CITIES AND TOWNS

Cities of the Great Plains

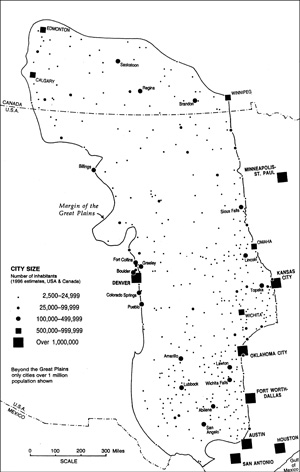

View largerCities were crucial to the European colonization of the Great Plains, yet when measured against the power of the protean natural environment, cities would play little direct role in defining the perceived human character of the region. Therein lies the paradox of urbanism in this vast territory of America, and its explanation is profoundly geographical. The primacy of cities for the region's actual development rests on two themes: the fundamental importance of urban markets in the American East and overseas in stimulating the huge demand for agricultural and mineral products that the Great Plains could satisfy, and the urban-based management of the very colonization system employed to settle people on the Plains. Furthermore, railroads, those avid servants of cities, brought settlers to the region and simultaneously provided them with an instant network of new urban sites to coordinate the supply of economic and social services the region required. On the other hand, the geographical logic of those supply lines placed the largest cities at the very rim of the region, if not wholly outside it, and so the Great Plains has evolved virtually as the hole in the urban "doughnut" of America. Consequently, the urban culture of the Great Plains is overwhelmingly a small-town culture in which attitudes and outlook are much closer to those of the rural vastnesses of their immediate trade areas than to the tempo and timbre of the big-city urban web that surrounds them on practically all sides. Only on the Canadian Prairies–unlike the American Great Plains, surrounded on all sides by terrain ill suited for the building of cities–is the hole-in-thedoughnut simile less appropriate.

Great Plains Towns in a Continental Context

Towns and cities in the American and Canadian Great Plains are among the youngest urban foundations on the continent. Few cities can trace their urban existence further back than 1860, and many towns in the region were founded as recently as the early decades of the twentieth century. Amarillo and Lubbock, Texas, Wichita, Kansas, and Regina and Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, the only sizable cities centrally on the Plains, were founded in 1887, 1890, 1873, 1882, and 1883, respectively. Associated with the youth of the region's urban places is the low level of urbanization overall. In the four states that are wholly contained within the region (North and South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas), only 49.5 percent of the population at the end of the twentieth century lived in metropolitan areas, as opposed to 79.8 percent nationally, and only five urban areas in these four states exceeded 100,000 residents. It requires no further statistics to establish that the Great Plains is a region in which large cities are only marginally important, but those geographically peripheral cities loom large socially and economically within the actual urban pattern of the region.

The other overarching characteristic of Great Plains urbanism is the enduring asymmetry of its spatial structure and national connections. The Plains was settled from the East, and its towns and cities have historically looked east for markets, sources of supply, and general inspiration. The immediate ties of commerce and urban culture on the Plains are to the large metropolises of the Middle West and, more distantly, the northeastern seaboard. Minneapolis, to take the most pronounced case, has long enjoyed an extraordinary westward reach in its economic dominance of the Northern Plains, making not only all of North and South Dakota tributary to its businesses and banking services but also the entire state of Montana. Not only Billings, at the western edge of the Plains, but Butte and Missoula in the mountains have stronger business ties to Minneapolis than to Seattle, only a third of the distance away. Similarly, within the Plains states, urban trade areas have long been hugely skewed to the west: in South Dakota, Mitchell newspapers in the 1920s were read as far west as Philip, which is three times closer to Rapid City than to Mitchell. In the Canadian Prairies, because of the triangular shape of the region, such skewedness tends to be to the northwest or north of the key urban centers.

The long distances between towns and the low population densities within so much of the region dictate that its towns and cities fulfill only a restricted range of economic and social functions, and customers seeking advanced services such as high-tech medical attention, wider consumer choice, and major sporting events often need to travel to the large cities on the region's margins to obtain them. Since the development of hub-andspoke service in the deregulated airline industry, residents south of the forty-ninth parallel have had to endure decidedly poor and remote air service. For the same reasons, manufacturing is an insignificant component of most towns and cities of the region, except for oil and gas processing in the Canadian provincial centers of Calgary and Edmonton. Industrial activity, if it is based on exports at all, is generally extremely small-scale or devoted to repair rather than fabrication. As such, urban life tends to be replicative rather than innovative and best developed in the gateway cities on its margin. These, then, are some of the abiding features of urban life in the Great Plains seen within a wider context.

Periods of Urban Life

Notwithstanding the comparative recency of towns and cities as historical artifacts in the Great Plains, their appearance on the physical landscape and in the social fabric of the region should be seen as the product of a fairly complex phasing in time and space. It is reasonable to recognize four broad phases in that emergence: town life in places established during the river and droving regime (1850s–1870s); town life during the phase of railroad colonization (1870s–1910s); urban life during the period of early-twentieth-century modernity (1910s–1950s); and, latterly, the era of urban polarization and retreat (1950s–present). Plainly, such historical distinctions are but a convenience for general understanding. The key processes attached to each phase can be found in adjacent phases, particularly when one considers geography: developments had a way of spreading from east to west over time, though very unevenly, and the retreat of urban life appears to be progressing, with similar unevenness, from west to east. It is revealing nonetheless to consider these four phases as distinct periods of social experience in the Great Plains, because each has left its own characteristic marks on the landscape and echoes within the composite outlook of the region's population.

Urban origins in the Great Plains predate the railroad. This may seem obvious, but it deserves emphasis because the greatest flows of population into the region occurred during the railroad period and thus shaped the "majority" experience that became handed down as lore through the generations. Before the 1850s, urbanism in the Great Plains was represented largely by the wealth the fur trade bestowed on St. Louis, Winnipeg, and Edmonton. As the tide of European American settlement pushed up the Missouri River and territories were organized across the Plains proper, river towns appeared on the west bank of the Missouri in Kansas and Nebraska during the 1850s. Thus, a narrow zone on the eastern margins of the Plains urbanized under a steamboat regime (essentially, a potamic or water-based colonization system), supplying both military forts planted deep on the frontier as well as the overland freighting trade, cattle droving, and the first tentative farm settlements. Towns were laid out with grandiose plats from Wyandott to Leavenworth, Atchison, Bellevue, Nebraska City, Omaha, and Florence. The river-port system was extended upriver into Dakota Territory, with Yankton and Vermillion founded around 1858, as well as along the lower reaches of the Kansas River.

These river towns owed their morphology and social character largely to their eastern predecessors on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, but they represented also the western limit of this type of urban function as transshipment points between waterways and wagon trails. The utility of great rivers as localizing arteries of commerce and population dispersion, so fundamental to America as far west as Missouri, fell foul of the shallow river conditions and uncertain water levels of the Great Plains. Settlement would have stalled had the railroads not caught up with potamic colonization on the middle Missouri River during the late 1860s. Nevertheless, the river towns of the Plains add depth to the urban record of the region and echo an early a.liation with water routes that would soon be lost.

Railroads could cross dry terrain with virtual impunity, and they spearheaded an unprecedented wave of urban and rural settlement across the Great Plains from the 1870s well into the twentieth century. This is the great era of town construction from scratch. This second and dramatic phase of Plains urbanization witnessed a standardization and corporatization of town founding, inasmuch as railroad companies developed something of a science in planting towns at suitable distances along their lines in hopes of generating maximum tra.c and perfected the art of controlling the supply of key urban equipment such as grain elevators, stockyards, coal and lumberyards, banks, and hotels, many financed and owned by businessmen in midwestern centers such as Minneapolis and Chicago. In the Canadian Prairies the pattern was slightly different, owing to the direct role of the national government in developing the railroads. However, there was no lack of uniformity in the planning and look of Prairie towns north of the forty-ninth parallel.

During this period, regional differences in the density and location of urbanization across the Great Plains became quite evident. At first, the drive to complete several trans-continental railroad trunk lines produced lonely linear corridors of towns at several latitudes across the Plains. Then, as the continental wheat belt bifurcated into two zones and surged northwestward into the Dakotas and Canadian Prairies and southwestward into Kansas, dense networks of rails and shipping towns arose in their midst. But try as they might, settlers could not establish a firm foothold in certain areas, and the West River country of North and South Dakota and the Sandhills of Nebraska would stand out as inimical to town development. Farther west, north, and south, the rangelands that stretch from Montana to Texas and the southern portion of the Canadian Prairies, which the Palliser expedition described as an extension of the Great American Desert, also proved hostile to more than minimal railroad service, and, consequently, they saw infrequent town foundations.

However, all this became framed by the heady growth of the gateway cities, those "hinge" nodes that sort the tra.c between the Great Plains and their neighboring regions. The trunk railroad pattern ensured that eventually towns like Calgary and Edmonton, Billings, Cheyenne, and Denver would prosper along the western border, while Winnipeg, Fargo, Omaha, Kansas City, Wichita, Oklahoma City, and Fort Worth would rise on the eastern margin.

During the opening two decades of the twentieth century railroads overpenetrated the productive portions of the Great Plains, a miscalculation that the first droughts of the period would dramatize. This is the last time new towns would be added to the region's network. The period lasting roughly from 1910 to 1950 can be distinguished and lent some coherence by its mixed signals of progress and retardation. While the limits were being tested, both by the last pioneering generation on the farms and by the overconfident and often overextended railroads, the era also witnessed the seepage of modernity into the entire region. Automobiles, electricity, radio, the movies, modern hospitals, and college education spread their influence across the Plains, simultaneously bringing hope of a better life from the outside as well as reinforcing how relatively backward many areas on the Plains were by comparison with more settled areas.

In the same period that agricultural science was assisting in diffusing better farming methods applicable to the dry Plains and strong demand and bumper crops produced occasional good economic times, other forces were conspiring to sort out the town system of the Great Plains in an ominous way. The mailorder business, for one, undercut the commerce of local store merchants. The "viability" of farm trade centers across the region became the worrisome watchword of the new rural sociologists, and the first patterns of differential growth between small towns and larger centers became clear. The diffusion of the automobile decreased physical isolation but simultaneously increased the geographical consolidation of retailing and other services in fewer, larger places.

After the Second World War, patterns of small-town decline across the Great Plains intensified, and they have continued unabated to the present. Broad changes in the continental organization of farming, wholesaling, and retailing have produced in this region, as elsewhere, fewer and larger farms, mechanized production requiring less labor, and a steady migration of farm and small-town people to the cities within and beyond the region. Family cars and trucks only permit the heavier concentration of services in a sparser network of towns spaced at ever greater driving distances away.

This fourth period of urban life in the Great Plains has produced, then, an intractable implosion of the region's urban pattern. Generations of investment in town buildings, streets, plantings, special facilities (most forlornly, the schools) lie bleaching under the open prairie skies in numberless towns too small to hold their populations. By the end of the twentieth century, very few towns under 15,000 inhabitants showed any ability to grow, and only cities at the geographical margins or with specific and solid functions such as in government, education, or health seem able to keep pace with national norms. The result is a scramble among the region's cities to chase growth for its own sake, competing within the national urban system for business investments at the risk of their tax base, while midsize cities soak up the small-town migrants discouraged by job losses and limited economic and social horizons in the small towns of their birth. The region is urbanizing at an unprecedented rate (given the ratio of city dwellers to rural residents) while losing the vast majority of its once-urban places. No other region in North America is undergoing quite this transformation. Since midcentury the Plains has been experiencing the "hollowest" era of its urban history, but it may also be qualitatively the best.

The Origins of Individual Urban Places

It is a commonplace to characterize urban life in the Great Plains almost exclusively on the basis of its small towns and to speak of the huge sameness among them as if they differed no more from each other than one generic strip mall from the next. The first tendency likely derives from the fringe position of most of the region's bona fide large cities. Denver is, after all, no more the metropolis of the High Plains portion of eastern Colorado than it is the capital of mountainous western Colorado. Kansas City also serves two regions of different economy and culture. The region's large cities seem more simply members of the national urban system, more preoccupied with global positioning than with representing the interests of their nearby Plains hinterlands, so the "Plains country town" does sterling duty as the "default" urban symbol for the region. But even if this is so, the standard image is misleadingly simplistic. Not all Plains cities and towns were platted by railroad tycoons, milked for their income, and cast to the winds when no longer useful.

A few Plains urban locations can trace their essential locations to early trading posts in the fur trade and forts guarding western trails, and to this day their proximity to water and to suitable crossing points for wheeled tra.c explains more fully their specific siting than any subsequent feature. Winnipeg, Manitoba; Edmonton, Alberta; Pierre, South Dakota; Fort Benton, Montana; and Leavenworth, Kansas, serve as ready examples. To these can be added a number of river towns sited as suitable places for emigrant provisioning and agricultural trade such as Atchison, Lawrence, and Topeka, Kansas. This type is distinguished by huge urban plats designed for speculative land sales and boosterism, and it prefigured those of the railroad era. But even before the railroad arived, spreading agricultural settlement stimulated the creation of "inland towns" (i.e., located away from navigable rivers), vast numbers of which failed to survive, but a goodly number that did, such as Bottineau and Cando, North Dakota, invariably did so by attracting a railroad.

Union Pacific Railroad depot (built 1886), looking west, Cheyenne, Wyoming

View largerThe railroads greatly augmented the frequency and density of speculative railroad towns on the Plains. Some independent townsite promoters thought it was sufficient to announce the mere existence of town plats on their land, but this rarely su.ced to attract settlers and generally dissuaded railroads. Promotion was most successful when undertaken by the railroads themselves, for they controlled both local land sales and connection with the wider world. The key to understanding the relation of speculative towns to the railroad is the alignment of railroad tracks within the plats; by definition, a railroad town is one wholly oriented to the axis of the rails, with its linear "railroad reserve." All other plan patterns denote some more complicated history of town and railroad.

Two other types of town origin loom large in the Great Plains. Towns founded as county seats declare this fact through the designation of a public square reserved for the county courthouse. Many actual county-seat towns lack such features because they were founded without such ambition, and numerous country towns contain such squares even though political history was not to bless them with the hoped-for prize. Presence and absence of such prominent elements in the built form of Plains towns echo the history of such aspirations and the geographical pattern of their outcome. In most cases, the primacy of commerce relegated the courthouse square to a peripheral position within the town plan.

Last among the key types of town origins are mining and oil towns. Here the striking features are the often-chaotic patterns produced by boom conditions, especially when aided by restricted sites, such as in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Awkward topography and rapid, unplanned growth have given places like Deadwood and Lead quite singular curving and terraced townscapes. Often, mining settlements were strictly company towns, though such origins did not always guarantee regular plans and coherent development.

Despite the diversity of urban origins, however, their initial distinctions have often barely endured, if at all. Subsequent development has had a way of generalizing if not standardizing the layout and built form as well as the social composition and community dynamics of many Plains towns. This has produced a high degree of geographical homogeneity among them, regardless of function or size, and has encouraged the emergence of a strong urban stereotype of the small town on the Plains.

Urban Roles and Town-Country Relations

This stereotype of the Plains small town transcends population size, although a town's size clearly betrays the accumulation of functions that it performs within the region's urban network. The largest cities on the Plains are the entrepôt towns, "gateway" cities that not only act as bulking and processing centers for crops and livestock raised on the Plains for onward shipment to distant markets in the East but also handle through traffic. One cannot stand on the street bridges that pass over the railroad yards in Cheyenne, Wyoming, and Fargo, North Dakota, and fail to appreciate that the Great Plains is a vast transit region, a geographical obstacle to freight passing across the continent from end to end. Such traffic is almost irrelevant to the region, except that its maintenance provides some local jobs. But these gateway cities are more than entrepots: they are also hubs for people and goods originating and terminating somewhere not too far away on the Plains; most strikingly, now they are portals for air travel.

The purpose of towns and cities on the Plains has always been primarily to organize the export of crops, livestock, and minerals from the region. This necessitates a mostly dispersed rural population to produce the materials and supply centers to provide the essentials of life to that dispersed population. Hence, "shipping" is the key function of all such places, regardless of scale. Location on the transportation arteries of this system has always been the essence of their success, first and last via the railroad system, from the first boisterous frontier cow towns to the prosaic farm or ranch towns of today.

The smallest shipping points represent towns–one can hardly call them that–with a couple of grain elevators, a repair garage perhaps, and a hundred or so residents. Farther up the size scale are towns that can still boast a grocery store, gas station, maybe a bank, and some other businesses and support a population of several hundred. Beyond this, there is one standard function that boosts such towns into another league: a few hundred towns have county-seat status. Serving as centers of county government provides work for a small host of professionals, including engineers, lawyers, accountants, politicians, and office workers whose combined income supports a thousand residents or more and a correspondingly wider range of stores and other social services. Often, county towns contain courthouses with eye-catching classical or modern architecture: the higher the Plains (i.e., the more westerly the location), the lower the pretension. With just these three lower rungs of the Great Plains urban hierarchy, we have accounted for the vast majority of urban places in the whole region.

County courthouse and surrounding business district, Weatherford, Texas

View largerBetween the small service centers and the gateway cities, the hierarchy supports a few medium-size cities that derive their importance from special functions. These are the state capitals, college towns, and mineral towns that dot the region with a casual regularity. Only five capitals of the ten states with territory in the Great Plains are situated well within the Plains proper. Colleges, particularly public institutions, share with other state facilities such as prisons and medical centers the historical function of ensuring the permanent decentralization of state expenditures. Only the mineral towns, whether mining gold or pumping oil, obey geology and cluster where the deposits have been found, in the Black Hills of South Dakota or the gas and oil fields of the Permian Basin. The size and facilities of all these places with special functions create a different local culture, sometimes more cosmopolitan, sometimes even more tenuous than that of farm and ranch urbanism. Midland, Texas, for example, headquarters of Permian Basin oil power, was obliged to promote itself as a retirement town and convention center due to the decline of oil prices after 1986 and the subsequent contraction of the industry. The future of Lead, South Dakota, is even more precarious, following the announcement in 2000 that its renowned Homestake Gold Mine was phasing out operations.

What is strikingly absent from the Plains, however, is large-scale urban manufacturing. Early city boosters may have hoped for the expansion of the national manufacturing belt into the region, but its remoteness from the majority of the nation's urban demand guaranteed that it would never really develop heavy industry. Pueblo, Colorado, has had a steel industry since the 1880s, but this is an exception (and even there employment has fallen from more than 9,000 in the 1950s to fewer than 700 in 2000). Manufacturing logic has always placed most final-stage processing and fabrication close to the markets rather than the raw materials. While meatpacking decentralized westward onto the Plains during the twentieth century, attracting especially Latino workers, it does not pack the economic punch of car plants or steelmaking.

People Attracted to Great Plains Towns

Plains towns, like their surrounding rural areas, acquired their early populations from three distinct sources: Indigenous peoples, native-born migrants from the East and Midwest moving farther west, and foreign-born immigrants arriving especially from northern and eastern Europe. Long-established ethnic groups have contributed significant populations to local towns in areas where they have been well represented, such as Native Americans in eastern Montana, North and South Dakota, and Oklahoma, Hispanics in northeastern New Mexico, West Texas, and southeastern Colorado, and African Americans in eastern Oklahoma. American migrants from states to the east have maintained broad though somewhat mixed zones of latitudinal movement, so that settlers of eastern and central Canada, New England, and upper Midwest heritage were more likely to settle on the Northern Plains, those of "North Midland" origin on the Central Plains, and those from the South on the Southern Plains. Into this mixture, Europeans came in large numbers, filling up the open frontier especially in the Prairie Provinces and the Dakotas but also localities farther south, often in response to vigorous promotional efforts.

The "latitudinal" transfer of population to the Canadian Prairies a century ago from Ontario and points east was even more pronounced than south of the border precisely because of the linear structure of Canada's human geography. This was especially so for the English-speaking Canadian and British migrants, who, because of advantages of language and petty capital, could often form a wide and deep small business class that populated the towns of all sizes across the region. Nevertheless, this western border was non-ideological and porous, and many settlers of British, Canadian, American, and continental European stock drifted easily back and forth between American Plains and Canadian Prairies.

Over time, there have been subtle shifts in the social composition of Plains towns. Early on, Canadian and American migrants often made up the bulk of the small merchant class because they brought trading experience and some capital to the frontier towns. Slowly, as young country people moved to town, the business class broadened its ethnic complexion, while retired farmers from strongly ethnic country communities added further to the social diversity of the towns. Suggestive is the proportion of businessmen of Norwegian to Anglo stock in three North Dakota counties with strong Norwegian representation, judged by the ethnicity of advertisers in county atlases in the early twentieth century. The Grand Forks County atlas of 1909 contains the names of ninety Anglo businessmen to fifty-three of Norwegian stock, and the McHenry County atlas of 1910 shows forty-seven of Anglo background and thirty of Norwegian stock. By 1929, however, the Bottineau County atlas was listing only thirty-eight Anglo businessmen to seventy-six of Norwegian extraction. Crude though these comparisons are, they lend some credence to the notion that Plains towns gradually extended participation to the would-be entrepreneurs of their hinterlands. Such opportunities often provided staging points for family members to migrate farther up the regional and national urban ladder.

Three Plains Urban Archetypes

The comparative diversity of urban roles performed by towns on the Plains might suggest any number of "typical" towns for the region. The dominating image of the "plains country town," on the other hand, works hard against that. What follows is an attempt to recognize at least a trinity of typical Plains towns, the better to capture some of the diversity already noted while concentrating on characteristics readily apparent to anyone with an attentive eye. Although they are selective, these types–the gateway city, the plains country town, and the ethnic town–exist clearly in the landscape.

THE GATEWAY CITY

It is virtually impossible to approach the Great Plains from either east or west by train today (using what is left of the fabled passenger rail network of bygone days) without passing through one of the region's gateway cities. Even using superhighways, one enters the region by skirting the edges of one or another of these great entrepôts. They have preserved, indeed enhanced, their historic regional roles while adding new ones pertinent to the information age. What do these gateway cities look like, how are they laid out, and what are their distinctive features?

However much the central skyline of the gateway city center resembles that of all other self-respecting American downtowns, with its tall office buildings and hotels, its ring of parking lots, and the awkward architectural remains of a once-thriving shopping district, what typifies the gateway city is the scale and land-use dominance of freight-handling facilities and warehouse districts. Most gateway centers have modernized their transportation zones, placing them recurrently on or near the urban fringe to gain the space for the vast operations needed. These outlying districts are impressive enough, but the long history of transfer functions can be found even closer to hand, in the near-central railroad depots and brick warehouse districts that still lurk near the old downtown, now often transformed into funky entertainment districts for tourists and locals alike. Many such districts have lost numerous structures, victims of bulldozer redevelopment before old brick became fashionable. But the remaining warehouse quarters of cities such as Omaha, Denver, Fort Worth, Fargo, Cheyenne, and Billings, to name a few, stand as testimony to the specialized role these places have long played in the national system of cities.

The wholesale warehouse districts have always been tied to the railroads, and even today, with the importance of truck shipments and intermodal transport, that link survives intact. Winnipeg boasts a great array of railroad yards and transfer facilities, far more extensive than in most other cities of its population size.

Gateway cities that collect the produce of the corn and wheat belts also sport impressive stands of grain elevators, not just the two or three silos of the country shipping point but huge regiments of cylindrical concrete towers, taller than any office block in town, that march across and blot out the horizon, as in Atchison, Kansas, and Enid, Oklahoma. Gateway towns opposite ranching areas used to boast massive stockyards, such as at Fort Worth and Omaha, but they are now victims of a westward decentralization of slaughtering. Even here, however, the cultural heritage of such facilities lives on in the urban folk life of such places, sustained by the nostalgia of country and western music or perhaps a famed steakhouse.

Not only the physical equipment of railroad and truck transshipment distinguishes these cities but also their historical occupational profiles and still distinctive business and political cultures, with hotels catering to visitors to the cities' wheat exchanges and stockmen's clubs, where deals still get made. In a world of corporate globalism, more of the action is taking place elsewhere, but the original purposes of these gateway cities have yet to be wholly eclipsed. Many have begun to market their special character for tourists, even at the risk of bowdlerization. But theatrics apart, what remains undisputable about the Plains gateway city is its long involvement in transport, transfer, and storage and its geographical function as the eye of the needle through which all the produce of the Plains is threaded on its way to distant processing and divided profit. The Plains gateway cities are large enough each to have a peculiar morphology, but, at base, the essential features are common to all of their class.

THE PLAINS COUNTRY TOWN

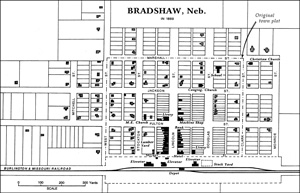

Bradshaw, Nebraska, 1889

View largerThe scale of the Plains country town is personal. It is, in its archetypal form, small enough to be walked through from end to end in a few minutes. It is also virtually predictable in its contents and layout. Whether a "parallel" town, a "T-town" (referring to the axes of railroad reserve and commercial core), or a fusion of the two patterns, the Plains country town is like some outsize combination of a child's erector set, wooden play blocks, and model train layout. Invariably stamped on the prairie as if with a cookie cutter by a railroad department or a speculative land company and named after the railroad's owner or other such chance association, the town pays almost total obeisance to the railroad tracks.

The genre can be encapsulated in its essentials by the case of Bradshaw, Nebraska, in 1889. Founded in 1879 by the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad Company, the town site had a population of 150 residents the very next year. Created to serve the farmers of western York County, about fifty-five miles west of Lincoln, Bradshaw in 1889 offered three grain elevators along the tracks, together with the train depot and a small stockyard. Railway Street ran like a cordon along the railroad reserve, from which sprang Lincoln Street, the business thoroughfare–all one and a half blocks of it. There was a lumberyard, a hotel, a bank, two liveries, thirty business buildings, three churches, a school, and eighty-nine residences. Strikingly, while the business district was compact, reflecting the importance for merchants of proximity to the railroad and other businesses, the town's residential space was loose. After only ten years of life and with 112 empty building lots still available in the "Original Town," landowners felt it essential to plat four "additions," more than doubling the lotted area of the town. Forty-one residences lolled over this additional territory, their owners quite unable to contemplate settling on the still vacant land of the Original Town.

Such was the planning and early development history of Bradshaw. Vary the orientation by which the tracks pass through the locality, shift the street alignments accordingly so that they meet at some angle, but no matter what adjustments are made, this is the physical blueprint for tens of thousands of "towns" planted upon the soil of the Great Plains. As speculations, their future was subject to the fortunes of remote markets, railroad politics, and sometimes chicanery, and thousands failed almost before they had started. Importantly, though, here was a model plan, infinitely expandable should the town succeed, simple, orderly, but allowing for the disorder of individual choice, and a perfect mechanism for transferring the risks of urban growth to the shoulders of optimistic settlers while relieving them of a sizable chunk of their initial capital. Town boosting had long become a high art in American life by the time the Plains were settled, and its exquisite delineation on the ground can be found right here. Bradshaw in 1889, even in its elegant simplicity, was a cipher for all the utilitarian philosophy of urbanism that played itself out like a hapless tide across the Great Plains.

THE ETHNIC TOWN

The ethnic town or, more often, village is the third recurrent urban archetype of the Great Plains. Consistent with the small scale of most "urban" places on the Plains, many small urban centers have emerged and even survived as de facto ethnic towns, representative of the high concentration of ethnic settlement in the surrounding countryside, sometimes even remaining virtually exclusive to one group. The larger cities have developed their varied neighborhoods of immigrant complexion, from Calgary to Kansas City, but these seem little different from those of big cities all over the nation. It is precisely on the Plains proper, where the relative recency of concentrated ethnic settlement has preserved a sharper ethnic imprint on the landscape than in most older sections of the two countries, that one can find still viable, if not always vibrant, ethnic towns. Their comparative isolation favored slower national integration, and some groups have resisted assimilation through various habits and attitudes, hence the survival to this day of numerous small but stubbornly distinctive and self-conscious ethnic enclaves throughout the Great Plains.

The Canadian Prairies and the Northern Plains of the United States stand out in this respect, given their availability for settlement during the last great tides of agrarian immigration from central, eastern, and northern Europe around the turn of the twentieth century. From the Ukrainian, German, Scandinavian, and French Canadian tracts around Edmonton to the Doukhobor districts north of Saskatoon and the French Canadian and Mennonite settlements in the southern and western hinterlands of Winnipeg, small urban centers with names like Wostok, St. Alphonse, and Halbstadt dot the western Canadian landscape. In their churches and ethnic business names, if not always in other features, they display their ethnic affiliation, indeed, their urban purpose. Farther south, the pattern is repeated from North Dakota to central Kansas and even in Oklahoma and Texas. Few travelers can fail to observe the Native American characteristics of towns serving Indian populations in Oklahoma such as Okmulgee, where the old Creek Council House graces the courthouse square, or Tahlequah, where street signs are bilingual. Likewise, the cultural character of the Volga German communities of Ellis County, Kansas, finds expression in the unexpected and strikingly tall Catholic church steeples of Pfeifer, Liebenthal, St. Catharine, and, most dramatically, the "Cathedral of the Plains" at Victoria (Herzog).

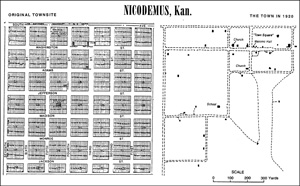

Nicodemus, Kansas

View largerNicodemus, Kansas, stands as a celebrated all-black town settled by "Exodusters" in 1877. Founded as a speculative town site to attract blacks from the South, it was paired as a business enterprise with Hill City, a town twelve miles to the west in Graham County intended for white settlers. Twelve years later, the Union Pacific Railroad bypassed Nicodemus and connected Hill City, which consequently became the county seat. Thereafter, Nicodemus stagnated, losing most of its businesses to nearby Bogue and to Hill City. Notable are Nicodemus's long but narrow town lots, which measure 25 by 160 feet. The modal urban lot width in the Great Plains is closer to 50 feet. While Hill City also has 25-foot-wide lots, the early town plan there included city blocks reserved for a school and a courthouse, amenities lacking in the Nicodemus plan, the purest expression of monetized land. While Nicodemus never filled up the plat, it hung on as a social center for the surrounding African American farming community and in 1976 was designated a national historic landmark for its significance in interpreting the nation's cultural heritage. To this day, Emancipation Day is celebrated on the informal "town square."

City Building and Urban Culture

The progress of American urbanism in the Great Plains is measured for the most part in the diffusion of amenities, technical accomplishments, and stylistic fashions over time from the largest trendsetting metropolises of the nation–New York, Chicago, St. Louis, and their ilk–to the gateway cities and medium-size centers of the region. It is hardly to be expected that great new urban innovations would emanate from the modest cities of the Plains. Nevertheless, Plains urbanism was developed in the late nineteenth century by the most routinized and relentless booster program up to that period. Because the Great Plains was so vast and seemingly so underdeveloped, boosting was particularly required in order to steer capital into the region and attract settlers.

In some ways, Plains urban centers were designed and built with "cutting-edge" concepts on a tabula rasa. Even today, commercial districts and residential sections reflect the new norms of building technology, design, and furnishings current during the period from the 1890s through the 1920s. Since the first wooden merchant structures lasted at least a few years, most of the more substantial buildings that replaced them came in the twentieth century. Where high-rise business structures were built, they sported the new wide, Chicago-style windows that let in light rather than the narrow, New York–influenced vertical windows long popular in the East. Residences featured the latest in standard manufactured design, and Plains towns must account for a disproportionate national share of the mail-order homes shipped by Sears, Roebuck and Company and its competitors.

Occasionally, Plains cities claimed national attention for some avant-garde creation, which is best illustrated in the case of two state capitols. By 1918 Nebraska's capitol was deemed insu.cient, and, following a national competition won by Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, in 1922 construction began on the present mini-dome-capped skyscraper edifice, with Art Deco decoration produced by local artists. North Dakota followed in 1931, when fire destroyed the existing traditional capitol, opting for a spartan, slablike office high-rise building designed by a consortium of local and Chicago architects. Such choices reflect the ethos of modernity that was permeating the Plains in the early twentieth century and a certain rejection of unnecessary frills in favor of functionalism. By and large, however, such banner projects found few echoes in the private sector, and on the residential front, most urban neighborhoods, of whatever social class, have tended to exude a comfortable, traditional normality of external appearance while displaying internal modernity in proportion to economic capacity. Much of this stems from the relative homogeneity of income in Plains towns, where the extremes of urban wealth generated by high industrialism have generally been absent or muted. Only the banker's house, the doctor's house, and the funeral home stand out as conspicuous ornaments in many a Plains country town. And only rarely does a public building seek to astound, as the Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota, in a folksy way surely does.

In public infrastructure, Plains cities have performed close to the national average for their size. A late start in city building for most towns meant that the thresholds of population needed to capitalize services such as electric power plants, street railways, telephones, and modern hospitals kept these places from being precocious centers of innovation. But in terms of their own development, many such services came sooner in the experience of residents than they had in older cities. Street railways are a good indicator: while Plains cities were not innovators in this realm, they adopted the technology with eagerness. Street railways came early in the individual history of Plains towns because their fast initial growth promised the patronage needed to sustain the railways. Installations were so numerous in towns below 5,000 population, however, that many failed and caused the towns to wait a number of years before reinstallation was successful. In other respects, urban centers on the Plains generally attempted to participate in urbanistic novelties in proportion to their size and enterprise. Most cities of any size, for example, display some of the boulevards and curving drives so fashionable in the trendsetting metropolises of the East and Far West, even if on a modest or token scale.

Generalizations

Risking dispute through inevitable selectivity, several generalizations about urbanism in the Great Plains might be proposed here. First, the past is still young in Plains towns and cities, and it is not very important while economic growth is apparent. The past becomes more important when growth subsides and economic stress increases, because it offers a validation of prior accomplishments and a means to recapitalize the built environment through historic preservation and tourist edification. Some of the striking public sculpture to be found in some Plains towns featuring heroic ox teams plowing the prairies (in Fargo, North Dakota) or cowboys herding steers (Billings, Montana, and Dodge City, Kansas) now seeks to develop this urban theme.

Second, in county seats on the Plains, government functions are generally secondary to commercial ones, so it is very rare, in contrast to such places in older sections of the nation, to find the courthouse square the central focus of the town; rather, it is the railroad and its shipping facilities that define the town and attract the business district, leaving the civil government precinct well off to the side in the town plat.

Third, the size and variety of urban equipment in the Great Plains is inversely proportional to altitude. Generally, the farther west towns are located, the more limited are the size, number, and architectural pretension of their business buildings and government installations. In western North Dakota, for example, some county courthouses in exterior appearance are almost indistinguishable from neighboring real estate agencies and grocery stores. In the western Canadian north–south corridor from Edmonton to Lethbridge, however, many quite pretentious public buildings stand in contrast to this rule.

Fourth, the formal urban threshold is set comparatively low in the Great Plains, and for historical reasons. Incorporation laws in several Plains states, for example, permit places to be regarded as "cities" at population levels far below the national norm. Kansas provides the most extreme case, allowing settlements of as small as 300 inhabitants to incorporate as cities. Elsewhere in the modern world, such places would be considered mere hamlets or villages. Indeed, even in Kansas they are usually that, despite their legal status.

Fifth, many rim cities and state and provincial capitals are prominent in service functions such as health facilities, insurance companies, and educational campuses, drawing from sometimes-enormous tributary areas. Billings, Montana, offers hospital facilities that would scarcely be found in cities of comparable size in, say, Illinois, because distances on the Plains are so large and such cities few and far between. Conversely, and sixth, transshipment and wholesale activities are more significant than manufacturing. This imbalance suggests the extent to which Plains urban centers are more dependent on the outside world than those in denser settled regions, a characteristic once shared with the traditional South but no longer.

Seventh, all cities and towns actually on the Plains are close to the countryside, in a mental sense, through their intimate economic ties and the remoteness of sophisticated urban distractions. A broadly engendered "small-town mentalité" exists even in the larger centers, reinforced by migration patterns from the rural areas and knowledge of their rural constituencies' demands for cultural inspiration.

Lastly, Great Plains urbanism is a kind of derivative and dependent urbanism. There is comparatively little that was, or is, original, self-sustaining, or generative about urban life in the Great Plains. In terms of the two nation-states across which the Great Plains extend, their urban landscapes reflect classically those of internal colonization. Nevertheless, they represent an extraordinary production of urban life across a vast land.

See also AFRICAN AMERICANS: Exodusters / ARCHITECTURE: Grain Elevators; Nebraska State Capitol; Public Buildings; Warehouse Districts / EUROPEAN AMERICANS: Settlement Patterns, Canada; Settlement Patterns, United States / IMAGES AND ICONS: Corn Palace; Deadwood, South Dakota / PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT: Palliser's Triangle / TRANSPORTATION: Railroads, United States; Railways, Canada.

Michael P. Conzen University of Chicago

Artibise, Alan F., ed. Town and City: Aspects of Western Canadian Urban Development. Regina: University of Regina, Canadian Plains Research Center, 1981.

Bennett, John W., and Seena B. Kohl. Settling the Canadian-American West, 1890–1915: Pioneer Adaptation and Community Building: An Anthropological History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Hamilton, Kenneth Marvin. Black Towns and Profit: Promotion and Development in the Trans-Appalachian West, 1877–1915. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991.

Haywood, C. Robert. Victorian West: Class and Culture in Kansas Cattle Towns. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1991.

Hudson, John C. Plains Country Towns. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985.

Melnyk, Bryan P. Calgary Builds: The Emergence of an Urban Landscape, 1905–1914. Calgary: Alberta Culture, Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1985.

Mothershead, Harmon. "River Town Rivalry for the Overland Trade." Overland Journal 7 (1989): 14–23.

Nelson, Paula M. After the West Was Won: Homesteaders and Townbuilders in Western South Dakota, 1900–1917. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1986.

Reps, John W. Cities of the American West: A History of Frontier Urban Planning. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979.

Schellenberg, James A. Conflict between Communities: American County Seat Wars. New York: Paragon House, 1987.

Stock, Catherine McNicol. Main Street in Crisis: The Great Depression and the Old Middle Class on the Northern Plains. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Tauxe, Caroline S. Farms, Mines, and Main Streets: Uneven Development in a Dakota County. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993.

Toms, Donald D. The Flavor of Lead: An Ethnic History. Lead SD: Lead Historic Preservation Commission, 1992.

West, Carroll Van. Capitalism on the Frontier: Billings and the Yellowstone Valley in the Nineteenth Century. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

Wetherell, Donald G., and Irene R. A. Kmet. Town Life: Main Street and the Evolution of Small Town Alberta. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1995.

XML: egp.ct.001.xml