did the municipality that won designation as seat of a college have any special locational advantages. More often than not, it was successful because it offered the largest amount of money and the biggest plot of land or was politically adept. Backroom deals and unethical behavior were common. Town leaders in Lawrence, for example, bribed legislators deciding where to locate the University of Kansas for $4 a vote.

Most college towns remained relatively small places, with the college often serving as but one part of a diversified economy, until after World War II, when a college degree increasingly came to be viewed as a prerequisite for success. Enrollments boomed through the mid-1970s, and college towns grew rapidly as a result. As higher education institutions fueled local economic development, town leaders began to resist less desirable types of industry, and college towns became more onedimensional in the process. To some degree, they resemble company towns, with the college as the number one employer, biggest property owner and landlord, and most powerful political force. In many, the majority of the population has some connection to the college. In Vermillion, South Dakota, a town of fewer than 10,000 residents that is home to the University of South Dakota, students and staff number more than 8,000.

The most fundamental difference between college towns and the rest of the Great Plains is demographic. In a region that is growing older, college towns are ever young. Nearly half the residents of Manhattan, Kansas, home of Kansas State University, are eighteen to twenty-four years old. While many towns on the Plains are losing people, college towns are growing. The population of Brookings, home of South Dakota State University, grew 14 percent between 1990 and 2000. In a region that has long battled brain drain, college towns again are an exception. In Laramie, Wyoming, home of the University of Wyoming, 40 percent of adults have a college degree. College towns are also comparatively cosmopolitan. Students at Oklahoma State University come from fifty states and 116 countries. Residents of Stillwater, where Oklahoma State University is located, are three times more likely than Oklahomans in general to have been born outside the United States.

The nature of higher education institutions and the people associated with them give college towns distinctive personalities. Most are regional cultural centers, with the college campus serving as the focus of such activity. With their concert halls, theaters, museums, sports stadiums, parklike landscapes, and busy calendars of events, campuses serve not only as environments for learning but also as public spaces. At the University of Oklahoma in Norman, for example, the Catlett Music Center hosts concerts several nights a week. Two campus art museums feature regular exhibits. The university recently opened a thirty-eight- million-dollar museum of natural history. Millions of people visit Norman every year to attend football games, an annual medieval fair, and other campus events.

The university influence is also significant off campus. Nearby shopping areas strongly reflect the ever-changing tastes of young people and the nonmainstream orientation of many academics. In some college towns, such as Manhattan and Norman, commercial districts have developed next to campus that are separate from the city's downtown. Certain types of businesses tend to be unusually plentiful in college town business areas: bookstores, coffeehouses, T-shirt stores, bike shops, ethnic restaurants, health food stores, and, most conspicuously, bars. There are eighteen bars in a six-block area of Manhattan's Aggieville district.

The social differences that exist in college towns have also led to the emergence of distinctive residential landscapes. The large number of students is marked by the high-rise dorms of campus, the faux classicism of "fraternity row" (for example, University Avenue in Grand Forks, North Dakota), and the disheveled rental houses of the "student ghetto" (for example, Lawrence's Oread neighborhood). Most college towns also have at least one campus-adjacent neighborhood that is home to concentrations of faculty and administrators. Characterized by tree-lined streets and stately homes, these neighborhoods were often marketed directly to professors; in Norman, one such subdivision was platted as Faculty Heights.

College towns are also relatively unconventional places. The sexual revolution first played out in college towns as diverse as Lawrence, which had an active gay rights organization as early as 1970, and Chadron, home of tiny Chadron State College, where a local theater drew national attention in 1969 when it began showing X-rated movies to a largely student audience. Lawrence was a center of the 1960s counterculture and, since that time, has maintained its reputation for liberalism, once electing a state representative known as "Marijuana Mike," successfully fighting development of a suburban shopping mall, and voting disproportionately for left-leaning presidential candidates like Ralph Nader. It has nurtured poets, artists, musicians, and eccentrics. Suggestive of the different character college towns possess in a largely conservative region, a 1980s Lawrence rock band penned a song paying tribute to the distinctive nature of the Kansas college town. It was entitled Berlin on the Plains.

See also EDUCATION: Land-Grant Universities.

Blake Gumprecht University of South Carolina

Previous: Cheyenne, Wyoming | Contents | Next: Colorado Springs, Colorado

XML: egp.ct.013.xml